The Early History of Television

In 1948, only 1 percent of American households had a television set. By 1953, more than 50 percent had one, and by the early 1960s, the number had risen past 90 percent. During these early years, several major developments shaped television and helped turn it into a dominant mass medium. Others, especially an infamous scandal over corrupt TV quiz shows, brought its potential and promise into question.

Becoming a Mass Medium

Inspired by the ability to transmit audio signals from one place to another, inventors had long sought to send “tele-visual” images. For example, in the 1880s, German inventor Paul Nipkow developed the scanning disk, a large flat metal disk perforated with small holes organized in a spiral pattern. As the disk rotated, it separated pictures into pinpoints of light that could be transmitted as a series of electronic lines. Subsequent inventors improved on this early electronic technology. Their achievements pushed television from the development stage to the entrepreneurial stage and then to the mass medium stage—complete with technical standards, regulation, and further innovation (such as the move from black-and-white to color television).

The Development Stage: Establishing Patents

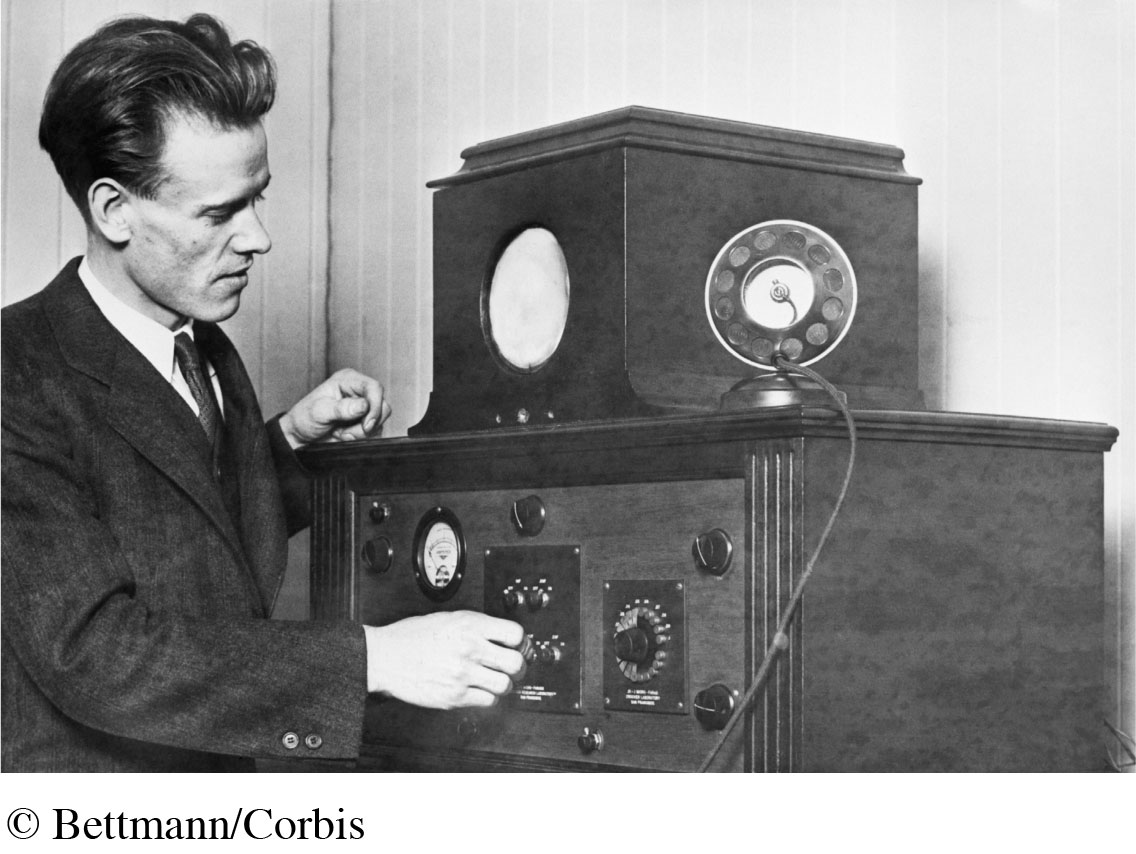

Television’s development and commercialization were fueled by a battle over patents between two independent inventors—Vladimir Zworykin and Philo Farnsworth—each seeking a way to send pictures through the air over long distances. In 1923, after immigrating to America and taking a job at RCA, the Russian-born Zworykin invented the iconoscope, the first TV camera tube to convert light rays into electrical signals. He received a patent for his device in 1928.

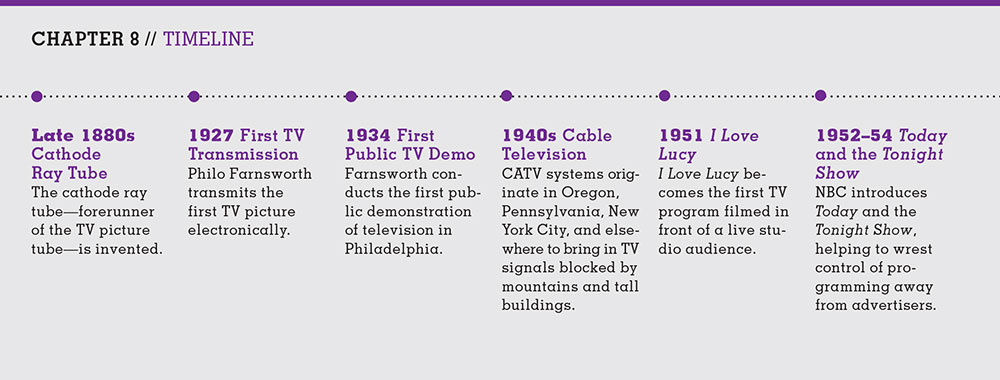

CHAPTER 8 // TIMELINE

Late 1880s Cathode Ray Tube

The cathode ray tube—forerunner of the TV picture tube—is invented.

1927 First TV Transmission

