The Early History of American Journalism

Human beings have always valued news—the process by which people gather information and create narrative reports to help one another make sense of events happening around them. The earliest news was passed along orally—from family to family and from tribe to tribe—by community leaders and oral historians. Soon after moving from oral to written form, the news shifted from an information source accessible only to elites and local leaders to a mass medium that satisfied a growing audience’s hunger for information. In the earliest days of American newspapers (the late 1600s through the 1800s), written news took on a number of formats—political analyses printed on expensive, handmade paper; cheaper accounts printed on machine-made paper; and sensationalist and investigative reports. Each of these formats fulfilled Americans’ “need to know”—whether they wanted coverage of the political scene, exposés of corruption in business, or even humorous or entertaining perspectives on current events.

Colonial Newspapers and the Partisan Press

Inspired by the introduction of the printing press in Europe, American colonists began producing their first newspapers in the late seventeenth century. Two main types of early papers developed: the partisan press and commercial shipping news. The partisan press got its name because unlike the business models we are familiar with today, these papers were increasingly being sponsored by political parties, politicians, and other partisan groups. They served a vital function before, during, and after the Revolutionary period, critiquing government and disseminating the views of political parties. Other papers were more focused on markets and news about ships that were coming in and out of colonial ports, or they reprinted news (several weeks or months old) from European magazines and newspapers brought on board those ships. In the partisan press, one can see a forerunner to today’s editorial pages as well as partisan cable news channels and Web sites. In the commercial papers, one can see the ancestor of today’s business sections, as well as numerous papers, cable news programs, and Web sites focused on business news.

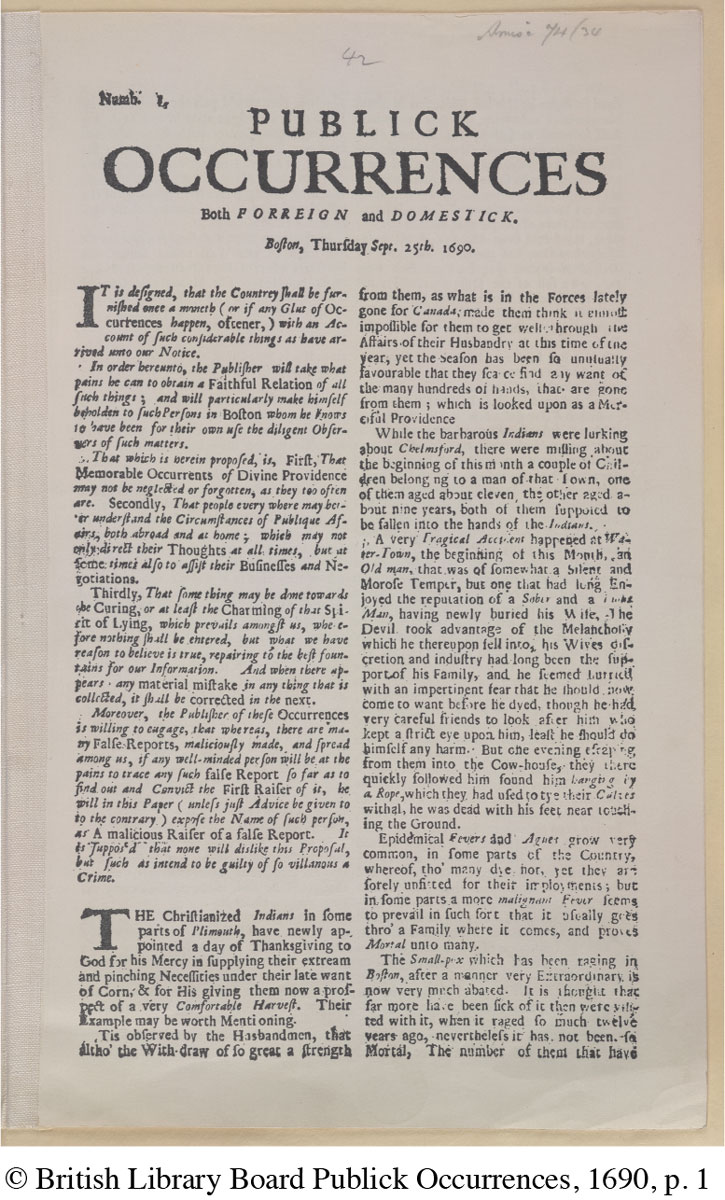

The first newspaper, Publick Occurrences, Both Forreign and Domestick, was published on September 25, 1690, by Boston printer Benjamin Harris, but it was banned after just one issue for its negative view of British rule. In the early 1700s, other papers cropped up, including Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette—which many historians regard as the best of the colonial papers. The Gazette was also one of the first papers to make money by printing advertisements alongside news.

