The Evolution of Modern American Magazines

As the sun set on the nineteenth century, decreases in postage costs made it cheaper for publishers to distribute magazines, and improvements in production technologies lowered the costs of printing them. Now accessible and affordable to ever-larger audiences, magazines became a true mass medium. They also began reflecting the social, demographic, and technological changes unfolding within the nation as the twentieth century progressed. For example, a new interest in social reform sparked the rise of muckraking, or investigative journalism designed to expose wrongdoing. The growth of the middle class initially heightened receptivity to general-interest magazines aimed at broad audiences, but then television’s rising popularity put many general-interest magazines out of business. Some magazines struck back by focusing their content on topics not covered by TV programmers and by featuring short articles heavily illustrated with photos.

Distribution and Production Costs Plummet

In 1870, about twelve hundred magazines were being produced in the United States; by 1890, that number had reached forty-five hundred. By 1905, the nation boasted more than six thousand magazines. Part of this surge in titles and readership was facilitated by the Postal Act of 1879, which assigned magazines lower postage rates—putting them on an equal footing with newspapers delivered by mail. This vastly reduced distribution costs. Meanwhile, advances in mass-production printing, conveyor systems, assembly lines, and printing press speeds lowered production costs and made large-circulation national magazines possible.

120

This combination of reduced distribution and production costs enabled publishers to slash magazine prices. As prices dropped from thirty-five cents to fifteen and then to ten cents, people of modest means began subscribing to national publications. Magazine circulation skyrocketed, attracting new waves of advertising revenues. Even though publishers had dropped the price of an issue below the actual cost to produce a single copy, they recouped the loss through ad revenue—guaranteeing large readerships to advertisers eager to reach more customers. By the turn of the twentieth century, advertisers increasingly used national magazines to capture consumers’ attention and build a national marketplace.

Muckrakers Expose Social Ills

The rise in magazine circulation coincided with major changes in American society in the early 1900s. Americans were moving from the country to the city in search of industrial jobs, and millions were immigrating to the United States hoping for new opportunities. Many newspaper reporters interested in writing about these and other social changes turned to magazines, for which they could write longer, more analytical pieces on such topics as corruption in big business and government, urban problems faced by immigrants, labor conflicts, and race relations. Some of these writers built their careers on crusading for social reform on behalf of the public good—often criticizing long-standing American institutions.

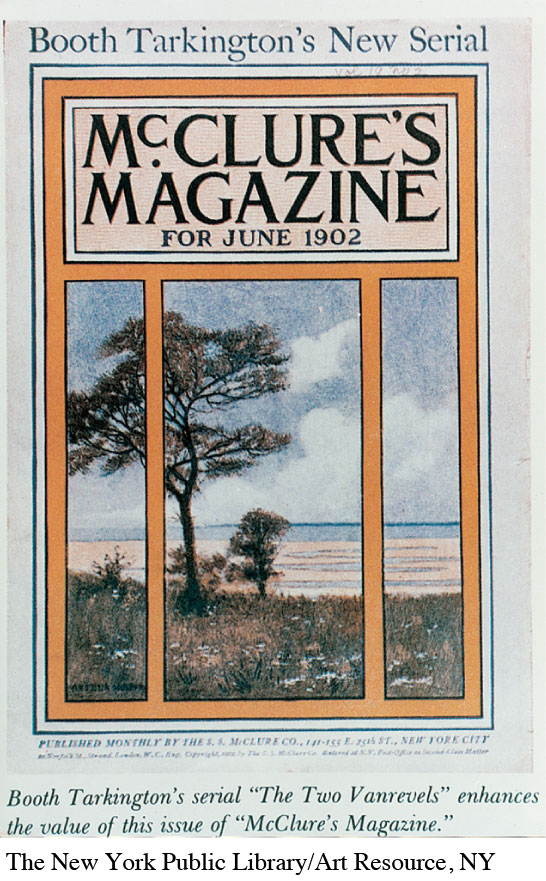

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt dubbed these investigative reporters muckrakers, because they were willing to crawl through society’s muck to uncover a story. Although Roosevelt wasn’t always a fan, muckraking journalism led to some much-needed reforms. For example, influenced in part by exposés at Ladies’ Home Journal and Collier’s magazines, Congress in 1906 passed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act. Reports in Cosmopolitan, McClure’s, and other magazines led to laws calling for increased government oversight of business, a progressive income tax, and the direct election of U.S. senators.

