The Economics of the Movie Business

Despite the many changes transforming the movie business, the Hollywood studio system continues to make money, whether it’s through producing movies, distributing them (through such channels as movie theaters and home-video sales), or exhibiting them (for example, in theaters or through downloads from the Internet). But to remain profitable, industry players must also invest money—in creative talent, postproduction tasks such as editing, and construction of theaters.

Money In

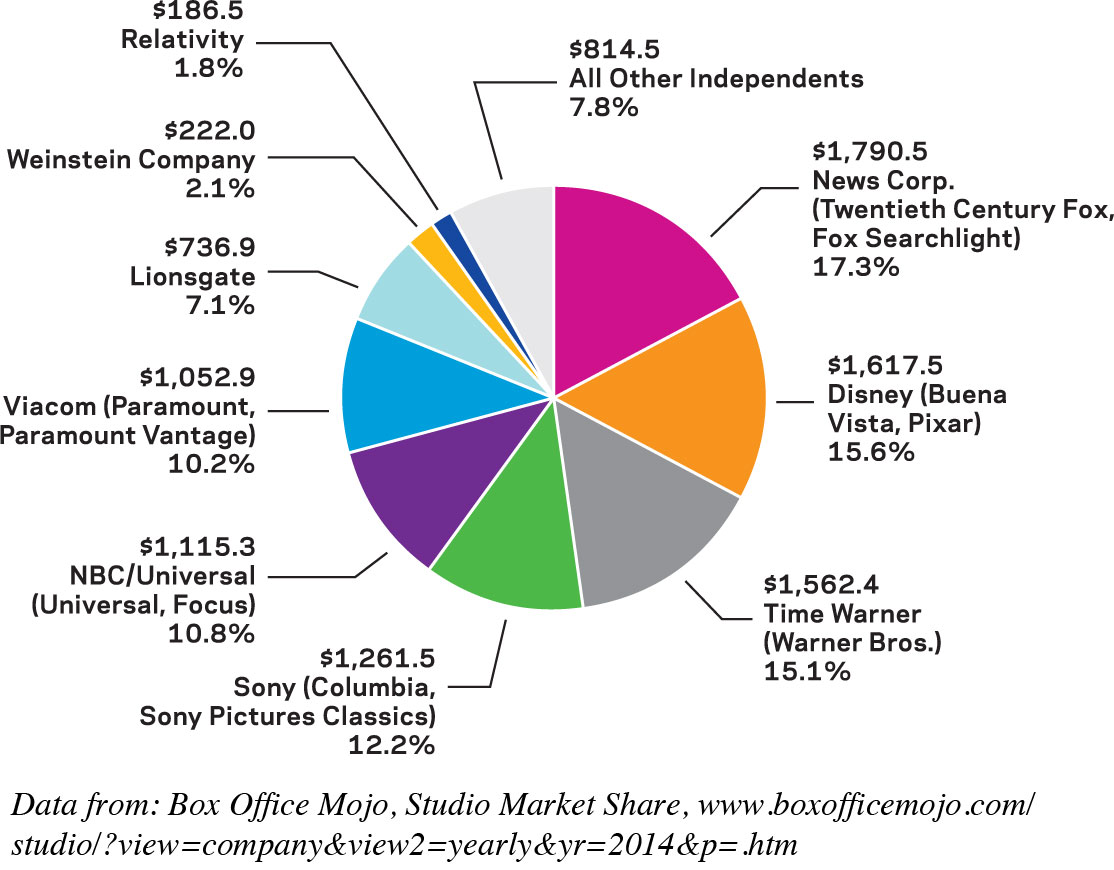

Film-industry players make money through a variety of means. In the commercial film business, these Big Six players are Warner Brothers, Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox, Universal, Columbia Pictures, and Disney—all owned by large parent conglomerates (see Figure 7.1). Together, the Big Six account for about 80 percent of the revenue generated by commercial films. They also control more than half the movie market in Europe and Asia.

Nevertheless, the cost of producing films has risen, and studios have had to find ways to generate more revenues to produce movies profitably. On top of that, with 80 to 90 percent of newly released films failing to make money at the domestic box office, studios need a couple of major hits each year to make money through one of the six main revenue sources:

Box-office sales. Studios get about 40 percent of the theater box-office take in this first “window” for movie exhibition (the theater gets the rest). Studios have recently found that they can often reel in bigger box-office receipts for 3-D films and their higher ticket prices.

DVD/video sales and rentals. Sales to the home-video market (video-on-demand, subscription streaming, Blu-ray, DVD sales and rentals) typically start about three to five months after a theatrical release and generate more revenue than domestic box-office income for major studios.

