The Early History of Books: From Papyrus to Paperbacks

Books have traveled a unique path in their journey to mass medium status. They developed out of early innovations, including papyrus (scrolls made from plant reeds), parchment (treated animal skin), and codex (sheets of parchment sewn together along the edge and then bound and covered). They then entered an entrepreneurial stage, during which people explored new ways of clarifying or illustrating text and experimented with printing techniques, such as block printing, movable type, and the printing press. The invention of the printing press set the stage for books to become a mass medium, complete with the rise of a new industry: publishing.

Papyrus, Parchment, and Codex: The Development Stage of Books

The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, and Romans all produced innovations that led up to what looked roughly like what we today think of as a book. It all began some five thousand years ago, in ancient Sumeria (Mesopotamia) and Egypt, where people first experimented with pictorial symbols called hieroglyphics or early alphabets. Initially, this writing was placed on wood strips or stones, or pressed into clay tablets. Eventually, these objects were tied or stacked together to form the first “books.” Around 1000 BCE, the Chinese were using strips of wood and bamboo with writing on them, tied together to make a booklike object.

Then, in 2400 BCE, the Egyptians began turning plants found along the Nile River into a material they could write on called papyrus (from which the word paper is derived). Between 650 and 300 BCE, the Greeks and Romans adopted the use of papyrus scrolls. Gradually, parchment—treated animal skin—replaced papyrus in Europe. Parchment was stronger, smoother, more durable, and less expensive than papyrus. Around 105 CE, the Chinese began making paper from cotton and linen, though paper did not replace parchment in Europe until the thirteenth century.

The first protomodern book was most likely produced in the fourth century by the Romans, who created the codex—sheets of parchment sewn together along one edge, then bound with thin pieces of wood and covered with leather. Whereas scrolls had to be rolled and unrolled for use, a codex could be opened to any page, and people could write on both sides of a page.

| Year | Number of Titles |

|---|---|

| 1778 | 461 |

| 1798 | 1,808 |

| 1880 | 2,076 |

| 1890 | 4,559 |

| 1900 | 6,356 |

| 1910 | 13,470 (peak until after World War II) |

| 1915 | 8,202 |

| 1919 | 5,714 (low point as a result of World War I) |

| 1925 | 8,173 |

| 1930 | 10,027 |

| 1935 | 8,766 (Great Depression) |

| 1940 | 11,328 |

| 1945 | 6,548 (World War II) |

| 1950 | 11,022 |

| 1960 | 15,012 |

| 1970 | 36,071 |

| 1980 | 42,377 |

| 1990 | 46,473 |

| 1996 | 68,175* |

| 2001 | 114,487 |

| 2004 | 164,020 |

| 2007 | 190,502* |

| 2011 | 177,126 |

*Changes in the Almanac’s methodology in 1997 and for the years 2004–2007 resulted in additional publications being assigned ISBNs and included in the count.

Data from: Figures through 1945 from John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United States, 4 vols. (New York: R. R. Bowker, 1972–81); figures after 1945 from various editions of the Library and Book Trade Almanac formerly The Bowker Annual (Information Today, Inc.) and Bowker press releases

Writing and Printing Innovations: Books Enter the Entrepreneurial Stage

Books entered the entrepreneurial stage with the emergence of manuscript culture. In this stage, new rules about written language and book design were codified—books were elaborately lettered, decorated, and bound by hand. Inventors also began experimenting with printing as an alternative to hand lettering and a way to speed up the production and binding of manuscript copies.