General-Interest Magazines Hit Their Stride

The heyday of the muckraking era lasted into the mid-1910s, when America was drawn into World War I. During the next few decades and even through the 1950s, general-interest magazines gained further prominence. These publications covered a wide variety of topics aimed at a broad national audience—such as recent developments in government, medicine, or society. A key aspect of these magazines was photojournalism—the use of photographs to augment editorial content (see “Media Literacy Case Study: The Evolution of Photojournalism”). High-quality photos gave general-interest magazines a visual advantage over radio, which was the most popular medium of the day. In 1920, about fifty-five magazines fit the general-interest category; by 1946, more than a hundred such magazines competed with radio networks for the national audience. Four giants dominated this magazine genre: the Saturday Evening Post, Reader’s Digest, Time, and Life.

121

Saturday Evening Post

Although the Post had been around since 1821, it didn’t become the first widely popular general-interest magazine until 1897. The Post printed popular fiction and romanticized American virtues through words and pictures. During the 1920s, it also featured articles celebrating the business boom of the decade. This reversed the journalistic direction of the muckraking era, in which magazines focused on exposing corruption in business. By the 1920s, the Post had reached two million in circulation, the first magazine to hit that mark.

Reader’s Digest

Reader’s Digest championed one of the earliest functions of magazines: printing condensed versions of selected articles from other magazines. With its inexpensive production costs, low price, and popular pocket-size format, the magazine saw its circulation climb to more than one million even during the depths of the Great Depression. By 1946, it was the nation’s most popular magazine. By the mid-1980s, it was the most popular magazine in the world.

Time

During the general-interest era, national newsmagazines such as Time also scored major commercial successes. Begun in 1923, Time developed a magazine brand of interpretive journalism, assigning reporter-researcher teams to cover newsworthy events, after which a rewrite editor would shape the teams’ findings into articles presenting a point of view on the events covered. Newsmagazines took over photojournalism’s role in news reporting, visually documenting both national and international events. Today, Time’s circulation stands at about 2.6 million.

