The Early History and Evolution of Sound Recording

Early inventors’ work helped make sound recording a mass medium and a product that enterprising businesspeople could sell. The product’s format changed with additional technological advances (e.g., moving from records and tapes to CDs, and then to online downloads and digital music streaming). Technology also enhanced the product’s quality; for example, many people praised the digital clarity of CDs over “scratchy” analog recordings. However, the latest technology—online downloading and streaming of music—has drastically reduced sales of CDs and other physical formats, forcing industry players to look for other ways to survive.

From Cylinders to Disks: Sound Recording Becomes a Mass Medium

In the development stage of sound recording, inventors experimented with sound technology; and in the entrepreneurial stage, people sought to make money from the technology. Sound recording finally reached the mass medium stage when entrepreneurs figured out how to quickly and cheaply produce and distribute multiple copies of recordings.

The Development Stage

In the 1850s, French printer Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville conducted the first experiments with sound recording. Using a hog’s-hair bristle as a needle, he tied one end to a thin membrane stretched over the narrow part of a funnel. When he spoke into the wide part of the funnel, the membrane vibrated, and the bristle’s free end made grooves on a revolving cylinder coated with a thick liquid. Although de Martinville never figured out how to play back the sound, his experiments ushered in the development stage of sound recording.

The Entrepreneurial Stage

In 1877, Thomas Edison helped move sound recording into its entrepreneurial stage by first determining how to play back sound, then marketing the machine that did it. He recorded his own voice by concocting a machine that played foil cylinders, known as the phonograph (derived from the Greek terms for “sound” and “writing”). Edison then patented his phonograph in 1878 as a kind of answering machine. In 1886, Chichester Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter patented an improvement on the phonograph, known as the graphophone, which played more durable wax cylinders.2 Both Edison’s phonograph and Bell and Tainter’s graphophone had only marginal success as a voice-recording office machine. Yet these inventions laid the foundation for others to develop more viable sound recording technologies.

The Mass Medium Stage

Adapting ideas from previous inventors, Emile Berliner, a German engineer who had immigrated to America, made sound recording into a mass medium. Berliner developed a turntable machine that played flat disks, or “records,” made of shellac. He called this device a gramophone and patented it in 1887. He also discovered how to mass-produce his records by making a master recording from which many copies could be easily duplicated. In addition, Berliner’s records could be stamped in the center with labels indicating song title, performer, and songwriter.

By the early 1900s, record-playing phonographs were widely available for home use. Early record players, known as Victrolas, were mechanical and had to be primed with a crank handle. Electric record players, first available in 1925, gradually replaced Victrolas as more homes were wired for electricity.

Recorded music initially had limited appeal, owing to the loud scratches and pops that interrupted the music, and each record contained only three to four minutes of music. However, in the early 1940s, when shellac was needed for World War II munitions, the record industry began manufacturing records made of polyvinyl plastic. These vinyl records (called 78s because they turned at seventy-eight revolutions per minute, or rpms) were less noisy and more durable than shellac records. Enthusiastic about these new advantages, people began buying more records.

In 1948, CBS Records introduced the 33⅓-rpm long-playing record (LP), which contained about twenty minutes of music on each side. This created a market for multisong albums and classical music, which was written primarily for ballet, opera, ensemble, or symphony, and continues to have a significant fan base worldwide. The next year, RCA developed a competing 45-rpm record, featuring a quarter-size hole in the middle that made these records ideal for playing in jukeboxes. The two new recording configurations could not be played on each other’s machines; thus, a marketing battle erupted. In 1953, CBS and RCA compromised. The LP became the standard for long-playing albums, the 45 became the standard for singles, and record players were designed to accommodate both formats (as well as 78s, at least for a while).

From Records to Tapes to CDs: Analog Goes Digital

The advent of magnetic audiotape and tape players in the 1940s paved the way for major innovations, such as cassettes, stereophonic sound, and—most significantly—digital recording. Audiotape’s lightweight magnetized strands made possible sound editing and multiple-track mixing, in which instrumentals or vocals could be recorded at one location and later mixed onto a master recording in a studio. This vastly improved studio recordings’ quality and boosted sales, though recordings continued to be sold primarily in vinyl format until the late 1970s.

By the mid-1960s, engineers had placed miniaturized (reel-to-reel) audiotape inside small plastic cases and developed portable cassette players. Listeners could now bring recorded music anywhere, which created a market for prerecorded cassettes. Audiotape also permitted home dubbing, which began eroding record sales.

Some people thought audiotape’s portability, superior sound, and recording capabilities would mean the demise of records. However, vinyl’s popularity continued, due in part to the improved fidelity that came with stereophonic sound. Invented in 1931 by Alan Blumlein, but not put to commercial use until 1958, stereo permitted the recording of two separate channels, or tracks, of sound. Using audiotape, recording-studio engineers could now record many instrumental or vocal tracks, which they would then “mix down” to two stereo tracks, creating a more natural sound.

