Journalism Evolves across Media

The rise of radio and the coming of television would give way to new forms of journalism. Nearly every new mass medium has eventually found a home for journalism of some kind, from radio and television in the first half of the twentieth century, to the addition of cable television in the 1980s, to the emergence and convergence of the Internet in the 1990s through the present day. Many mass media have coexisted with traditional print journalism, but the converged media offered by the Internet has been the catalyst for some of the biggest changes in the journalism world since its early days.

81

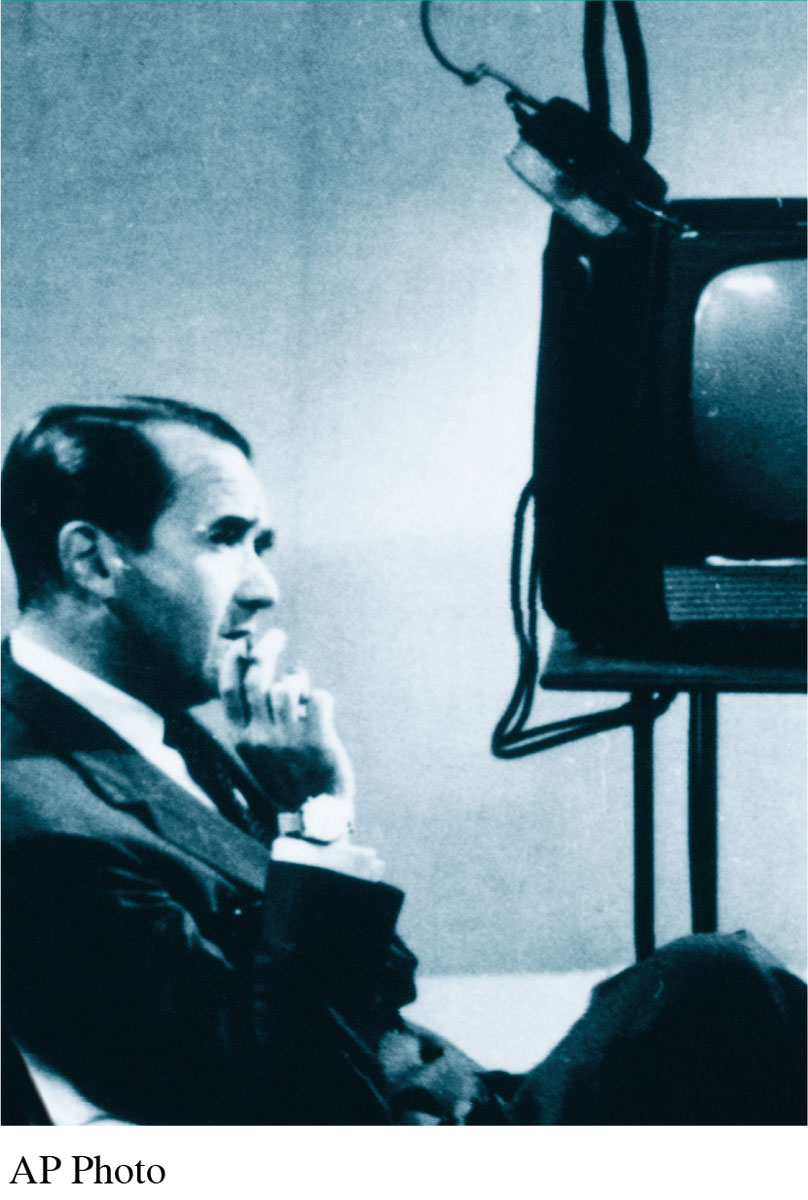

Journalism on the Airwaves

By the time America plunged into the Great Depression, the unique abilities of broadcasting were becoming apparent. For example, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt tapped this potential during his now-famous “fireside chats.” Later, news icon Edward R. Murrow made a name for himself and CBS News during World War II with his broadcasts from rooftops during the bombing of London and his taking a recorder with him as he flew on B-17 bombing missions over Germany, taping commentary for later broadcast. By the 1950s, the rules and rituals surrounding journalism would shift with the popularity of the newest medium, television, to which many radio news icons, such as Murrow, would switch. In 1951, his radio program Hear It Now was retitled See It Now, and it went on to challenge Senator Joseph McCarthy (for his reckless abuse of power and disregard for evidence in the name of labeling others as communists in the United States) and was among the first to warn of the dangers of smoking tobacco. However, as much as Murrow and his work on radio and television are lauded and held in high esteem to this day by broadcast journalists (one of the industry’s highest awards is named after him), it’s worth noting that his coverage of controversial subjects and the accompanying offense taken by advertisers often brought Murrow into conflict with CBS owner William S. Paley and ultimately doomed the program.