Life

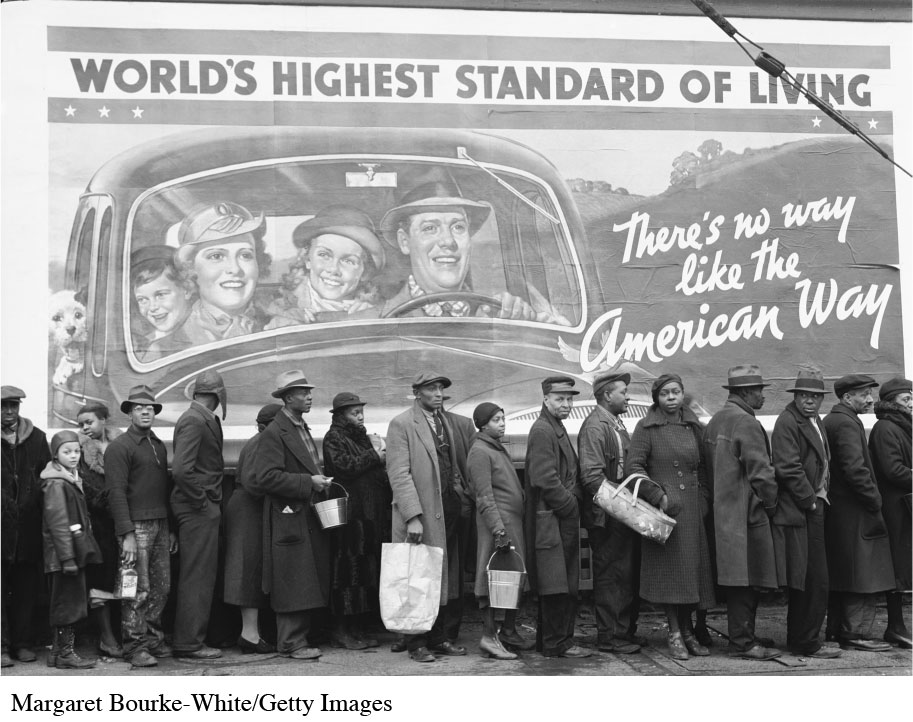

More than any other magazine of its day, Life, an oversized pictorial weekly, struck back at radio’s popularity by advancing photojournalism. Launched in 1936, Life satisfied the public’s fascination with images (invigorated by the movie industry) by featuring extensive photo spreads with its researched articles, lavish advertisements, and even fashion photography. By the end of the 1930s, Life had a pass-along readership—the total number of people who come into contact with a single copy of a magazine—of more than seventeen million. This rivaled the ratings of even the most popular national radio programs.

