Chapter Introduction

5

Sound Recording

and Popular Music

In September 2014, rock band U2 teamed up with Apple to offer what it thought was going to be a successful promotion: giving away its new album, Songs of Innocence, for free to over 500 million iTunes subscribers. Instead, it set off a major backlash. Some users were upset that the album had automatically downloaded and was taking up space on their devices or in their cloud accounts. Some musicians worried that less-wealthy groups would suffer in a marketplace accustomed to free music. Before the controversy died down, Apple had to create an app with easy-to-follow instructions for those wanting to remove the album.

There is a note of irony to this backlash of consumer anger over free digital music, because it was the desire to download free music that kicked off the ongoing transformation of the sound recording industry. Shawn Fanning, John Fanning, and Sean Parker launched music-sharing site Napster in 1999. Although not the first service to let people share music files online, it combined the lure of free music with an easy-to-use interface that rapidly increased its popularity with users—and its unpopularity with music companies and many artists. Ultimately, the courts agreed with the record labels and artists who complained about copyright infringement, and shut down the service in 2001. Other file-sharing services sprang up, but the next big development was the launch of iTunes in 2003, an online music store from which people could buy individual songs instead of entire albums. Downloaded music sales from iTunes and other sources skyrocketed, only beginning to slow down recently due to competition from streaming services like Spotify and Pandora.

So with all of these changes in the business side of the music business, why did U2 decide to give away an album for free? In this case, U2 did get paid, but from Apple rather than from consumers. In addition to an undisclosed payment, Apple agreed to spend $100 million on a marketing campaign for the band, which could be especially lucrative for a big-name band capable of drawing big crowds willing to pay premium ticket prices.