Cable and television outlets. This includes premium cable (such as HBO and Showtime), and network and basic cable showings. The syndicated TV market also pays the studios on a negotiated film-by-film basis.

Foreign distribution. Studios earn profits from distributing films in foreign markets. In fact, at $25 billion in 2013, international box-office gross revenues are more than double U.S. and Canadian box-office receipts, and they continue to climb annually, even as other countries produce more of their own films.

Independent-film distribution. Studios make money by distributing the work of independent producers and filmmakers, who hire the studios to gain wider circulation. Independents pay the studios 30–50 percent of the box-office and home-video revenue they make from their movies.

Licensing and product placement. Studios earn revenue from merchandise licensing (for example, licensing sales of action figures representing characters from a particular movie) to retailers. Companies that make cars, snacks, and other products also pay studios to place their products in movies, so that actors and characters will be shown using those products. Famous product placements include Reese’s Pieces in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Pepsi-Cola in Back to the Future II (1989), and The Lego Movie (2014)—an entire movie built around the popular toy line. The Superman movie Man of Steel (2013) reportedly features a record amount of product placement, and was singled out for Sears and IHOP logos having prominent places during big action sequences.

Synergy—the promotion and sale of a product throughout the various subsidiaries of a media conglomerate—has further driven revenues in the film industry. Companies like Disney promote not only the new movies produced by its studio division but also books, soundtracks, calendars, T-shirts, and toys based on these movies.

Money Out

Just as film-industry participants generate revenues through an array of sources, they must also spend money on various expenditures to provide the kinds of moviegoing experiences viewers want. Major expenditures include the following:

Production, including fees paid to stars, directors, and other personnel, and costs associated with special-effects technology, set design, and musical-score composition. In recent years, production costs have amounted to about 65 percent of the cost of making a movie.

Marketing, advertising, and print costs. For typical Hollywood films, these expenses can amount to 35 percent of a movie’s overall cost.4 Heavy advance promotion can double the cost of a commercial film.

Postproduction activities, such as film editing and sound recording.

Distribution expenses, such as screening a movie for prospective buyers representing theaters.

Exhibition costs, such as the significant expenses involved in constructing theaters and purchasing projection equipment.

Acquisitions. Many big studios buy up other media-related companies (such as firms making media equipment that consumers use in their homes, or enterprises providing animation services) to gain the technologies and competencies needed to stay in business. For example, Disney bought its animation partner, Pixar, in 2006, and signed a long-term distribution deal with Steven Spielberg’s DreamWorks Studios in 2009. Likewise, Time Warner’s purchase of basic and premium cable channels like TBS and HBO has enabled it to distribute its own films on cable channels for home viewing.

To cut costs, many professional filmmakers have begun seeking less expensive ways of producing movies. Digital video has become a major alternative to celluloid film, allowing filmmakers to replace expensive and bulky 16-mm and 35-mm film cameras with cheaper, lightweight digital video cameras. Digital video also lets filmmakers see the results of their camera work immediately, rather than having to wait until the film is developed. Moreover, filmmakers can capture additional footage cheaply, compared with costlier film stock and processing expenses. In fact, very few film cameras are being manufactured in the United States, as they recede in favor of the digital models.

With digital video equipment and computer-based desktop editors, people can now make movies for just a few thousand dollars—a tiny fraction of what the cost would be on film. Every year, more and more films are being made digitally. And nonprofessionals are jumping into the action—producing their own films through accessible tools such as Final Cut Pro and posting them on venues such as YouTube and Vimeo.

Convergence: Movies Adjust to the Digital Turn

The biggest challenge the movie industry faces today is the Internet. After witnessing the difficulties that illegal file-sharing brought on the music labels (some of which share the same corporate parent as film studios), the movie industry has more quickly embraced the Internet for movie distribution through outlets like Apple’s iTunes store and Netflix.

The popularity of Netflix’s streaming service (added in 2008 to its DVD-rental-by-mail service) opened the door to other similar services. Hulu—a joint venture by NBC Universal (Universal Studios), News Corp. (Twentieth Century Fox), and Disney—was created as the studios’ attempt to divert attention from YouTube and get viewers to watch free, ad-supported streaming movies and television shows online or subscribe to Hulu Plus, Hulu’s premium service. Others, such as Comcast (Xfinity TV), Google (YouTube), Walmart (Vudu), and Amazon (Amazon Instant Video), have also gotten into online digital movie distribution.

