The Characteristics of Contemporary Radio

Contemporary radio differs markedly from its predecessor. In contrast to the few stations per market in the 1930s, most large markets today include more than forty stations that vie for listener loyalty. With the exception of national network-sponsored news segments and nationally syndicated programs, most programming is locally produced (or made to sound like it) and heavily dependent on the music industry for content. In short, stations today are more specialized. Listeners are loyal to favorite stations, music formats, and even radio personalities, rather than to specific shows, and they generally listen to only four or five stations. About fifteen thousand radio stations now operate in the United States.

Format Specialization

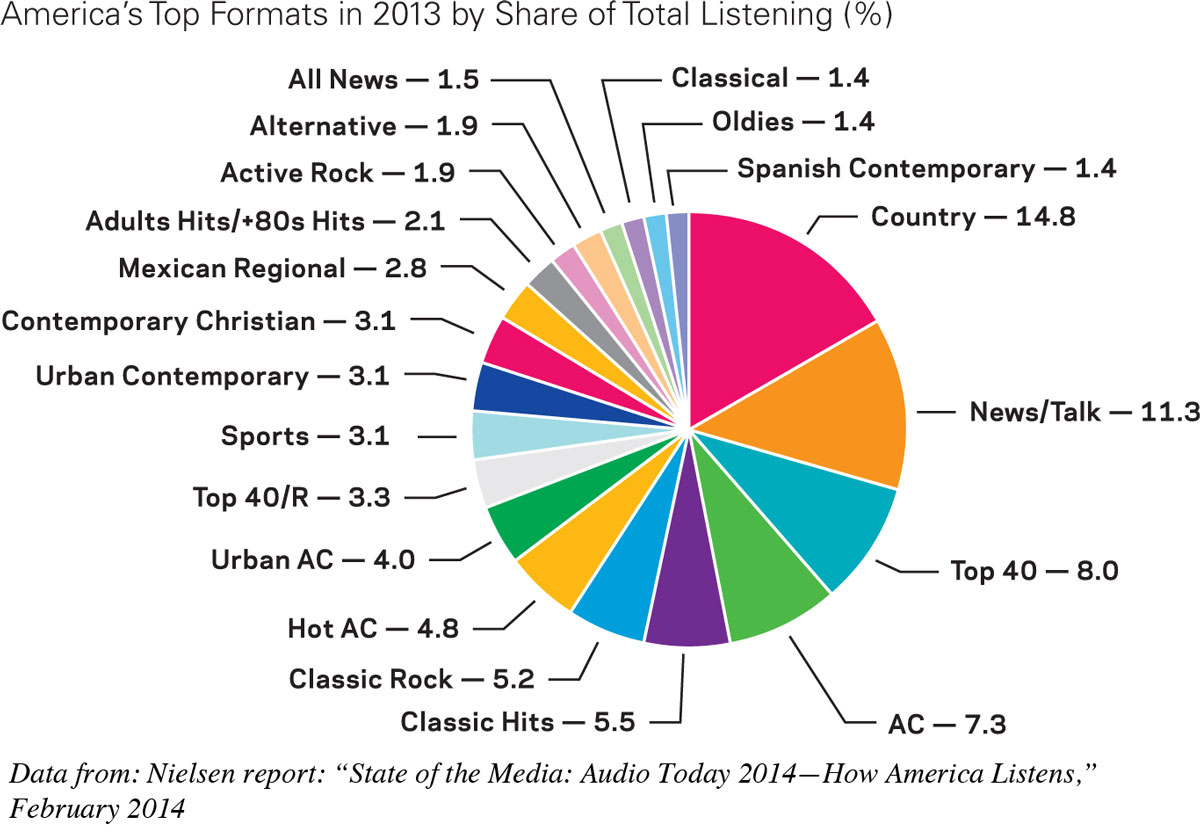

Radio stations today use a variety of formats to serve diverse groups of listeners (see Figure 6.1). To please advertisers, who want to know exactly who is listening, formats usually target audiences according to their age, income, gender, or race/ethnicity. Radio’s specialization enables advertisers to reach smaller target audiences at costs much lower than those for television. The most popular formats include the following:

Country. The most popular format in the nation (except during morning drive time, when news/talk is number one), country is traditionally the default format for small communities with only one radio station. Country music has old roots in radio, starting in 1925 with the influential Grand Ole Opry program on WSM in Nashville.