Philo Farnsworth transmits the first TV picture electronically.

1934 First Public TV Demo

Farnsworth conducts the first public demonstration of television in Philadelphia.

1940s Cable Television

CATV systems originate in Oregon, Pennsylvania, New York City, and elsewhere to bring in TV signals blocked by mountains and tall buildings.

1951 I Love Lucy

I Love Lucy becomes the first TV program filmed in front of a live studio audience.

1952–54 Today and the Tonight Show

NBC introduces Today and the Tonight Show, helping to wrest control of programming away from advertisers.

1954 Color TV Standard

RCA’s color system is approved by the FCC as the industry standard.

1958–59 Quiz-Show Scandal

Investigations into rigged quiz shows force networks to cancel twenty programs.

1960 Telstar

The first communication satellite relays telephone and television signals.

1967 PBS

The passing of the Public Broadcasting Act creates the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which establishes PBS and begins funding nonprofit radio and public TV stations.

1968 60 Minutes

CBS premieres 60 Minutes, establishing the standard for TV newsmagazines.

1975–76 Consumer VCRs

Beta and VHS videocassette recorders begin to be sold to consumers.

1975 HBO Uplinks to Satellite

The first premium channel is launched in the United States.

1976 Cable Takes Off

Ted Turner beams a signal from WTBS, his Atlanta broadcast station, creating the first superstation.

Late 1970s Franchising Frenzy

Cable companies rush to win local cable franchises across the United States.

1979 Midwest Video Case

A U.S. Supreme Court decision grants cable companies the power to select the content they carry.

1980 CNN

Ted Turner’s 24-hour news network premieres and grows to revolutionize the news business.

1981 MTV

Warner Communications launches the influential music television channel, which is acquired by Viacom in 1985.