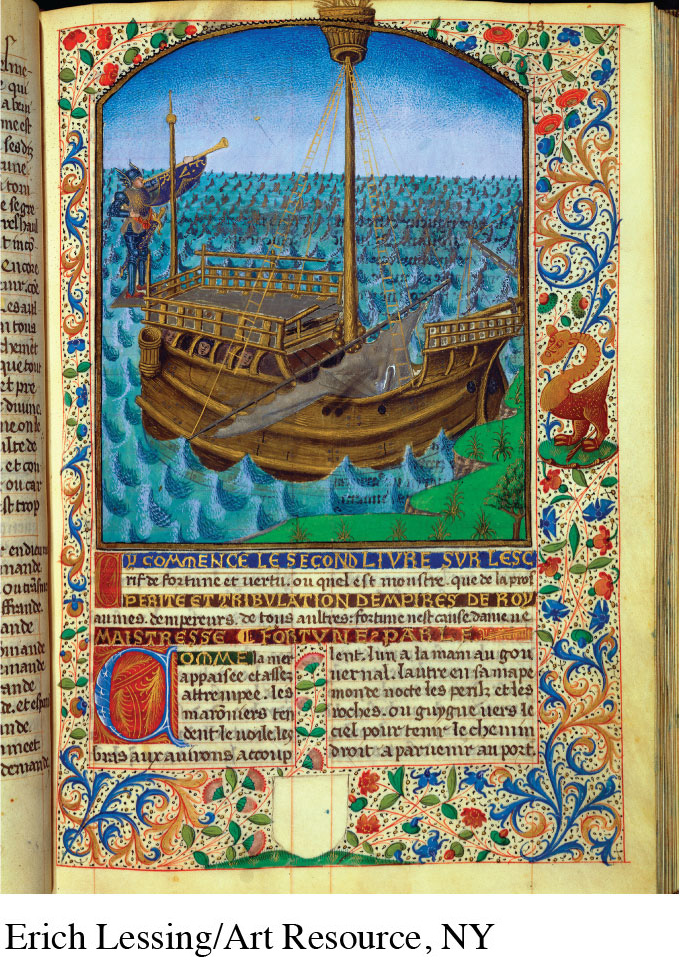

Manuscript Culture

During Europe’s Middle Ages (400 to 1500 CE), Christian priests and monks transcribed the philosophical tracts and religious texts of the period, especially versions of the Bible. These illuminated manuscripts featured decorative, colorful illustrations on each page and were often made for churches or wealthy clients. These early publishers developed certain standards for their works, creating rules of punctuation, making distinctions between small and capital letters, and leaving space between words to make reading easier. Some elements of this manuscript culture remain alive today in the form of design flourishes, such as the drop capitals occasionally used for the first letter in a book chapter.

Block Printing

If manuscript culture involved advances in written language and book design, it also involved hard work: Every manuscript was painstakingly copied one book at a time. From as early as the third century, Chinese printers came up with an innovation that made mass production possible.

These Chinese innovators developed block printing. Using this technique, printers applied sheets of paper to large blocks of inked wood into which they had hand-carved a page’s worth of characters and illustrations. The oldest dated block-printed book still in existence is China’s Diamond Sutra, a collection of Buddhist scriptures printed by Wang Chieh in 868 CE.

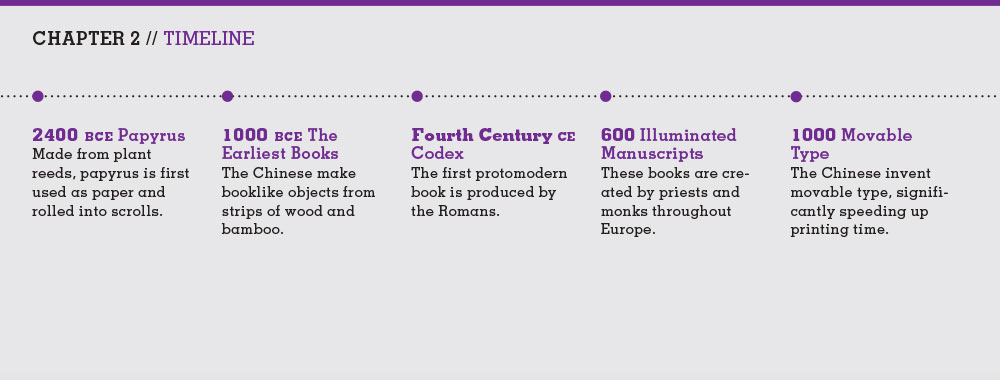

CHAPTER 2 // TIMELINE

2400 BCE Papyrus

Made from plant reeds, papyrus is first used as paper and rolled into scrolls.

1000BCE The Earliest Books

The Chinese make booklike objects from strips of wood and bamboo.

Fourth Century CE Codex

The first protomodern book is produced by the Romans.

600 Illuminated Manuscripts

These books are created by priests and monks throughout Europe.

1000 Movable Type

The Chinese invent movable type, significantly speeding up printing time.

1453 Printing Press

Gutenberg invents the printing press, forming the prototype for mass production.

1640 The First Colonial Book

Stephen Daye prints a collection of biblical psalms.

1751 Encyclopedias

French scholars begin compiling articles in alphabetical order.

1800s Publishing Houses

The book industry forms prestigious companies that produce and market works of respected writers.

1836 Textbooks

William H. McGuffey publishes the first in his series of Eclectic Readers, helping American students learn how to read.

