MEDIA LITERACY Case Study: The Evolution of Photojournalism

MEDIALITERACYCase StudyThe Evolution of Photojournalism

By Christopher R. Harris

What we now recognize as photojournalism started with the assignment of photographer Roger Fenton, of the Sunday Times of London, to document the Crimean War in 1856. Since then—from the earliest woodcut technology to halftone reproduction to the flexible-film camera—photojournalism’s impact has been felt worldwide, capturing many historic moments and playing important political and social roles. For example, Jimmy Hare’s photoreportage on the sinking of the battleship Maine in 1898 near Havana, Cuba, fed into growing popular support for Cuban independence from Spain and eventual U.S. involvement in the Spanish-American War; and the documentary photography of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine at the turn of the twentieth century captured the harsh working and living conditions of the nation’s many child laborers. Reaction to these shockingly honest photographs resulted in public outcry and new laws against the exploitation of children. In addition, Time magazine’s coverage of the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression and Life’s images from World War II and the Korean War changed the way people viewed the world.

Visit LaunchPad to watch a clip about the power of photojournalism. How does it relate to the content of this box?

Visit LaunchPad to watch a clip about the power of photojournalism. How does it relate to the content of this box?

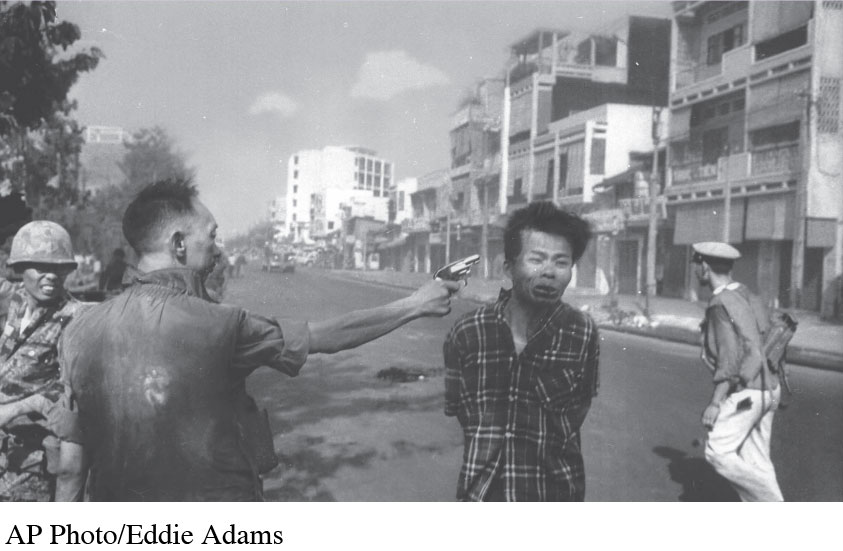

With the advent of television, photojournalism continued to take on a significant role, bringing to the public live coverage of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and its aftermath as well as visual documentation of the turbulent 1960s, including aggressive photographic coverage of the Vietnam War and shocking images of the Civil Rights movement.

Into the 1970s and onward, the emergence of computer technologies has raised new ethical concerns about photojournalism. These new concerns deal primarily with the ability of photographers and photo editors to change or digitally alter the documentary aspects of a news photograph. By the late 1980s, computers could transform images into digital form, easily manipulated by sophisticated software programs. In addition, any photographer can now send images around the world almost instantaneously through digital transmission, and the Internet allows publication of virtually any image without censorship. Because of the absence of physical film, there is a resulting loss of proof, or veracity, of the authenticity of images. Digital images can be easily altered, but such alteration can be very difficult to detect.

A recent example of tampering with a famous image involved an Orthodox Jewish newspaper in Brooklyn that deleted then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and counterterrorism director Audrey Tomason from a photograph of President Barack Obama and other White House staff monitoring the Navy Seals raid that killed Osama bin Laden. The paper does not publish images of women in accordance with Orthodox Jewish rules about modesty and ignored White House conditions that the supplied photo not be altered. They issued an apology shortly thereafter.

Have photo editors gone too far? Photojournalists and news sources are now confronted with unprecedented concerns over truth-telling. In the past, trust in documentary photojournalism rested solely on the verifiability of images as they were used in the media. Now, news sources have a variety of guidelines in place regarding image manipulations, ranging from vague requirements that the image not be changed in a misleading way to specific lists of acceptable Photoshop tools. Just as we must evaluate the words we read, at the start of a new century we must also view with a more critical eye these images that mean so much to so many.

APPLYING THE CRITICAL PROCESS

DESCRIPTION Select three types of magazines (e.g., national, political, and alternative) that contain photojournalistic images. Look through these magazines, taking note of what you see.

ANALYSIS Document the patterns in each magazine. What kinds of images are included? What kinds of topics are discussed? Do certain stories or articles have more images than others? Are the subjects generally recognizable, or do they introduce readers to new people or places? Do the images accompany an article or are they stand-alone, with or without a caption?

INTERPRETATION What do these patterns mean? Talk about what you think the orientation is of each magazine based on the images. How do the photos work to achieve this view? Do the images help the magazine in terms of verification or truth-telling? Or are the images mainly to attract attention? Can images do both?

EVALUATION Do you find the motives of each magazine to be clear? Can you see any examples in which an image may have been framed or digitally altered to convey a specific point of view? What are the dangers in this? Explain.

ENGAGEMENT If you find evidence that a photo has been altered or has framed the subject in a manner that makes it less accurate, e-mail the magazine’s editor and explain why you think this is a problem.

Christopher R. Harris is a professor in the Department of Electronic Media Communication at Middle Tennessee State University.