The Economics of Sound Recording

Sound recording is a complex business, with many participants playing many different roles and controlling numerous dimensions of the industry. Songwriters, singers, and musicians create the sounds. Producers and record labels sign up artists to create music and often own the artists’ work. Promoters market artists’ work, managers handle bands’ touring schedules, and agents seek the best royalty deals for their artist-clients.

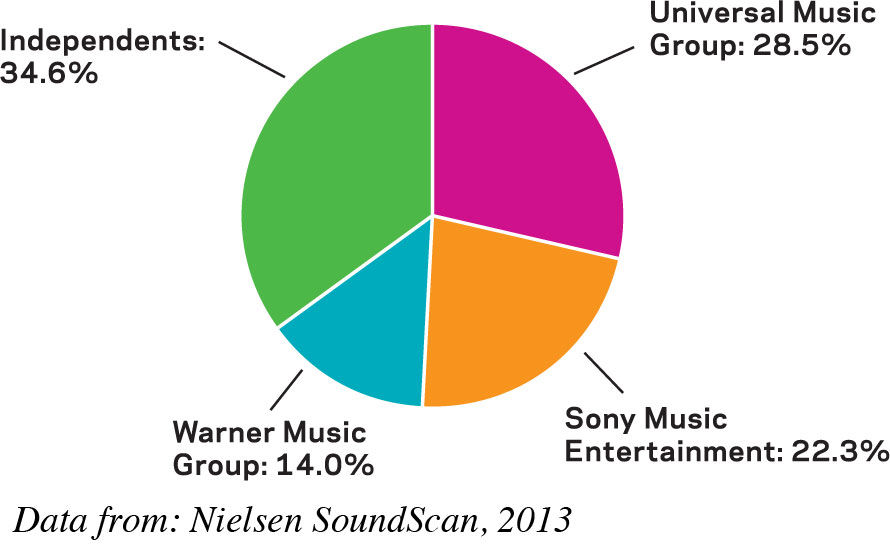

Ever since sound recording became a mass medium, there’s been a lot of money to be had from the industry—primarily through sales of records and CDs. But with the increasing amount of music available for digital download, the traditional business model has broken down. The business has also changed though consolidation. In 1998, only six major labels remained; and by 2012, that number had dwindled to three: Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group. These three companies control about 65 percent of the recording industry market in the United States, have many music stars under contract, have the resources to promote those stars, and own catalogues of recordings to sell. But despite the oligopoly (few owners exerting great control over an industry), the biggest change in the music industry has been the rising market share of independent music labels.