News and talk radio. As the second most popular format in the nation, news and talk radio has been buoyed by the popularity of personalities like Howard Stern, Tavis Smiley, and Rush Limbaugh. This format tends to cater to adults over age thirty-five (except for sports talk programs, which draw mostly male sports fans of all ages). Though more expensive to produce than a music format, it appeals to advertisers seeking to target working and middle-class adult consumers (see “Media Literacy Case Study: Host: The Origins of Talk Radio”).

Top 40/contemporary hit radio (CHR). Encompassing everything from rap to pop rock, this format appeals to many teens and young adults. Since the mid-1980s, however, these stations have lost ground steadily, as younger generations turned first to MTV and now to online sources for their music, rather than to radio.

Adult contemporary (AC). This format, also known as middle of the road, or MOR, is among radio’s oldest and most popular formats. It reaches about 7.3 percent of all listeners, most of them over the age of forty, with an eclectic mix of news, talk, oldies, and soft rock music. Broadcasting magazine describes AC as “not too soft, not too loud, not too fast, not too slow, not too hard, not too lush, not too old, not too new.”

Urban adult contemporary. In 1947, WDIA in Memphis was the first station to program exclusively for black listeners. This format targets a wide variety of African American listeners, primarily in large cities. Urban AC typically plays popular dance, rap, R&B, and hip-hop music (featuring performers like Rihanna and Tyga).

Spanish-language radio. One of radio’s fastest growing, this format is concentrated mostly in large Hispanic markets, such as Miami, New York, Chicago, Las Vegas, California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Besides talk shows and news segments in Spanish, this format features a variety of Spanish, Caribbean, and Latin American musical styles.

In addition, today there are other formats that are spin-offs from album-oriented rock (AOR). Classic rock serves up rock favorites from the mid-1960s through the 1980s to the baby-boom generation and other listeners who have outgrown Top 40. The oldies format originally served adults who grew up on 1950s and early 1960s rock and roll. As that audience has aged, oldies formats now target younger audiences with the classic hits format, featuring songs from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The alternative music format recaptures some of the experimental approach of the FM stations of the 1960s, although with much more controlled playlists, and has helped to introduce artists such as the Dead Weather and Cage the Elephant.

Research indicates that most people identify closely with the music they listened to as adolescents and young adults. This tendency partially explains why classic hits and classic rock stations combined have surpassed Top 40 stations today. It also helps explain the recent nostalgia for music from the 1980s and 1990s.

Nonprofit Radio and NPR

Although commercial radio dominates the radio spectrum, nonprofit radio maintains a voice. Two government rulings, both in 1948, aided nonprofit radio. Through the first ruling, the government began authorizing noncommercial licenses to stations not affiliated with labor, religion, education, or civic groups. The first license went to Lewis Kimball Hill, a radio reporter and pacifist during World War II who started the Pacifica Foundation to run experimental public stations. Pacifica stations have often challenged the status quo in both radio and government. In the second ruling, the FCC approved 10-watt FM stations. Before 1948, radio stations had to have at least 250 watts to get licensed. A 10-watt station with a broadcast range of only about seven miles took very little capital to operate, so the ruling enabled many more people to participate in radio. Many of these tiny stations became training sites for students interested in a broadcasting career.

During the 1960s, nonprofit broadcasting found a new friend in Congress, which proved sympathetic to an old idea: using radio and television as educational tools. In 1967, Congress created the first noncommercial networks: National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Under the provisions of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), NPR and PBS were mandated to provide alternatives to commercial broadcasting. With almost one thousand member stations, NPR draws thirty-two million listeners a week to popular news and interview programs like Morning Edition and All Things Considered. NPR and PBS stations rely on a blend of private donations, corporate sponsorship, and a small amount of public funding. Today, more than thirty-six hundred nonprofit radio stations operate in the United States.

Going Visual: Video, Radio, and the Web

This video looks at how radio adapted to the Internet by providing multimedia on its Web sites to attract online listeners.

Discussion: If video is now important to radio, what might that mean for journalism and broadcasting students who are considering a job in radio?

Radio and Convergence

Like every other mass medium, radio has made the digital turn by converging with the Internet. Underscoring this trend, the largest owner of radio stations across the United States changed its name from Clear Channel to iHeartMedia in September 2014, clearly inspired by its recently established iHeartRadio Internet radio service.