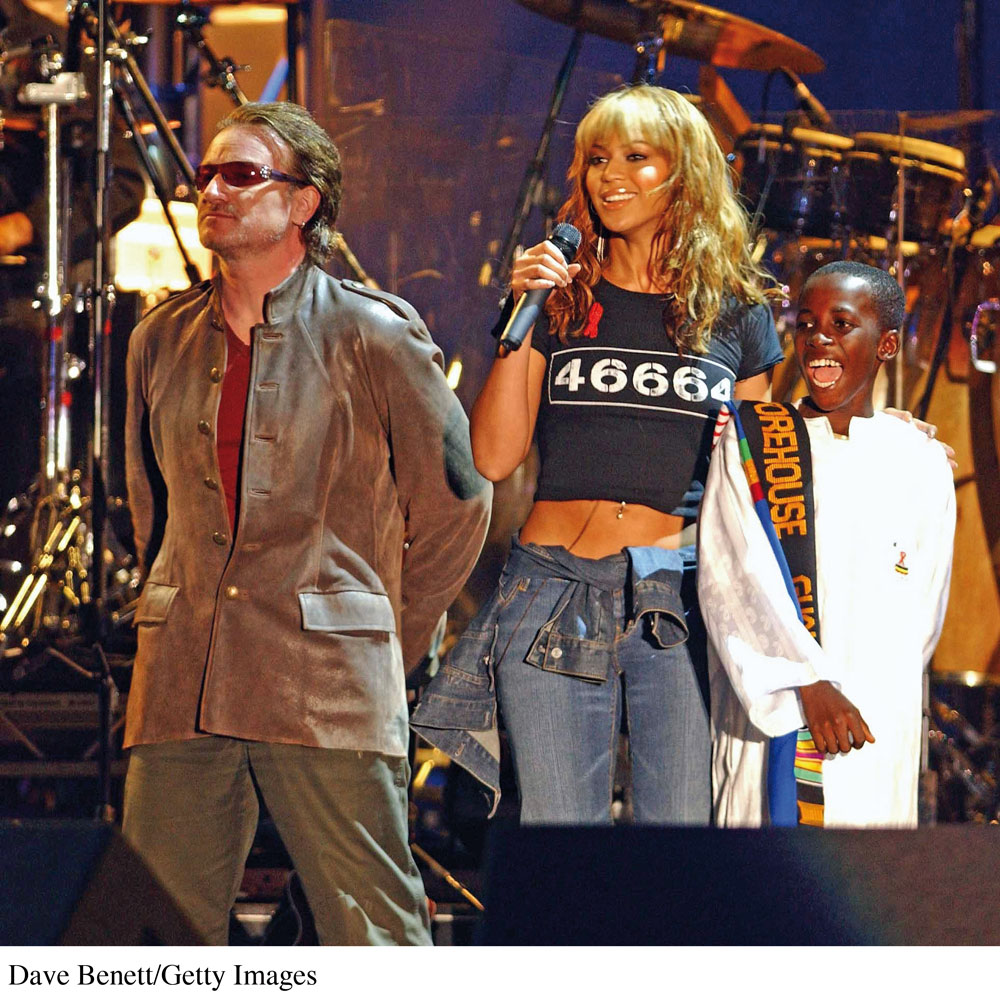

U2’s approach was the latest example of artists looking for ways to take advantage of convergence and the power of social media—that is, to make money in new ways. For example, Beyoncé dropped a surprise album in December 2013, using social media to create buzz, share music videos, and push pre-holiday sales. The band Radiohead took another approach in 2007, making songs from the album In Rainbows available online, asking fans to pay what they thought was fair (actual CDs were available a couple months later). Marketing also converged with the Internet (including YouTube and social media sites) to help launch the careers of less established artists like Justin Bieber and Iggy Azalea, and help independent artists Macklemore & Ryan Lewis top the music charts.1

Although predictions about Napster ending the music industry haven’t come true, the Internet age has seen music industry revenue cut in half (from $14.5 billion in 1998 to about $7 billion in 2013), and the growing popularity of music streaming services could mean that number will continue to fall. One prediction that is likely to come true is that the music industry will continue to search out new strategies. Taylor Swift, one of music’s biggest stars, actually moved away from streaming when her album 1989 was released, going so far as to take all of her previous albums off of Spotify, arguing that artists should be paid more by streaming sites (where typically only the most successful artists, like Swift, can make substantial money). Artists with less leverage than Swift (which is to say, most of them) may soon use songs as loss leaders: products labels know up front will not make money on their own but will act as marketing for more lucrative licensing deals and concert tours (see also “Converging Media Case Study: 360 Degrees of Music,”). However the music industry proceeds, it will continue to look very different from how it looked even just a few years ago.

THE INVENTION OF SOUND RECORDING TECHNOLOGY transformed our relationship with popular music and made sound recording a mass medium. Before recording, people had one way to listen to music: attend a live performance. With the advent of sound recording, people could also buy recordings and listen to their favorite music as often as they wanted in their own homes. As technological advances made it cheaper and easier for everyone to gain access to sound recordings, music began reshaping society and culture. But the recording industry itself has also changed with the times. Consider what happened in the 1950s after TV began capturing a bigger share of Americans’ attention and time: Record labels and radio stations—previously adversaries—joined forces to create Top 40 (or “hit song”) programming to attract more listeners and stimulate music sales. Many years later, the industry was forced to shift again in the face of technology, as the MP3 format made recorded music more accessible (and easier to duplicate) than ever.

In this chapter, we assess the full impact of sound recording and popular music on our lives by:

examining the early history and evolution of sound recording, including the shift from analog to digital technology and the changing relationship between record labels and radio stations

shining a spotlight on the rise of popular music (including jazz, rock, and country) in the United States

tracing the changes in the American popular-music scene, such as rock’s move into the mainstream and the proliferation of rock alternatives (including folk and grunge)

analyzing the economics of the sound recording industry, including how music labels, artists, and other participants make and spend money

considering sound recording’s impact on our democratic society today by exploring such questions as whether the recording industry is broadening participation in democracy or constraining it