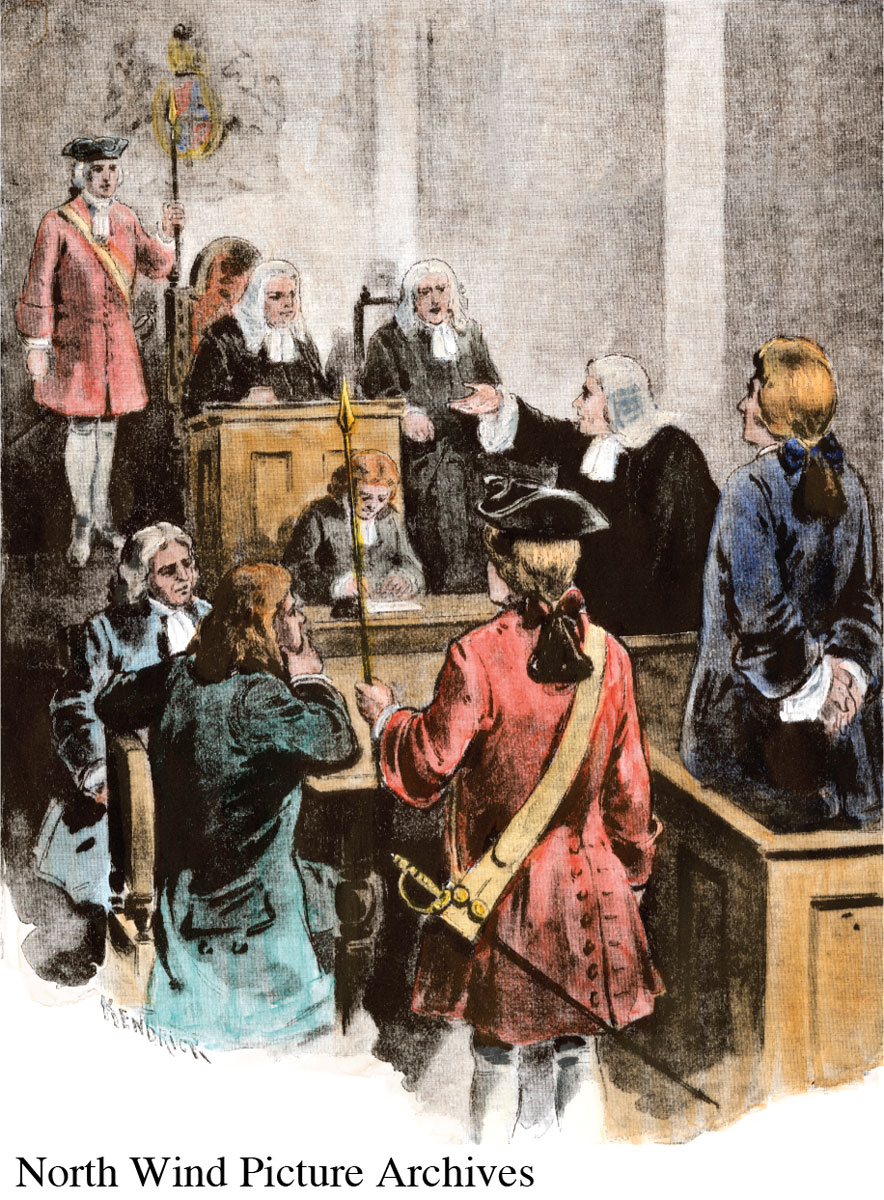

One significant colonial paper, the New-York Weekly Journal, was founded in 1733 by the Popular Party, a political group that opposed British rule. Journal articles included attacks on the royal governor of New York. The party had installed John Peter Zenger as printer of the paper, and in 1734 he was arrested for seditious libel when one of his writers defamed a public official’s character in print. Championed by famed Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton, Zenger won his case the following year. The Zenger decision helped lay a foundation—the right of a democratic press to criticize public officials—for the First Amendment to the Constitution, adopted as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791.

