CONVERGING MEDIA Case Study: Movie Theaters and Live Exhibition

CONVERGINGMEDIACase StudyMovie Theaters and Live Exhibition

244

Adaptation or extinction: This Darwinian law has helped the business of movie exhibition survive into the twenty-first century. Since the arrival of the nickelodeon—the first permanent locations devoted to screening motion pictures—the exhibition branch has witnessed several profound transformations, from the development of drive-ins in the 1950s to the proliferation of multiplex screens in the 1970s and 1980s. As home viewing becomes an increasingly viable option, movie theaters are still on the lookout for opportunities to fill seats—especially on weeknights, when business is slow.

Media convergence has provided just such an opportunity. In 2011, the transition to digital cinema reached what industry analysts consider a tipping point. With more than sixty thousand screens converted to digital projection technology (roughly half the exhibition facilities worldwide), movie exhibition is taking the next step in its technological evolution: the addition of live programming. Until recently, the use of theaters for the presentation of live events was limited but not unheard of. According to legend, the Amos ‘n’ Andy radio show was so popular in the 1930s that many theaters halted their screenings for fifteen minutes to play the program over loudspeakers to the gathered audience.1 But until recently, television and radio have been the media devoted to the presentation of live events.

The repurposing of movie theaters, enabled by the conversion to digital projection, began as early as 2002, but it did not attract national attention until December 2006, when National CineMedia’s programming division, NCM Fathom, presented The Magic Flute, the first installment of its Metropolitan Opera: Live in HD series.2 Fathom now boasts a network of five hundred screens. Cinedigm, another player in this fledgling field, specializes in distributing live 3-D sporting events to its eighty-eight-theater network.3 Cinedigm’s 3-D presentation of the 2009 BCS National Championship football game sold out nineteen of the eighty theaters then in its network and generated four times the per-screen revenue of any film that night. And in 2010, more than a hundred thousand people paid $20 a ticket to watch Fathom’s live operatic broadcast of Carmen at theaters nationwide.4

macmillanhighered.com/mediaessentials3e

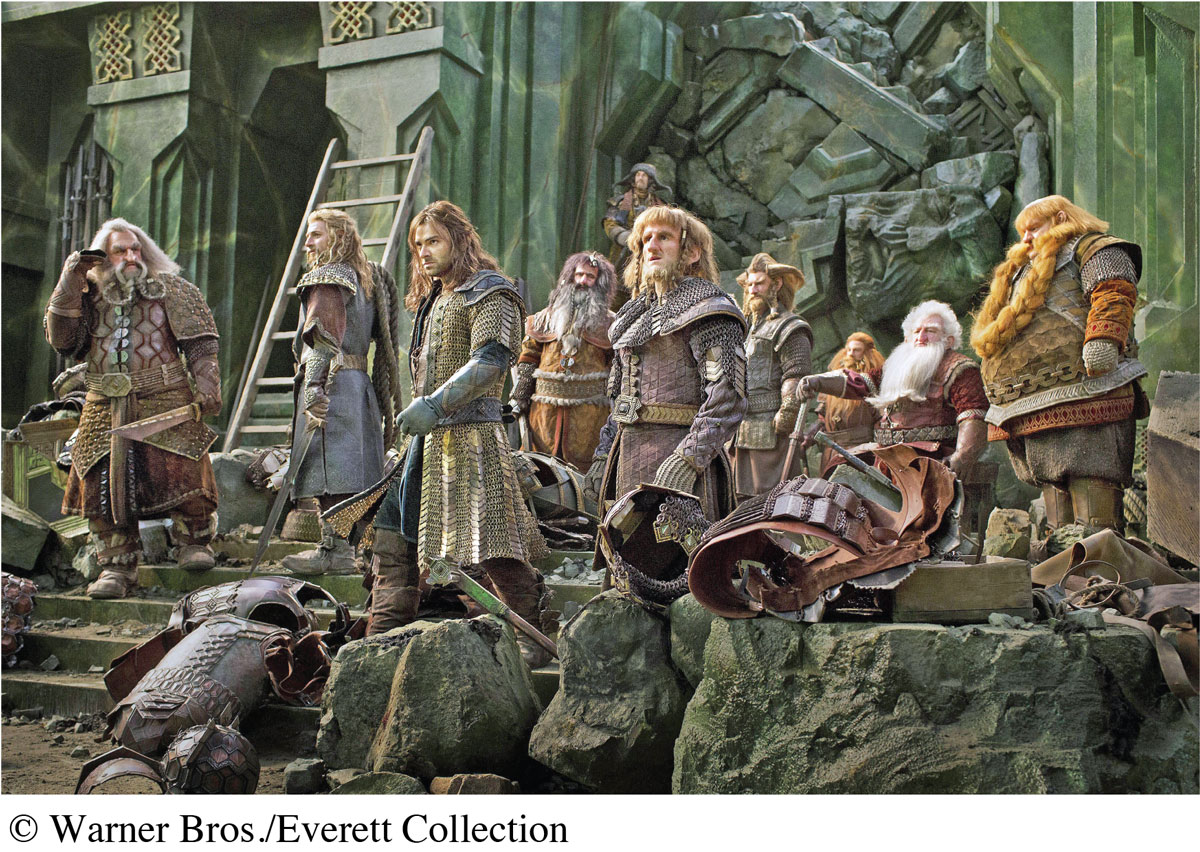

Visit LaunchPad to watch a clip from one of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit films. How might theatrical exhibition change this experience?

Visit LaunchPad to watch a clip from one of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit films. How might theatrical exhibition change this experience?

245

In addition to using this technology for sports, concerts, and opera, Fathom is also exploring and cultivating corporate and religious markets. This convergence may help movie theaters survive, even as more people opt to watch movies at home; just as audiences have a greater range of choices in how, when, and where they watch a movie, movie theaters can offer a greater range of choices in communal experiences than just new films. The movie theater of the twenty-first century could potentially be the destination for professional conventions, worship services, political rallies, and electronic gaming tournaments, as well as for watching movies in the dark with strangers. Digitizing movies for the big screen has posed additional challenges for studios. As Hollywood began making more 3-D films (the latest form of product differentiation), studios had to subsidize theater chains’ installation of new projection systems. By 2012, more than 12,620 3-D screens had been installed in theaters across the United States.5 Some theaters have also begun to experiment with high-frame-rate (HFR) projection, which Peter Jackson has championed for his trilogy of Hobbit films, and which offers images with greater clarity, particularly in 3-D.

However, the increasing number of 3-D and HFR screens isn’t always preferable. The ultra-clarity of HFR can sometimes disrupt the audience’s suspension of disbelief if the setting of the movie suddenly looks too much like a soundstage, rather than the imaginary world the filmmakers are trying to create. On the other hand, HFR technology might be a boon for live events, which tend to have a less “cinematic” look. It’s possible that whatever will be shown in movie theaters of the future won’t look much like movies as we know them today.