1987 Fox Debuts

The Australian media giant News Corp. launches the Fox network, the first network launch in more than thirty-five years.

1994 DBS

The direct broadcast satellite (DBS) industry offers full-scale service, growing at a rate faster than cable.

1996 Telecom-munications Act of 1996

The act abolishes most TV ownership restrictions, paving the way for consolidation. Cable is again deregulated.

2008 Digital Streaming Boost

Netflix starts offering subscribers unlimited viewing of movies and programs in its online catalogue.

2009 Digital TV Standard

The FCC ends a TV set’s ability to receive analog broadcast signals through the airwaves with an antenna.

2013 Comcast/NBC Merger

General Electric sells control of NBC and Universal Studios to Internet giant Comcast.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

Around the same time, Farnsworth—an Idaho teenager—transmitted the first electronic TV picture by rotating a straight line scratched on a square of painted glass by 90 degrees. RCA accused Farnsworth of patent violation. But in 1930, after his high school teacher provided evidence of his original drawings from 1922, Farnsworth received a patent for the first electronic television and later licensed his patents to RCA and AT&T, which used them to commercialize the technology. He also conducted the first public demonstration of television at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia in 1934—five years before RCA’s much more famous public demonstration at the 1939 World’s Fair.

The Entrepreneurial Stage: Setting Technical Standards

Turning television into a business required creating a coherent set of technical standards for product manufacturers. In the late 1930s, the National Television Systems Committee (NTSC), a group representing engineers, inventors, network executives, and major electronics firms, began outlining industry-wide manufacturing practices and defining technical standards. In 1941, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted an analog standard (a 525-line image) for all U.S. TV sets (which at that time could show only black-and-white images). About thirty countries adopted this system, though most of Europe and Asia eventually adopted a system with slightly better image quality and resolution.

The Mass Medium Stage: Assigning Frequencies and Introducing Color

TV signals are part of the same electromagnetic spectrum that carries light waves and radio signals. In the early days of television, and before the advent of cable, the number of TV stations a city or region could support was limited because airwave frequencies interfered with one another (so you could have a Channel 5 but not a Channel 6 in the same market). In the 1940s, the FCC began assigning certain channels in specific geographic areas to prevent interference. In 1952, after years of licensing freezes due to World War II, the FCC created a national map and tried to distribute all available channels evenly throughout the country. By the mid-1950s, the nation had more than four hundred television stations in operation. Television had become a mass medium.

Television’s new status led to additional standards. In 1952, the FCC tentatively approved an experimental color system developed by CBS; however, its signal could not be received by black-and-white sets. In 1954, RCA’s color system, which sent TV images in color but allowed older sets to receive the images as black-and-white, became the color standard.

Controlling TV Content

As a mass medium, television had become big business, and broadcast networks began jockeying for increased control over its content. As in radio during the 1930s and 1940s, early television programs were developed, produced, and supported by a single sponsor—often a company, such as Goodyear, Colgate, or Buick. This arrangement gave the companies that controlled brand-name products extensive power over what was shown on television. But then newly emerging broadcast networks wanted more control and, using several strategies, set out to diminish sponsor and ad agency control.

One strategy involved lengthening program times. Sylvester “Pat” Weaver, president of NBC, took the lead. A former advertising executive used to controlling radio content for his clients, Weaver increased TV program length from fifteen minutes (standard for radio programs) to thirty minutes and even longer. This substantially raised program costs for advertisers, discouraging some from sponsoring programs.

In addition, NBC introduced two TV program types to gain more control over content. The first type—the magazine format—featured multiple segments, including news, talk, comedy, and music. These early 1950s programs—Today and the Tonight Show—are still attracting morning and late-evening audiences. By running daily rather than weekly, they made studio production costs much more prohibitive for a single sponsor. Instead of sponsoring, an advertiser paid the network for thirty- or sixty-second time slots during the show. The network, not the sponsor, now owned such programs or bought them from independent producers. In the second new program type—the “television spectacular”—networks bought programs on special topics from producers and sold ad spots to multiple advertisers. Early spectaculars (which came to be called “specials”) included decades of Bob Hope Christmas shows and the 1955 TV version of Peter Pan, which drew over sixty-five million viewers—more than triple the audience for one episode of American Idol.