A Shifting Power Structure

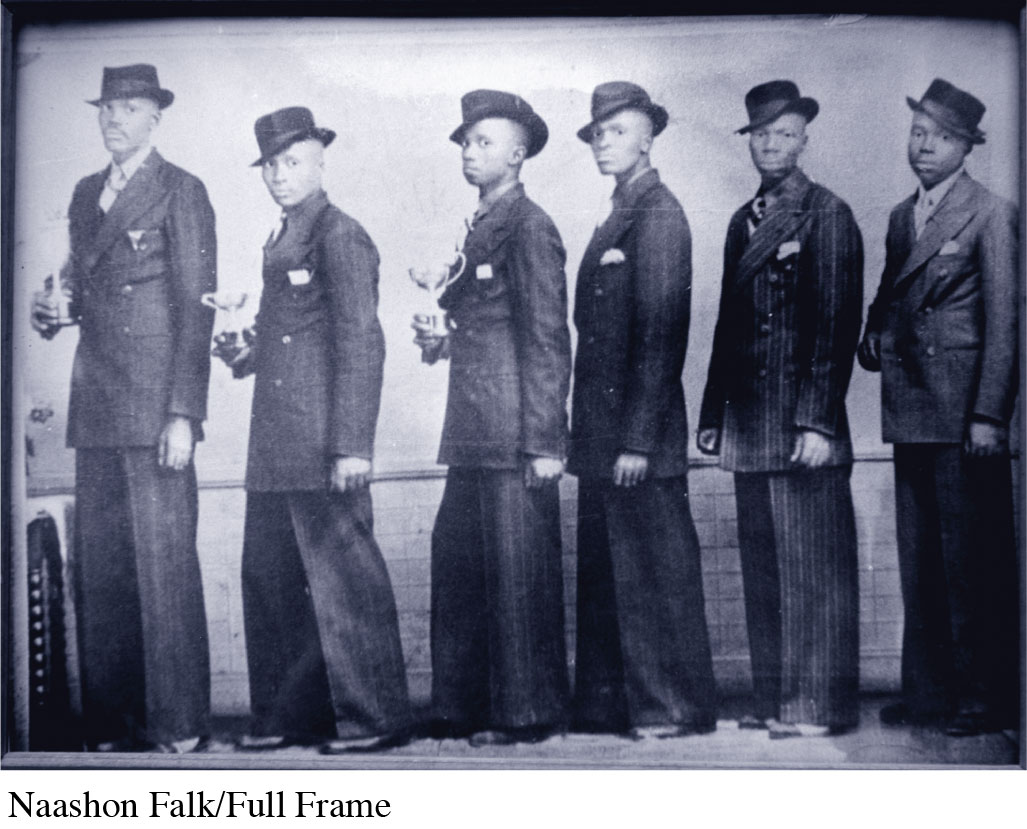

Over the years, the U.S. recording industry has experienced dramatic shifts in its power structure. From the 1950s through the 1980s, the industry consisted of numerous competing major labels as well as independent production houses, or indies. Over time, the major labels began swallowing up the indies and then buying each other. By 1998, only six big labels remained: Universal, Warner, Sony, BMG, EMI, and Polygram. That year, Universal acquired Polygram; in 2003, BMG and Sony merged; and in late 2011, EMI was auctioned off to Universal. Today, only three major music corporations exist: Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group. With their stables of stars, financial resources, and huge libraries of music to sell, these firms exert a great deal of control, at one time capturing about 85 percent of the market in the United States. Critics, consumers, and artists alike complain that this consolidation of power in the hands of a few resists new sounds in music that may not have traditional commercial appeal and supports only those major artists and styles that have large mainstream appeal. In 2013, the big three labels’ control of the U.S. market had slipped to around 65 percent. And although this is still a major portion of the market, the bigger news is that this comes as a result of recent growth in independent labels (see Figure 5.2).