CHAPTER 3 // TIMELINE

1690 First Colonial Newspaper

Boston printer Benjamin Harris publishes Publick Occurrences, Both Forreign and Domestick.

1734 Press Freedom

John Peter Zenger is arrested for seditious libel; jury rules in his favor in 1735, establishing freedom of the press and newspapers’ right to criticize the government.

1827 First African American Newspaper

Freedom’s Journal is founded.

1828 First Native American Newspaper

The Cherokee Phoenix is founded.

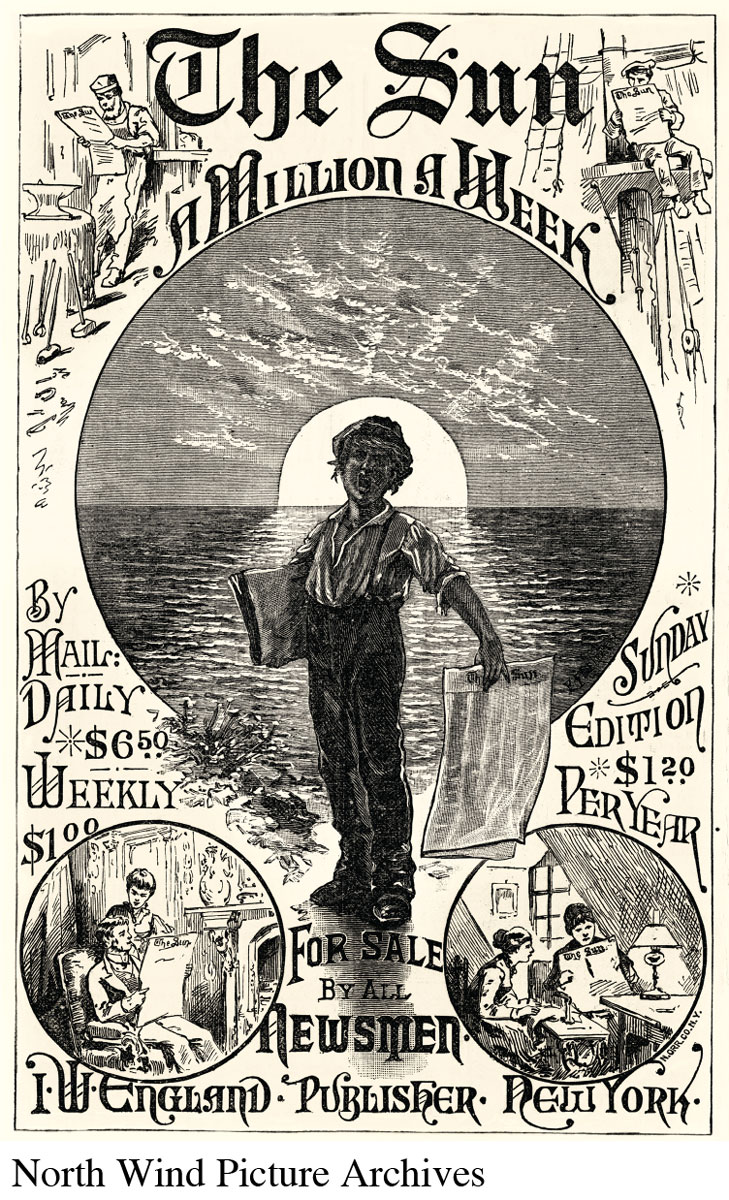

1833 Penny Press

Printer Benjamin Day founds the New York Sun and helps usher in the penny press era.

1848 Associated Press

Six New York newspapers form the Associated Press (AP), relaying news stories around the country via telegraph.

1883 Yellow Journalism

Pulitzer buys the New York World; the battle with Hearst’s New York Journal heats up in 1895 during the heyday of yellow journalism.

1887 Nellie Bly

Nellie Bly’s first article on the conditions in women’s insane asylums is printed in the New York World, an early effort in investigative journalism.

1896 Modern Journalism

Adolph Ochs buys the New York Times, jump-starting modern objective journalism.

1920 First Radio Newscast

The Detroit News, a Scripps-owned newspaper, airs the first radio newscast on August 31 on what would later become WWJ 950 AM.

1948 First Regular Anchored Television Newscasts

CBS Television News starts a regular fifteen-minute nightly newscast with a news anchor (earlier televised news was simulcast from CBS Radio). Newscasts would be extended to a half hour in 1963.