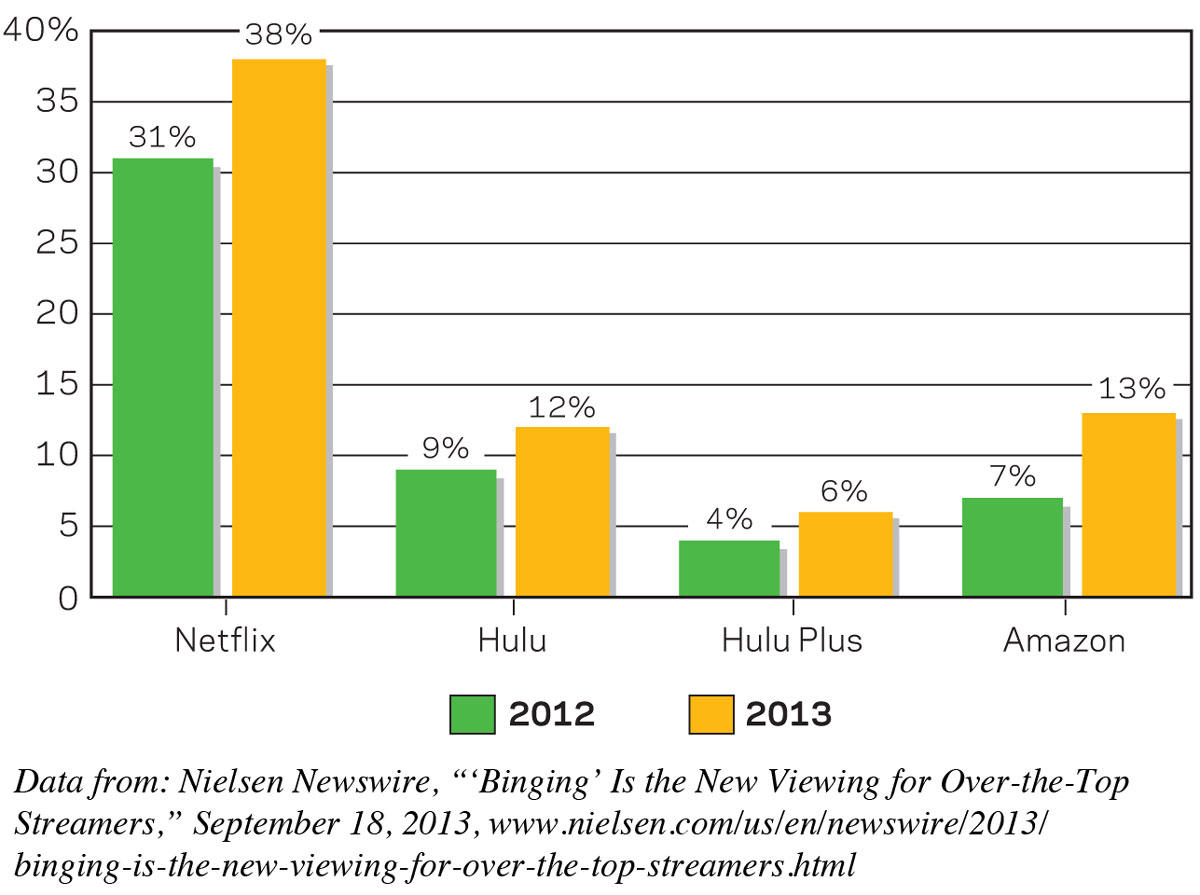

Movies are also increasingly available to stream or download on mobile phones and tablets. Several companies, including Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Google, Apple, Redbox, and Blockbuster, have developed distribution to mobile devices (see Figure 7.2).

The year 2012 marked a turning point: For the first time, movie fans accessed more movies through digital online media than physical copies, like DVDs or Blu-rays.5 For the movie industry, this shift to Internet distribution has mixed consequences. On the one hand, the industry needs to offer movies where people want to access them, and digital distribution is a growing market. On the other hand, although streaming is less expensive than producing physical DVDs, the revenue is still much lower compared to DVD sales, which had a larger impact on the major studios that had grown reliant on healthy DVD revenue.

The digital turn creates two long-term paths for Hollywood. One path is that studios and theaters will lean even more heavily toward making and showing big-budget blockbuster film franchises with a lot of special effects, since people will want to watch those on the big screen (especially IMAX and 3-D) for the full effect (see also “Converging Media: Case Study: Movie Theaters and Live Exhibition” on pages 244–245); plus, they are easy to export for international audiences. The other path features inexpensive digital distribution for lower-budget documentaries and independent films, which likely wouldn’t get wide theatrical distribution anyway, but could find an audience in those who watch at home.

The Internet has also become an essential tool for movie marketing—one that studios are finding less expensive than traditional methods, like television ads or billboards. Films regularly have Web pages, but many studios also now use a full menu of social media to promote films in advance of their release.