The Indies Grow with Digital Music

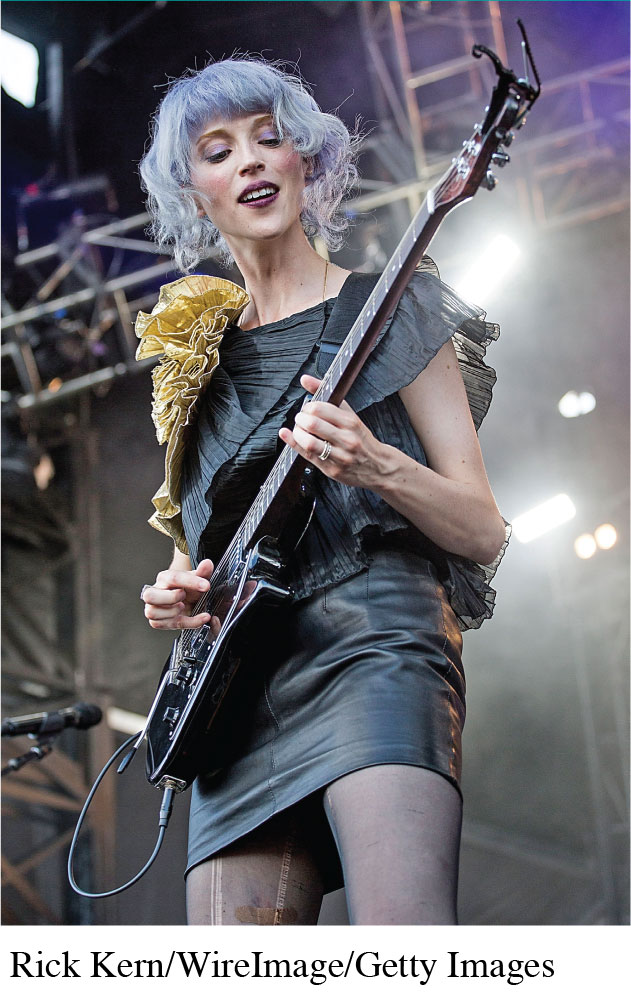

The rise of rock and roll in the 1950s and early 1960s showcased a rich diversity of independent labels—including Sun, Stax, Chess, and Motown—all vying for a share of the new music. That tradition lives on today. In contrast to the three global players, some five thousand large and small independent production houses—or indies—record less commercially viable music, or music they hope will become commercially viable. Often struggling enterprises, indies require only a handful of people to operate them. For years, indies accounted for 10–15 percent of all music releases. But with the advent of downloads and streaming, the enormous diversity of independent-label music became much more accessible, and the market share of indies more than doubled in size. Indies often still depend on wholesale distributors to promote and sell their music, or enter into deals with one of the three major labels to gain wider distribution for their artists (similar to independent filmmakers using major studios for film distribution). Independent labels have produced some of the best-selling artists of recent years: Big Machine Records (Taylor Swift, Rascal Flatts), Dualtone Records (the Lumineers), XL Recordings (Adele, Vampire Weekend), and Cash Money Records (Drake, Nicki Minaj). These companies can also release less commercially viable music or albums by established artists now ignored by the majors, who are also reluctant to invest in forgotten artists.

Making and Spending Money

Like most mass media, the recorded-music business consists of several components. Money today comes in as revenue earned mostly from sales of CDs, song downloads, and—increasingly—fees to the industry from online music subscription services. It goes out in forms such as royalties paid to artists, production costs, and distribution expenses.

Money In

In the recording industry, the product that generates revenue is the music itself. However, selling in the music business has become more challenging than ever. Revenues for the recording industry started shrinking in 2000 as file-sharing began undercutting CD sales. By 2008, U.S. music sales had fallen to $8.5 billion—down from a peak of $14.5 billion in 1999.8 CD sales fell between 2009 and 2010, as digital performance royalties increased at the same time.9 In 2011, digital sales surpassed physical CD sales in the United States for the first time. By 2013, CDs accounted for a little less than a third of total sales, with digital downloads and streaming accounting for most of the other two-thirds of the market (see Figure 5.1).

In previous decades, the primary sales outlets for music were direct-retail music stores (independents or chains such as the now-defunct Tower) and general retail outlets like Walmart, Best Buy, and Target. Another 10 percent of recording sales came from music clubs, which operated like book clubs (see Chapter 2). But almost fifteen years of dropping CD sales (in the United States at least) has meant that direct-retail music stores have largely disappeared, and big retailers typically opt for stocking only top-selling CDs rather than offering a wide variety of choices.

Conversely, digital sales—which include digital downloads from online retailers (like iTunes and Amazon), subscription streaming services (like Rhapsody and the paid version of Spotify), free streaming services (like the ad-supported Spotify, Rdio, YouTube, and Vevo), streaming radio services (like Pandora and iHeartRadio), ringtones, and synchronization fees (payments for use of music in various media, such as film, TV, and advertising)—have grown to capture almost two-thirds of the U.S. market and 39 percent of the global market.10 About 40 percent of all music recordings purchased in the United States are downloads, and iTunes is the leading retailer of downloads.

Subscription and streaming services have been a big growth area in the United States and now account for about 21 percent of U.S. music industry revenues. The difference between a streaming music service (e.g., Spotify) and streaming radio (e.g., Pandora) is that streaming music services enable listeners to stream specific songs, whereas streaming radio allows listeners to select only a genre or style of music.

Streaming Music Videos

On the Media Essentials LaunchPad, watch clips of recent music videos from Katy Perry.

Discussion: Music videos get less TV exposure than they did in their heyday, but they can still be a crucial part of major artists’ careers. How do these videos help sell Perry’s music?

The international recording industry is a major proponent of music streaming services because they are a new revenue source. Although online piracy—unauthorized online file-sharing—still exists, the advent of advertising-supported music streaming services has satisfied consumer demand for free music and weakened interest in illegal file-swapping. There are now about 450 licensed online music services worldwide.11 Spotify, one of the leading services, has more than twenty million licensed songs to stream globally, with over twenty thousand songs added every day. Spotify carries so many songs that 20 percent of its songs have never been played.12

Money Out

In the recording industry, major labels and indies must spend money to produce the product, including employing people with the right array of skills. They must also invest in the equipment and other resources essential for recording and duplicating songs and albums. The process begins with A&R (artist and repertoire) agents, who are the talent scouts of the music business. These agents work to discover, develop, and sometimes manage artists. A&R executives at the labels listen to demonstration tapes, or demos, from new artists, deciding what music to reject, whom to sign, and which songs to record.