1951 First Television-Newsmagazine-Style Program

Veteran reporter Edward R. Murrow and producer Fred W. Friendly bring their radio-magazine-style show Hear It Now to television, giving it the new name See It Now.

1980 First 24-Hour Cable News

The Cable News Network (CNN) becomes the first television station to provide 24-hour news and information programming.

1980 First Online Paper

Ohio’s Columbus Dispatch becomes the first newspaper to go online.

1982 Postmodern News

Gannett chain launches USA Today, ushering in the postmodern era, in which news is modeled after television.

2009 Some Major Dailies Go Online Only

In the wake of the 2008 recession, some newspapers fail and others, like the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, stop printing paper copies and become online only.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

By 1765, the American colonies boasted about thirty newspapers, all of them published weekly or monthly. In 1784, the first daily paper began operations. But even the largest of these papers rarely reached a circulation of fifteen hundred. Readership was largely confined to educated or wealthy men who controlled local politics and commerce (and who could afford newspaper subscriptions).

The Penny Press: Becoming a Mass Medium

During the 1830s, a number of forces transformed newspapers into an information source available to, valued by, and affordable for all—a true mass medium. For example, thanks to the Industrial Revolution, factories could make cheap, machine-made paper to replace the expensive handmade kind previously in use. At the same time, the rise of the middle class, enabled by the growth of literacy, set the stage for a more popular and inclusive press. And with steam-powered presses replacing mechanical presses, publishers could crank out as many as four thousand copies of their newspapers every hour, which dramatically lowered their cost. Popular penny papers soon began outselling the six-cent elite publications previously available. The success of penny papers would change not only who was reading newspapers but also how those papers were written.

The First Penny Papers

In 1833, printer Benjamin Day founded the New York Sun, lowered the price of his newspaper to one penny, and eliminated subscriptions. The Sun (whose slogan was “It shines for all”) highlighted local events, scandals, and police reports. It also ran fabricated and serialized stories, making legends of frontiersmen Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone and blazing the trail for Americans’ enthusiasm for celebrity news. Within six months, the Sun had a circulation of eight thousand—twice that of its nearest competitor. The Sun’s success unleashed a barrage of penny papers that favored human-interest stories: news accounts that focused on the daily trials and triumphs of the human condition, often featuring ordinary individuals who had faced down extraordinary challenges.

In 1835, James Gordon Bennett founded another daily penny paper, the New York Morning Herald. Considered the first U.S. press baron, Bennett—not any one political party—completely controlled his paper’s content. He established an independent publication that served middle- and working-class readers. The Herald carried political essays and reports of scandals, business stories, a letters section, fashion notes, moral reflections, religious news, society gossip, colloquial tales and jokes, sports stories, and, later, reports from the Civil War fronts. By 1860, the Herald had nearly eighty thousand readers, making it the world’s largest daily paper.

Changing Business Models, Changing Journalism

As ad revenues and circulation skyrocketed, the newspaper industry expanded overall. In 1830, about 650 weekly and 65 daily papers operated in the United States, reaching a circulation of 80,000. Just ten years later, the nation had a total of 1,140 weeklies and 140 dailies, attracting more than 300,000 readers.

As they proliferated and gained new readers, penny papers shifted not just their business models but also the way the news was presented and, as a result, the practice of journalism. Papers had previously been funded primarily by the political parties that sponsored them, and their content emphasized overt political views. But as they expanded, they realized they could derive even more revenues from the market—by selling space for advertisements and by hawking newspapers on the streets and through newsstands. Editors began putting their daily reporting on the front page, moving overt political viewpoints to the editorial page. In other words, as the business model relied more on selling to a mass audience, there was a financial incentive to appeal to customers with a wider range of political beliefs. This trend toward an “objective” style as a result of commercial pressures would also be supported by services that provided content for several different newspapers.

The First News Wire Service

In 1848, the enormous expansion of the newspaper industry led six New York newspapers to form a cooperative arrangement and found the Associated Press (AP), the first major news wire service. Wire services began as commercial and cooperative organizations that relayed news stories and information around the country and the world using telegraph lines (and, later, radio waves and digital transmissions). In the case of the AP, which functioned as a kind of news co-op, the founding New York papers provided access to their own stories and those from other newspapers.