Interestingly, the digital turn is taking radio back to its roots in some ways. Internet radio allows for much more variety, which is reminiscent of radio’s earliest years, when nearly any individual or group with some technical skill could start a radio station. Moreover, podcasts have brought back such content as storytelling, instructional programs, and local topics of interest, which have largely been missing in corporate radio. And portable listening devices like the iPod and radio apps for the iPad and smartphones hark back to the compact portability that first came with the popularization of transistor radios in the 1950s. When we talk about these kinds of convergence, we are talking about the blurring of lines between categories. Even so, it’s still possible to identify five particular ways radio is converging with digital technologies:

Internet radio. Emerging in the 1990s with the popularity of the Web, Internet radio stations come in two types. The first involves an existing AM, FM, satellite, or HD station “streaming” a simulcast version of its on-air signal over the Web. According to StreamingRadioGuide.com, more than fifteen thousand radio stations stream their programming over the Web today.7 iHeartRadio is one of the major streaming sites for broadcast and custom digital stations. The second kind of online radio station is one that has been created exclusively for the Internet. Pandora, 8tracks, Slacker, and Last.fm are some of the leading Internet radio services. In fact, services like Pandora allow users to have more control over their listening experience and the selections that are played. Listeners can create individualized stations based on a specific artist or song that they request. AM/FM radio is used by nearly eight out of ten people who like to learn about new music, but YouTube, Facebook, Pandora, iTunes, iHeartRadio, Spotify, and blogs are among the competing sources for new music fans.8 (See “Converging Media Case Study: Streaming Music”.)

Page 205Podcasting and portable listening. Developed in 2004, podcasting (the term marries iPod and broadcasting) refers to the practice of making audio files available on the Internet so that listeners can download them to their computer and either transfer them to portable MP3 players or listen to the files from their computer. This popular distribution method quickly became mainstream as mass media companies created commercial podcasts to promote and extend existing content, such as news and reality TV, while independent producers kept pace with their own podcasts on niche topics like knitting, fly-fishing, and learning Russian. Podcasts led the way for people to listen to radio on mobile devices like smartphones. Satellite radio, Internet-only stations like Pandora and Slacker, sites that stream traditional broadcast radio like iHeartRadio, and public radio like NPR all offer apps for smartphones and touchscreen devices like the iPad, which has also led to a resurgence in portable listening. Traditional broadcast radio stations are becoming increasingly mindful that they need to reach younger listeners on the Internet, and that Internet radio is no longer tethered to a computer.

Convergence with mobile technology. For the broadcast radio industry, portability used to mean listening on a transistor or car radio. But with the digital turn to iPods and mobile phones, broadcasters haven’t been as easily available on today’s primary portable audio devices. Hoping to change that, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) has been lobbying the FCC and mobile phone industry to include FM radio capability in all mobile phones. According to the NAB, adding an FM radio chip in the manufacturing of mobile phones would cost less than a dollar and add little bulk, with the chip just the size of a nail head. In a survey, about two-thirds of mobile phone users reported they would use a built-in radio.9 The NAB argues that the radio chip would be most important for enabling listeners to access broadcast radio in times of emergencies and disasters. But the chip would also be commercially beneficial for radio broadcasters, putting them on the same digital devices as their nonbroadcast radio competitors, like Pandora.

Howard Stern’s broadcast radio show holds the record for FCC indecency fines, a fact that he and his cohost, Robin Quivers, used for material on the show. Stern avoided further indecency fines when he moved to satellite radio in 2006.© Shannon Stapleton/Reuters/Corbis

Howard Stern’s broadcast radio show holds the record for FCC indecency fines, a fact that he and his cohost, Robin Quivers, used for material on the show. Stern avoided further indecency fines when he moved to satellite radio in 2006.© Shannon Stapleton/Reuters/CorbisSatellite radio. Another alternative radio technology added a third band—satellite radio—to AM and FM. Two companies, XM and Sirius, completed their national introduction by 2002 and merged into a single provider in 2008. The merger was precipitated by their struggles to make a profit after building competing satellite systems and battling for listeners. SiriusXM offers about 165 digital music, news, and talk channels to the continental United States, with monthly prices starting at $14.49 and satellite radio receivers costing from $50 to $110. SiriusXM access is also available on mobile devices via an app. U.S. automakers (investors in the satellite radio companies) now equip most new cars with a satellite band, in addition to AM and FM, in order to promote further adoption of satellite radio. SiriusXM had more than twenty-five million subscribers by 2014.

Page 206HD radio. Approved by the FCC in 2002, HD radio is a digital technology that enables AM and FM radio broadcasters to multicast two to three additional compressed digital signals within their traditional analog frequency. For example, KNOW, a public radio station at 91.1 FM in Minneapolis–St. Paul, runs its National Public Radio news format on 91.1 HD1, BBC News on 91.1 HD2, and the BBC Mundo Spanish-language news service on 91.1 HD3. About two thousand radio stations now broadcast in digital HD.