Recording is complex and expensive. A typical recording session involves the artist, the producer, the session engineer, and audio technicians. In charge of the overall recording process, the producer handles most nontechnical elements of the session, including reserving studio space, hiring session musicians if necessary, and making final decisions about the recording’s quality. The session engineer oversees the technical aspects of the recording session—everything from choosing recording equipment to managing the audio technicians.

Dividing the Profits

The complex relationship between artists and businesspeople in the recording industry (including label executives and retailers) becomes especially obvious in the struggle over who gets how much money. To see how this works, let’s consider the costs and profits from a typical CD that retails at $18.00. The wholesale price for that CD (the price paid by the store that sells it) is about $12.50, leaving the remainder as profit for the retailer. The more heavily discounted the CD, the less profit the retailer earns. The wholesale price represents the actual cost of producing and promoting the recording plus the recording label’s profits. The record company reaps the highest profit (about $9.74 on a typical CD). But along with the artist, the record label also bears the bulk of the expenses: manufacturing costs, CD packaging design, advertising and promotion, and artists’ royalties. The actual physical product—the CD itself—costs less than 25 cents to manufacture.

New artists usually negotiate a royalty rate of 8 to 12 percent on the retail price of a CD, although more established performers might bargain for 15 percent or higher. An artist who has negotiated a typical 11 percent royalty rate would earn about $1.93 for every CD sold at a price of $17.98. So, a CD that “goes gold”—sells 500,000 units—would net the artist around $965,000. But out of this amount, artists must repay the record company the money they have been advanced to cover the costs of recording, making music videos, and touring. Artists must also pay their band members, managers, and attorneys.

The profits are divided somewhat differently in digital download sales. A $1.29 iTunes download generates about $0.40 for iTunes (iTunes gets 30 percent of every song sale) and a standard $0.09 mechanical royalty for the song publisher and writer, leaving about $0.80 for the record company. Artists at a typical royalty rate of about 15 percent would get $0.20 from the song download. With no CD printing and packaging costs, record companies can retain more of the revenue on download sales.

Another venue for digital music is streaming services like Spotify and Rdio. Some leading artists initially held back their new releases from such services due to concerns that streaming eats into their digital download and CD sales, and that the compensation from streaming services wasn’t sufficient. Spotify reports that (similar to Apple’s iTunes) it pays out about 70 percent of its revenue to music-rights holders (divided between the label, performers, and songwriters), retaining about 30 percent for itself, and that on average each stream is worth about $0.007.13 Depending on the popularity of the song, that could add up to a little or a lot of money—though even a play count of one million would still net only about $7,000. Songs played on Internet radio, like Pandora, Slacker, or iHeartRadio, have yet another formula for determining royalties. In 2000, the nonprofit group SoundExchange was established to collect royalties for Internet radio. SoundExchange charges fees of $0.002 per play, per listener.

Finally, video services like YouTube and Vevo have become sites to generate advertising revenue through music videos, which can attract tens of millions of views. For example, Beyoncé’s 2014 video for “Drunk in Love” drew more than 166 million views in just five months. There aren’t standard formulas for sharing ad revenue from music videos, but there is movement in that direction. In 2012, Universal Music Group and the National Music Publishers’ Association agreed that music publishers would be paid 15 percent of advertising revenues generated by music videos licensed for use on YouTube and Vevo.

In addition to sales royalties, there are also performance and mechanical royalties that go to various participants in the industry. A performance royalty is paid to artists and music publishers whenever a song they created or own is played in any money-making medium or venue—such as on the radio, on television, in a film, or in a restaurant. Performance royalties are collected and paid out by the three major music performance rights organizations: ASCAP; the Society of European Stage Authors and Composers (SESAC); and Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI). Songwriters also receive a mechanical royalty each time a recording of their song is sold. The mechanical royalty is usually split between the music publisher and the songwriter. However, songwriters sometimes sell their copyrights to publishers to make a short-term profit. In these cases, they forgo the long-term royalties they would have received by retaining the copyright.