Such companies enabled news to travel rapidly from coast to coast, setting the stage for modern journalism in the United States. And because the papers still cost only a penny, more people than ever now had access to a widening array of news. Clearly, newspapers had moved from the entrepreneurial stage to the status of mass media.

As individual newspapers, which certainly still retained elements of political ideology, became aware of the financial rewards of not alienating those with differing political viewpoints, wire services also saw the need to offer material that as many newspapers as possible would buy. Based on both this economic need and the chance that unreliable telegraph lines might cut off the last part of a report, a journalistic style of writing called the inverted pyramid was developed.

Developed by Civil War correspondents working for individual papers or wire services,2 inverted-pyramid reports were often stripped of adverbs and adjectives, and began—as they do today—with the most dramatic or newsworthy information. They answered the questions who, what, where, when—and, less frequently, why and how—at the top of the story and then narrowed the account down to its less significant details. This approach offered an important advantage: If wars or natural disasters disrupted the telegraph transmissions of these dispatches, at least readers would get the crucial information. Still a staple of introductory news writing courses, this form tends to emphasize immediate events and facts over deeper discussions of context or partisan debate.

But a move away from overt political partisanship on the front page wasn’t the only way the economic desire for larger and larger audiences changed the way journalism was practiced.

Yellow Journalism

Following the tradition established by the New York Sun and the New York Morning Herald, a new brand of papers arose in the late 1800s. These publications ushered in the era of yellow journalism, which emphasized exciting human-interest stories, crime news, large headlines, and easy-to-digest copy. Generally regarded as the direct forerunner of today’s tabloid papers, reality TV, and celebrity-obsessed Web sites like TMZ, yellow journalism featured two major characteristics:

Overly dramatic—or sensational—stories about crime, celebrities, disasters, scandals, and intrigue

News reports exposing corruption, particularly in business and government—the foundation for investigative journalism