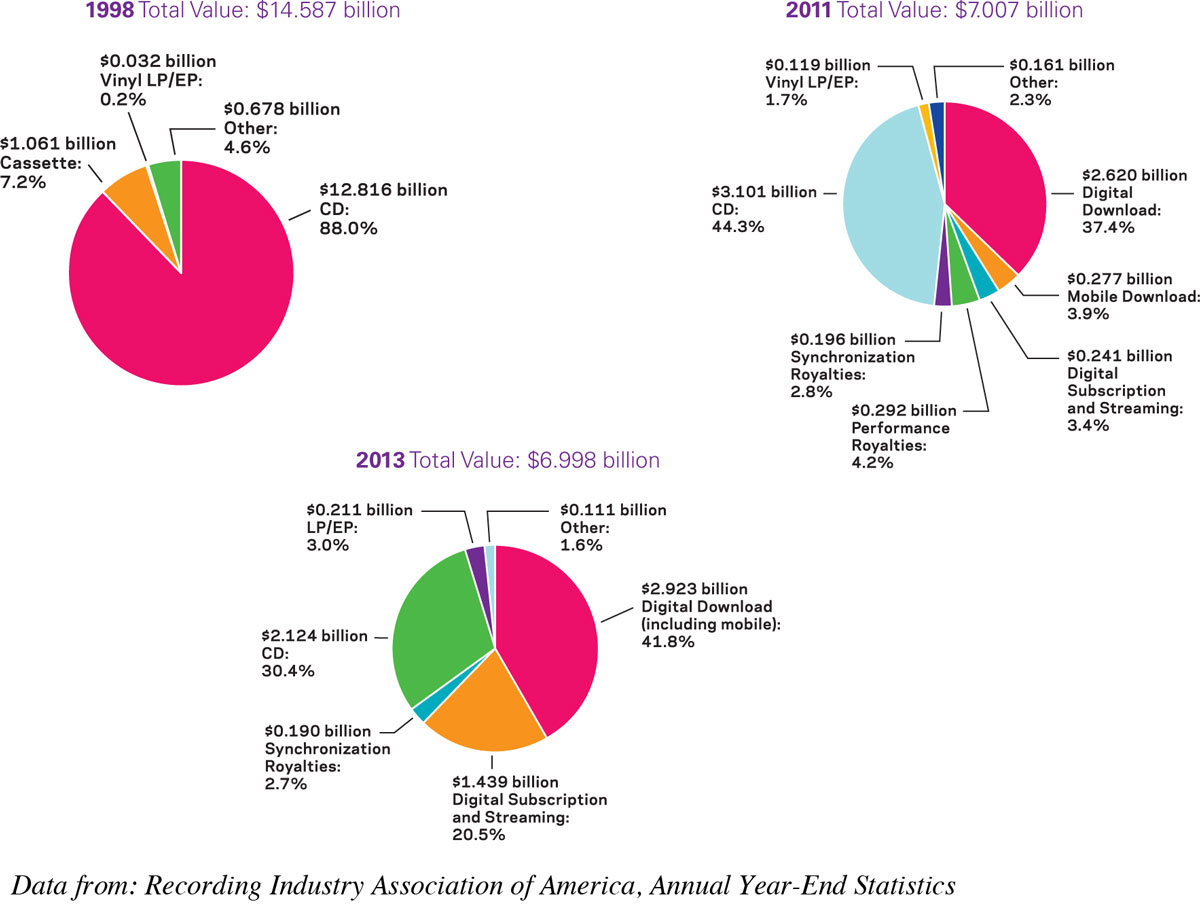

The biggest recording advancement came in the 1970s, when electrical engineer Thomas Stockham made the first digital audio recordings on standard computer equipment. In contrast to analog recording, which captures the fluctuations of sound waves and stores those signals in a record’s grooves or a tape’s continuous stream of magnetized particles, digital recording translates sound waves into binary on-off pulses and stores that information in sequences of ones and zeros as numerical code. Drawing on this technology, in 1983 Sony and Philips began selling digitally recorded compact discs (CDs), which could be produced more cheaply than vinyl records and even audiocassettes. By 2000, CDs had rendered records and audiocassettes nearly obsolete except among deejays, hip-hop artists (who still used vinyl for scratching and sampling), and some audiophile loyalists (see Figure 5.1). In a fairly recent development, however, vinyl albums, once nearly extinct, have been making a comeback. Still a relatively small part of the overall market in music sales, vinyl sales have jumped so much that many new albums are being pressed on vinyl. Some record-pressing plants have even reopened, and others have been built, just to keep up with demand. Whether this will be a lasting or a brief trend among a new wave of collectors (many of whom were born after the introduction of CDs) remains to be seen.

CHAPTER 5 // TIMELINE

1850s de Martinville

The first experiments in sound recording are conducted using a hog’s-hair bristle as a needle; de Martinville can record sound but is unable to play it back.