Staining Television’s Reputation

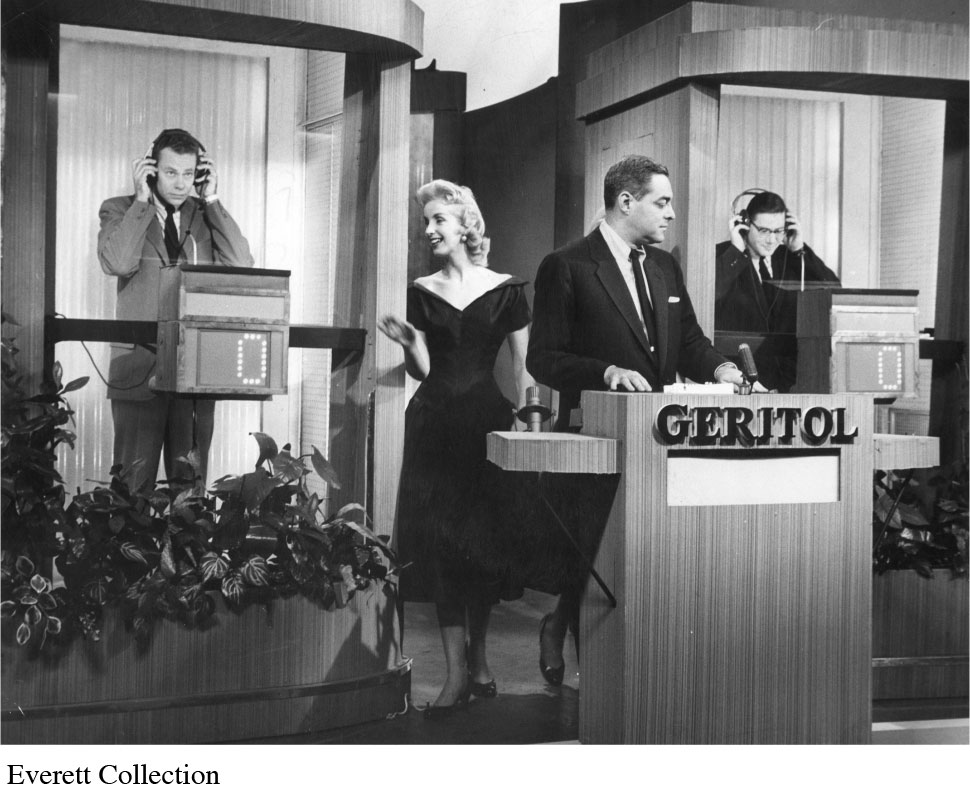

In the late 1950s, corruption in an increasingly popular TV program format—quiz shows—tainted television’s reputation and further altered the power balance between broadcast networks and program sponsors. Quiz shows had become huge business. By the end of the 1957–58 TV season, twenty-two of them aired on network television. They were (and remain) cheap to produce, with inexpensive sets and amateurs as guests. For each show, the corporate sponsor—such as Revlon or Geritol—prominently displayed its name on the set throughout the program.

But as it turned out, many quiz shows were rigged. To heighten the drama and get rid of unappealing guests, sponsors pressured TV executives to give their favorite contestants answers to the quiz questions and allow them to rehearse their responses. The most notorious rigging occurred on Twenty-One, a quiz show owned by Geritol, whose profits had climbed by a whopping $4 million a year after it began sponsoring the program in 1956.