122

General-Interest Magazines Decline

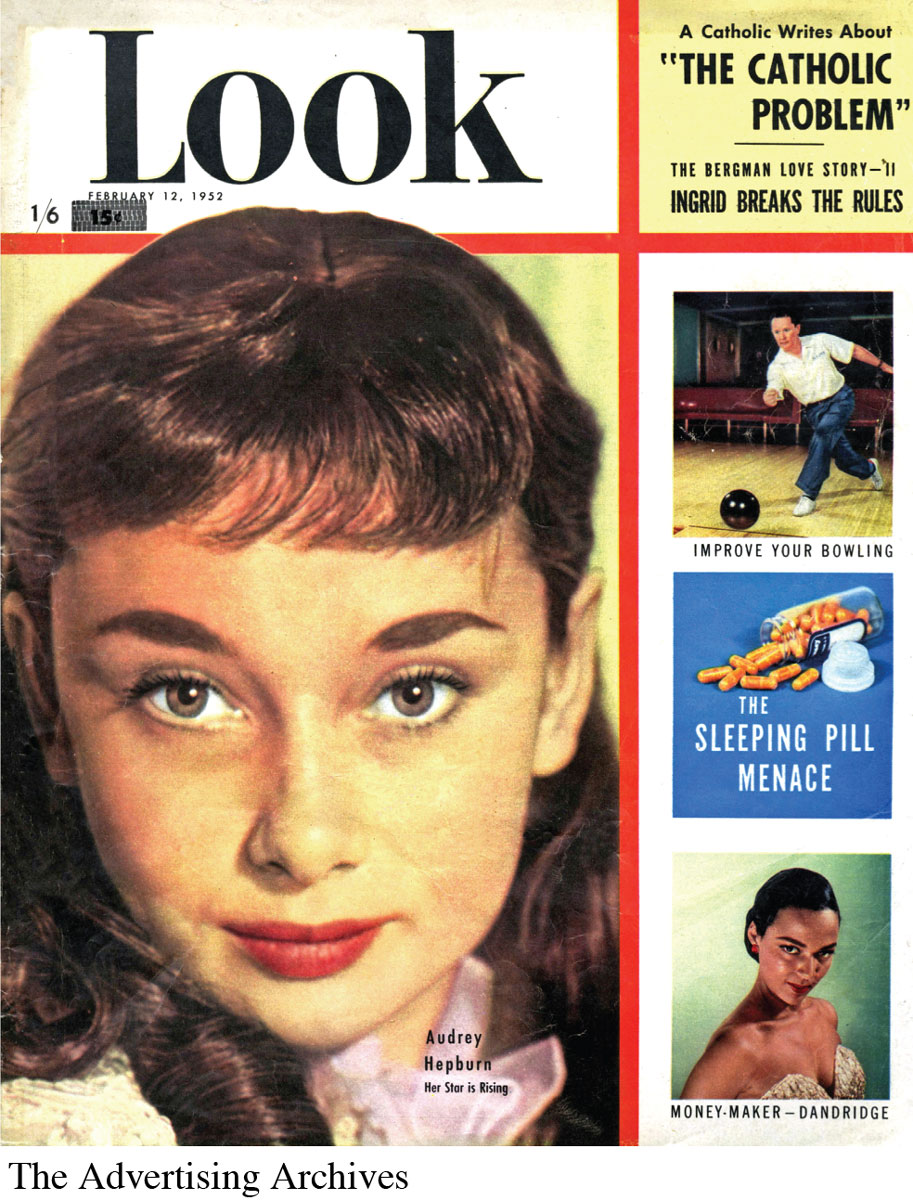

In the 1950s, weekly general-interest magazines began to lose circulation after dominating the industry for thirty years. Following years of struggle, the Saturday Evening Post finally folded in 1969; Look (another oversized pictorial weekly), in 1971; and Life, in 1972. Oddly, all three at the time were in the Top 10 in paid circulation. Although some critics attributed the problem to poor management, general-interest magazines were victims of several forces: high production costs, increased postal rates, and—in particular—television. As families began spending more time gathered around their TVs instead of reading magazines, advertisers began spending more money on TV spots, which were less expensive than magazine ads and reached a larger audience.

TV Guide

Launched in 1953 to exploit the nation’s growing fascination with television, TV Guide, which published TV program listings, took its cue from the pocket-size format of Reader’s Digest and the supermarket sales strategy used by women’s magazines. By filling a need (many newspapers were not yet listing TV programs), the magazine by 1962 had become the first weekly to reach a circulation of eight million. At that time, it had seventy regional editions. (See Table 4.1 for the circulation figures of the Top 10 U.S. magazines.)

When local newspapers began listing TV program schedules, they undermined TV Guide’s regional editions, and the magazine saw its circulation decline. In response, the magazine transformed itself to survive. Today, TV Guide is a full-size, single-edition, national magazine, having dropped its smaller digest format and its 140 regional editions in 2005. It now focuses on entertainment and lifestyle news and carries only limited listings of cable and network TV schedules. The brand name also lives on in the TV Guide Network—an on-screen cable and satellite TV program guide—and TVGuide.com.

People

People (launched by Time Inc. in March 1974) capitalized on the celebrity-crazed culture that accompanied the rise of television. And, like TV Guide, it crafted a distribution strategy emphasizing supermarket sales. These moves helped it become the first successful mass market magazine to be introduced in decades. With an abundance of celebrity profiles and human-interest stories, People showed a profit in just two years and reached a circulation of more than two million within five years. Instead of using a bulky oversized format and relying on subscriptions, People downsized and generated most of its circulation revenue from newsstand and supermarket sales. To this day, it uses plenty of photos, and its articles are about one-third the length of those in a typical newsmagazine. People’s success has inspired the launching of similar magazines specializing in celebrities, human-interest stories, and fashion, such as InStyle and Hello, and has influenced competing Webzines like TMZ and Wonderwall.

| 1972 | 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank/Publication | Circulation | Rank/Publication | Circulation |

| 1 Reader’s Digest | 17,825,661 | 1 AARP The Magazine | 22,274,096 |

| 2 TV Guide | 16,410,858 | 2 AARP Bulletin | 22,244,820 |

| 3 Woman’s Day | 8,191,731 | 3 Game Informer | 7,629,995 |

| 4 Better Homes and Gardens | 7,996,050 | 4 Better Homes and Gardens | 7,615,641 |

| 5 Family Circle | 7,889,587 | 5 Good Housekeeping | 4,348,641 |

| 6 McCall’s | 7,516,960 | 6 Reader’s Digest | 4,288,529 |

| 7 National Geographic | 7,260,179 | 7 Family Circle | 4,092,525 |

| 8 Ladies’ Home Journal | 7,014,251 | 8 National Geographic | 4,029,881 |

| 9 Playboy | 6,400,573 | 9 People | 3,527,541 |

| 10 Good Housekeeping | 5,801,446 | 10 Woman’s Day | 3,311,803 |

124