1877 Phonograph

Edison invents the phonograph as a way to play back sound.

1887 Flat Disk

Berliner invents the flat disk and the gramophone on which to play it. The disks are easily mass-produced, and sound recording becomes a mass medium.

1910 Victrolas

Music players enter living rooms.

1925 Radio Threatens the Sound Recording Industry

Music can be heard over the airwaves, prompting ASCAP to establish fees for radio.

1940s Audiotape

Developed in Germany, audiotape enables multitrack recording.

1950s Music Industry

As television threatens radio, radio turns to the music industry for salvation and becomes a marketing arm for the sound recording industry.

1950s Rock and Roll

This new music form challenges class, gender, race, geographic, and religious norms in the United States.

1953 A Sound Recording Standard

This is established at 33

rpm for long-playing albums (LPs), 45 rpm for two-sided singles.

rpm for long-playing albums (LPs), 45 rpm for two-sided singles.1960s Cassettes

This new format makes music portable.

Late 1970s Hip-Hop

This musical art form emerges.

1983 CDs

The first format to incorporate digital technology hits the market.

2000 Napster

A recently developed format that compresses music into digital files shakes up the industry as millions of Internet users share music files on Napster.

2001 File-Sharing

A host of new peer-to-peer Internet services make music file-sharing more popular than ever.

2008 Online Music Stores

Apple’s iTunes becomes the No. 1 retailer of music in the United States.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

Recording Music Today

Composer Scott Dugdale discusses technological innovations in music recording.

Discussion: What surprised you the most about song production as shown in the video?

From CDs to MP3s: Sound Recording in the Internet Age

In 1992, the MP3 file format was developed as part of a video compression standard. As it turns out, the format also enables sound, including music, to be compressed into small, manageable digital files. Combined with the Internet, the MP3 format revolutionized sound recording. By the mid-1990s, computer users were swapping MP3 music files online. These files could be uploaded and downloaded in a fraction of the time it took to exchange noncompressed music, and they used up less memory.

In 1999, Napster’s now-infamous free file-sharing service brought MP3s to popular attention. By then, music files were widely available on the Internet—some for sale, some available legally for free downloading, and many traded in violation of copyright laws. Losing countless music sales to free downloading, the music industry initiated lawsuits against file-sharing companies and individual downloaders.

In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the music industry and against Napster, declaring free music file-swapping illegal because it violated music copyrights held by recording labels and artists. Yet even today, illegal swapping continues at a high level—in part because of how difficult it is to police the decentralized Internet. Music MP3s (some acquired legally, some not) are now played on computers, home stereo systems, car stereos, portable devices, and cell phones. In fact, MP3 is now the leading music format. (For more on music sales, see “Media Literacy Case Study: The Rise of Digital Music”.)

The music industry, realizing that the MP3 format is not going away, has embraced services like iTunes (launched by Apple in 2003 to accompany the iPod), which has become the model for legal online distribution of music. By 2011, the music industry was making more money from digital downloads than from sales of CDs and other physical media. But new developments in the music industry might now undermine what had been a decade of steady growth in digital downloads. In 2013, the fastest-growing slice of the industry’s revenue pie was made up of music subscription and streaming services like Pandora, Spotify, Grooveshark, and Last.fm. As with the advent of digital downloading of music, streaming services have generated some controversy and concern among artists and music labels, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

Records and Radio: A Rocky Relationship

We can’t discuss the development of sound recording without also discussing radio (covered in detail in Chapter 6). Though each industry developed independently of the other, radio constituted recorded sound’s first rival for listeners’ attention. This competition triggered innovations both in sound recording technology and in the business relationship between the two industries.

It all started in the 1920s, when, to the recording industry’s alarm, radio stations began broadcasting recorded music without compensating the music industry. The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), founded in 1914 to collect copyright fees for music publishers and writers, accused radio of hurting sales of records and sheet music. By 1925, ASCAP established music-rights fees for radio, charging stations between $250 and $2,500 a week to play recorded music. Many stations couldn’t afford these fees and had to leave the air. Other stations countered by establishing their own live, in-house orchestras, disseminating music free to listeners. Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, record sales continued plummeting as the Great Depression worsened.

In the early 1950s, television became popular and began pilfering radio’s programs, advertising revenue, and audience. Seeking to reinvent itself, radio turned to the record industry. Brokering a deal that gave radio a cheap source of content and record companies greater profits, many radio stations adopted a new hit-songs format—dubbed “Top 40,” for the number of records a jukebox could store. Now when radio stations aired songs, record sales soared.

In the early 2000s, though, the radio and recorded-music industries were in conflict again. Upset by online radio stations’ decision to stream music on the Internet, the recording industry began pushing for high royalty charges, hindering the development of Internet radio. The most popular online streaming services developed separately from traditional radio stations.