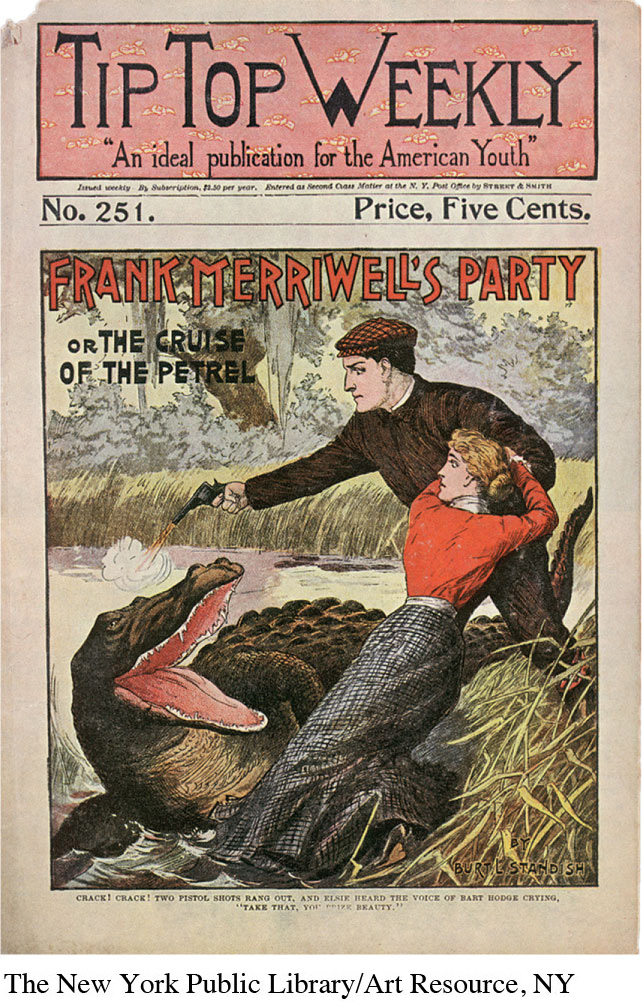

1870s Mass Market Paperbacks

Pulp-fiction paperbacks become popular among middle- and working-class readers.

Mid-1880s Linotype and Offset Lithography

New printing techniques lower the cost of books in the United States.

1926 Book Clubs

The Book-of-the-Month Club and the Literary Guild are formed.

1960s Professional Books

The book industry targets various occupational groups.

1971 Borders Is Established

The chain formation of superstores begins.

1995 Amazon.com

The first online book distributor is established.

2007 Harry Potter

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows has record-breaking sales of 13.1 million copies.

2007 Kindle

Amazon.com introduces the Kindle, the most successful e-book reader to date.

2011 Borders Closes

The chain files bankruptcy and the same year closes all of its stores, as brick-and-mortar stores lose business to digital sales.

2014 Hachette Dispute

Amazon fights publicly with Hachette over prices.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

Movable Type

The next significant step in printing came with the invention of movable type in China around the year 1000. This was a major improvement (in terms of speed) over block printing because, rather than carving each new page on one block, printers carved commonly used combinations of characters from the Chinese language into smaller, reusable wood (and later ceramic) blocks. They then put together the pieces needed to represent a desired page of text, inked the small blocks, and applied the sheets of paper. This method enabled them to create pages of text much more quickly than before.

The Printing Press and the Publishing Industry: Books Become a Mass Medium

Books moved from the entrepreneurial stage to mass medium status with the invention of the printing press (which made books widely available for the first time) and the rise of the publishing industry (which arose to satisfy people’s growing hunger for books).

The Printing Press

The printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Germany between 1453 and 1456. Drawing on the principles of movable type, and adding to them a device adapted from the design of a wine press, Gutenberg’s staff of printers produced the first so-called modern books, including two hundred copies of a Latin Bible—twenty-one of which still exist. The Gutenberg Bible (as it’s now known) was printed on a fine calfskin-based parchment called vellum.

Printing presses spread rapidly across Europe in the late 1400s and early 1500s. Many of these early books were large, elaborate, and expensive. But printers gradually reduced the size of books and developed less-expensive grades of paper. These changes made books cheaper to produce, so printers could sell them for less, making the books affordable to many more people.

The spread of printing presses and books sparked a major change in the way people learned. Previously, people followed the traditions and ideas framed by local authorities—the ruling class, clergy, and community leaders. But as books became more broadly available, people gained access to knowledge and viewpoints far beyond their immediate surroundings and familiar authorities, leading some of them to begin challenging the traditional wisdom and customs of their tribes and leaders.6 This interest in debating ideas would ultimately encourage the rise of democratic societies in which all citizens had a voice.

The Publishing Industry

In the two centuries following the invention of the printing press, publishing—the establishment of printing shops to serve the public’s growing demand for books—took off in Europe, eventually spreading to England and finally to the American colonies. In the late 1630s, English locksmith Stephen Daye set up the first colonial print shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts. By the mid-1760s, all thirteen colonies had printing shops. Some publishers, such as Benjamin Franklin, grew quite wealthy in this profession.

However, in the early 1800s, U.S. publishers had to find ways to lower the cost of producing books to meet the exploding demand. By the 1830s, machine-made paper replaced the more expensive handmade varieties, cloth covers supplanted costlier leather ones, and paperback books were made with cheaper paper covers (introduced in Europe), all of which helped to make books even more accessible to the masses. Further reducing the cost of books, publishers introduced paperback dime novels (so called because they sold for five or ten cents) in 1860. By 1885, one-third of all books published in the United States consisted of popular paperbacks and pulp fiction (a reference to the cheap, machine-made pulp paper dime novels were printed on).

Meanwhile, the printing process itself also advanced. In the 1880s, the introduction of linotype machines enabled printers to save time by setting type mechanically using a typewriter-style keyboard. The introduction of steam-powered and high-speed rotary presses also permitted the production of even more books at lower costs. With the development of offset lithography in the early 1900s, publishers could print books from photographic plates rather than from metal casts. This greatly reduced the cost of color illustrations and accelerated the production process, enabling publishers to satisfy Americans’ steadily increasing demand for books.