CONVERGING MEDIA Case Study: Self-Publishing Redefined

CONVERGINGMEDIACase StudySelf-Publishing Redefined

Media convergence—in the form of e-book readers and e-ink apps for tablets and laptops—is clearly changing the way people read books. But there is another dimension to the e-book revolution that is even more threatening to the traditional print publishing powers: Media convergence is also transforming the way people publish books. Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing has made self-publishing so cheap and easy that, as one Amazon executive put it, “The only really necessary people in the publishing process now are the writer and reader.”1

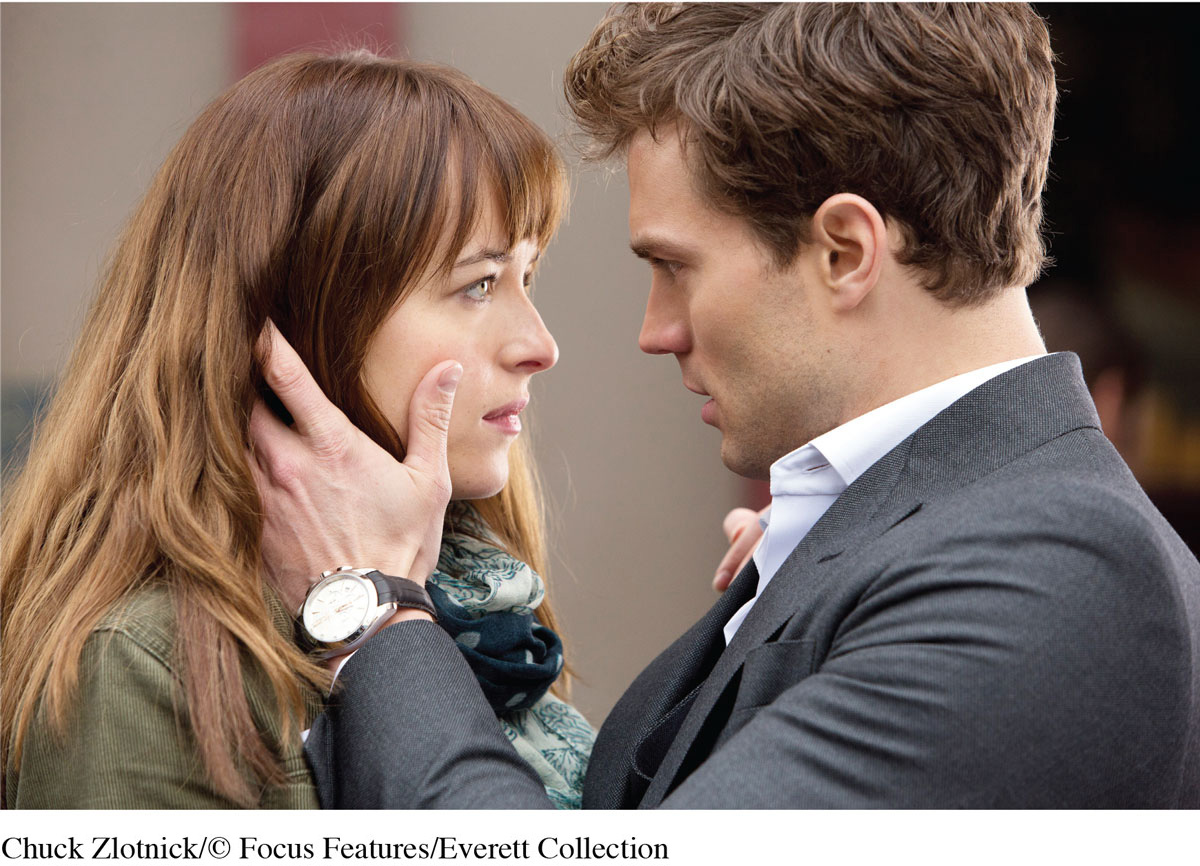

Of course, self-publishing has long been stigmatized as a vain enterprise (hence the term vanity press). Being self-published has been equated with amateurism and work that is not worthy of the considerable expenses and promotional resources associated with one of the big publishing houses. In the new media landscape, however, those notions are becoming increasingly inaccurate. Erika Leonard took the pen name E. L. James and self-published her e-book Fifty Shades of Grey (which she began writing as Twilight fan fiction). When it vaulted to the top of the best-seller list in the e-book format, she signed with publisher Vintage Books, who issued the print version as well as published the following two books in the Fifty Shades trilogy. All three became best-sellers in both formats, and the first book has already been made into a top-grossing movie, with sequels on the way. A self-published expansion of fan fiction became a multimedia empire of sorts. James published an additional spin-off novel in summer 2015, retelling the story from a different point of view.

Visit LaunchPad to watch a clip from the Fifty Shades of Grey trailer. How does the advertising frame the movie?

Visit LaunchPad to watch a clip from the Fifty Shades of Grey trailer. How does the advertising frame the movie?

A number of established authors have also started testing the waters of self-publishing e-books. But the publishing industry response to these flirtations can be harsh. For instance, when Kiana Davenport e-published a compilation of short stories, her publishing house at the time declared that she was “sleeping with the enemy,” canceled the publication of a forthcoming novel, and demanded the return of a $20,000 advance. Davenport then came full circle, signing a new publishing deal with Amazon imprint Thomas & Mercer.2 The established publishers have reason to guard their turf: Self-published authors need not pay 10 percent to a literary agency, and they receive a significantly larger piece of the overall pie. Whereas the authors of paper-based books claim royalties of between 5 and 15 percent, authors with Amazon receive between 35 and 70 percent of the purchase price.3 A 2014 study of author earnings showed self-published books now represent 31 percent of e-book sales on Amazon’s Kindle Store.4

But Amazon’s entry into the publishing world is not limited to simply giving self-published authors a platform. As in the case with Davenport, Amazon is also signing authors to its own publishing arm to produce both print and electronic versions of books.5 Publishers may soon face the kind of competition that booksellers have seen from Amazon over the past decade—and self-publishing authors may still struggle against authors with greater promotional muscle behind them.