Chapter Introduction

2

Books and the Power of Print

Since its 1994 founding, Amazon has grown from a scrappy upstart to the leading Internet bookseller to a vast online retailer selling not just media but clothing, household items, and hardware—including its Kindle, the first e-reader to achieve real commercial success and a nod to its origins as a bookstore. Today, Amazon is the largest seller of e-books and printed books, easily accounting for over 40 percent of sales in the United States.1 The Web site’s easy-to-use 1-Click and Pre-order buttons, along with quick shipping options, make buying convenient for consumers and help books sell—that is, as long as Amazon is not fighting with the book’s publisher.

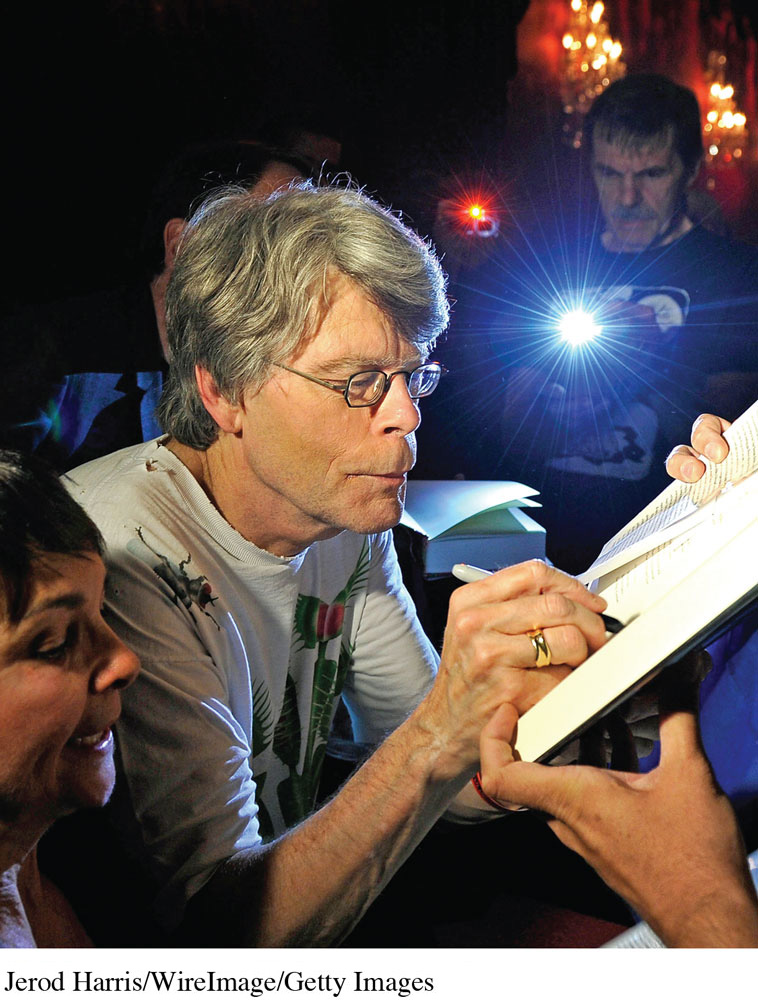

In 2014, the 1-Click and Pre-order buttons disappeared from the pages advertising certain books, and delivery times for shipping some books mysteriously jumped from a few days to a few weeks. Far from accidental, these changes affected only those books published by Hachette—one of the world’s largest publishing companies—because of a contract dispute with Amazon.2 The dispute generated national headlines, with high-profile authors like David Baldacci, Nora Roberts, and Stephen King (shown signing books for fans in the photo to the left) calling for a quick resolution that would be fair to authors who were suffering as a result of Amazon’s making book purchases from Hachette less convenient (a big deal for an Internet business model built around customer convenience). Although not all details were made public, key issues seemed to involve pricing and how much Hachette would have to pay for promotion on Amazon’s Web site. One high-profile author caught in the crossfire was J.K. Rowling of Harry Potter fame, whose new book under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith couldn’t be pre-ordered on the Amazon site.3 Not all authors have sided with Hachette; although some critics worry that Amazon’s rapid growth has hurt writers as well as independent bookstores, some low-profile authors have praised Amazon for allowing independent writers greater opportunities to publish digitally, sidestepping traditional publishing houses.

The two sides reached an agreement in mid-November 2014, returning Hachette titles to “normal availability” just in time for the annual holiday shopping season. Few details of the agreement have been made public, but part of the deal appears to allow Hachette to set e-book prices on Amazon, with incentives to offer discounts. And although there is a degree of relief among authors, one group of authors is still concerned about Amazon’s position in the bookselling marketplace and says it intends to ask the U.S. Department of Justice to review Amazon’s business practices.4

Although important for authors and publishers, the deal with Hachette (and an earlier deal with Simon & Schuster) might not be as noticeable to consumers as another recent Amazon announcement. Amazon says its new Kindle Unlimited service offers more than 700,000 books and audio books for reading and listening for a set monthly fee (about ten dollars), similar to the model used by Netflix for video content.5 This announcement raises questions about how the smaller companies, like Oyster and Scribd, that already offer all-you-can-read subscriptions for a monthly fee will be able to compete with the powerful retail behemoth.

Whether discussing a handful of big publishing houses or a single giant retailer, many familiar with the publishing industry worry about how too few powerful interests might abuse their ability to decide which books will get published and promoted. Will there be too much temptation for these powerful interests along political or ideological lines? Will the emerging publishing business model mean the quiet death of important but commercially risky books? As the next few pages will explain, the history of books is also the history of mankind’s most important ideas. As such, the battles in book publishing about costs, prices, and contracts are also about the free flow of ideas—and our access to them.

FOR HUNDREDS OF YEARS—before newspapers, radio, and film, let alone television and the Internet—books were the only mass medium. Books have fueled major developments throughout human history, from revolutions and the rise of democracies to new forms of art (including poetry and fiction) and the spread of religions. When cheaper printing technologies laid the groundwork for books to become more widely available and more quickly disseminated, people gained access to knowledge and ideas that were previously reserved for only the privileged few.

With the emergence of new types of mass media, some critics claimed that books would cease to exist. So far, however, that’s not happening. In 1950, U.S. publishers introduced more than 11,000 new book titles; by 2007, that number had reached more than 190,000 (see Table 2.1). Though books have adapted to technology and cultural change (witness the advent of e-books), our oldest mass medium still plays a large role in our lives. Books remain the primary repository of history and everyday experience, passing along stories, knowledge, and wisdom from generation to generation.

In this chapter, we will trace the history of this enduring medium and examine its impact on our lives today by:

assessing books’ early roots—including the inventions of papyrus (the first writing surface) and the printing press, as well as the birth of the publishing industry in colonial America

exploring the unique characteristics of modern publishing, such as how publishing houses are structured

taking stock of the many types of books that are available today, from the variety of print books to both electronic and digital books

examining the economics of the book industry, including how players in the industry make money, and what they spend it on to fulfill their mission

considering the role of books in our democracy today, as this mass medium confronts several challenges