The Power of Visual Language

The shift from a print-dominated culture to an electronic-digital culture brings up the question of how the power of visual imagery compares with the power of the printed word. For the second half of the twentieth century, TV news dramatized America’s key events visually. Civil Rights activists, for instance, acknowledge that the movement benefited enormously from televised news that documented the plight of southern blacks in the 1960s in evocative moving images. Many people find visual images far more compelling and memorable than written descriptions of events or individuals. If listening to President Roosevelt on the radio was part of creating a national shared experience, the effect was amplified as a nation watched and celebrated together shared milestones, from the first man to walk on the moon to the inauguration of the first African American U.S. president.

82

84

But just as sound and moving pictures provide powerful communication tools, the technical requirements and styles that have developed also bring along some shortcomings. As previously discussed, TV news reporters share many values and conventions with their print counterparts, yet they also differ from them in significant ways. First, whereas print editors fit stories around ads on the printed page, TV news directors have to time stories to fit between commercials, which can make the ads seem more intrusive to viewers. Second, newspapers can increase or decrease the number of pages, but time is a finite commodity. This has led commercial news operations to often place strict limits on the length of individual news stories (from twenty to ninety seconds in many cases) in the twenty or so minutes of time left in a half-hour newscast after time is taken for commercials. Of that remaining twenty minutes, around half is typically used for local weather and sports. Third, whereas modern print journalists derive their credibility from their apparent neutrality, TV news reporters gain credibility from providing live, on-the-spot reporting; believable imagery; and an earnest, personable demeanor that makes them seem more approachable, even more trustworthy, than the detached, faceless print reporters. As TV news reporting evolved, it developed a style of its own—one defined by attractive, congenial newscasters skilled at perky banter (sometimes called “happy talk”), and short, seven- to eight-second quotes (or “sound bites”) from interview subjects. Print and TV reporters must also compete with Internet-only outlets, which combine elements of both television and print journalism.

Cable News Enters the Field

The transformation of TV news by cable—with the arrival of CNN in 1980—led to dramatic changes in TV news delivery at the national level. Prior to cable news (and the Internet), most people tuned to their local and national news late in the afternoon or evening on a typical weekday, with each program lasting just thirty minutes. But today, the 24/7 news cycle means that we can get TV news anytime, day or night, and the constant need for new content (sometimes called “feeding the beast” by insiders) has led to major changes in what is considered news. Because it is expensive to dispatch reporters to document stories or to maintain foreign news bureaus to cover international issues, the much less expensive “talking head” pundit has become a standard for cable news channels. Such a programming strategy requires few resources beyond the studio and a few guests.

85

Today’s main cable channels have built their evening programs along partisan lines and follow the model of journalism as opinion and assertion: Fox News goes right with pundit stars like Bill O’Reilly (the ratings king of cable news) and Sean Hannity; MSNBC leans left with Rachel Maddow and Lawrence O’Donnell; and CNN stakes out the middle with hosts who try to strike a more neutral pose, like Anderson Cooper. CNN, the originator of cable news, does much more original reporting than Fox News and MSNBC and does better in nonpresidential election years, as well as during natural disasters and crime tragedies.

Broadcast and cable news organizations play an important role in society with their (somewhat) traditional approach to television programming. But it’s nearly impossible to define or describe the current state of journalism, from whatever source, without discussing its convergence with the Internet.

Internet Convergence Accelerates Changes to Journalism

For mainstream print and TV reporters and editors, online news has added new dimensions to journalism. Both print and TV news can continually update breaking stories online, and many reporters now post their online stories first and then work on traditional versions. This means that readers and viewers no longer have to wait until the next day for the morning paper or for the local evening newscast for important stories. To enhance the online reports, which do not have the time or space constraints of television or print, newspaper reporters are increasingly required to provide video or audio for their stories. This allows readers and viewers to see full interviews rather than just selected print quotes in the paper or short sound bites on the TV report. Journalists might augment stories with interactive tools (like maps plotting reports of crimes in a city over time) or a song recording added to the end of an interview with a musician.

However, online news comes with a special set of problems. Print reporters, for example, can do e-mail interviews rather than leave the office to question a subject in person. Many editors discourage this practice because they think relying on e-mail gives interviewees too much control over shaping their answers. Although some might argue that this provides more thoughtful answers, journalists say it takes the elements of surprise and spontaneity out of the traditional news interview, during which a subject might accidentally reveal important information—something less likely to occur in an online setting.

86

Another problem for journalists is, ironically, the wide-ranging resources of the Internet, including access to versions of stories from other papers and broadcast stations. The mountain of information available on the Internet has made it all too easy for journalists to—unwittingly or intentionally—copy other journalists’ work. In addition, access to databases and other informational sites can keep reporters at their computers rather than out tracking down new kinds of information, cultivating sources, and staying in touch with their communities.

Most notable, however, for journalists in the digital age are the demands that convergence has made on their reporting and writing. Print journalists at newspapers (and magazines) are expected to carry digital cameras so that they can post video along with the print versions of their stories. TV reporters are expected to write print-style news reports for their station’s Web site to supplement the streaming video of their original TV stories. And both print and TV reporters are often expected to post the Internet versions of their stories first, before the versions they do for the morning paper or the six o’clock news. In addition, journalists today are increasingly expected to tweet and blog.