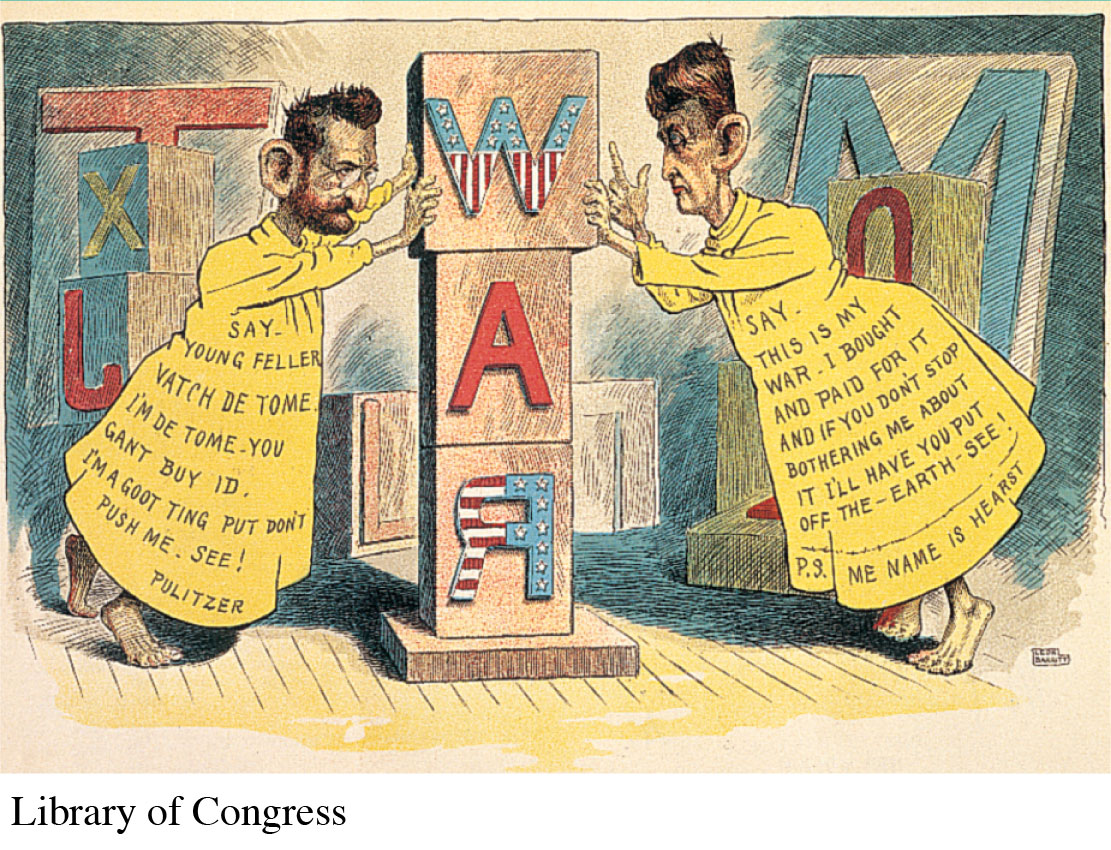

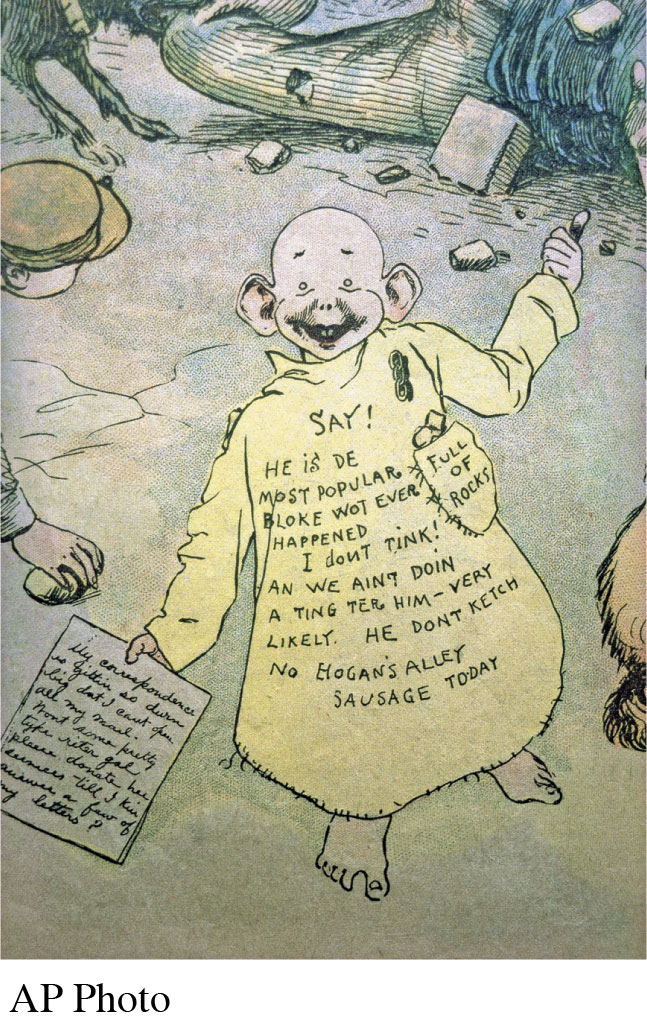

The term yellow journalism has its roots in the press war that pitted Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World against William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. During their furious fight to win readers, the two papers ultimately took turns hosting the first popular cartoon strip, The Yellow Kid, created in 1895 by artist R. F. Outcault. Pulitzer, a Jewish-Hungarian immigrant, had bought the New York World in 1883 for $346,000. Aimed at immigrant and working-class readers, the World crusaded for improved urban housing, better treatment of women, and equitable labor laws, while railing against big business. It also manufactured news events and printed sensationalized stories on crime and sex. By 1887, its Sunday circulation had soared to more than 250,000—the largest anywhere.

The World faced its fiercest competition when William Randolph Hearst in 1895 bought the New York Journal (a penny paper founded by Pulitzer’s brother Albert) and then raided Joseph Pulitzer’s paper for editors, writers, and cartoonists. Hearst focused on lurid, sensational stories and appealed to immigrant readers by using large headlines and bold layout designs. To boost circulation, the Journal invented interviews, faked pictures, and provoked conflicts that might result in eye-catching stories. In 1896, its daily circulation reached 450,000. A year later, the circulation of the paper’s Sunday edition rivaled the World’s 600,000.

Yellow journalism has been vilified for its sensationalism and aggressive tactics to snatch readers from competitors by appealing to their low-brow interests, but this unique era gave birth to several newspaper elements still valued by many readers today, including advice columns and feature stories. It even laid the foundation for the prestigious Pulitzer Prizes, which today recognize quality writing, reporting, and research in such categories as poetry, history, international reporting, editorial cartooning, public service, and explanatory reporting.