When investigations exposed the rigging, the networks further decreased their use of sponsors to create programming. Even more important, the fraud undermined Americans’ belief in television’s democratic promise—to bring inexpensive, honest information and entertainment into every household. The scandals had magnified the separation between the privileged, powerful few (wealthy companies) and the general public. For the next forty years, the broadcast networks kept quiz shows out of prime time—the block of time (7–11 P.M. EST) with large viewer audiences.

Introducing Cable

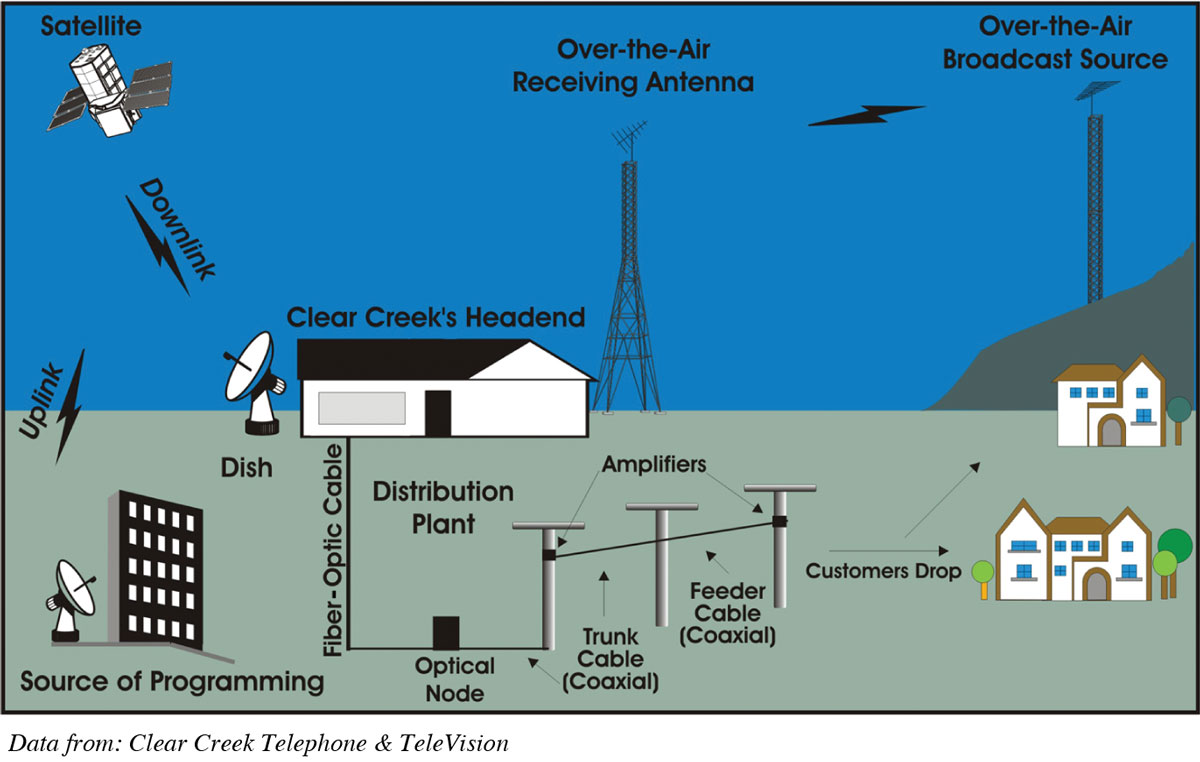

Despite the quiz-show scandals, broadcast television continued to grow in popularity in the late 1950s; however, some communities remained unable to receive traditional over-the-air TV signals, often because of their isolation or because mountains or tall buildings blocked transmission. The first small cable systems—called CATV, or community antenna television—originated in Oregon, Pennsylvania, and New York City in the late 1940s as an early attempt to solve this problem. New cable companies ran wires from relay towers that brought in broadcast signals from far away. The cable companies then strung wire from utility poles and sent the signals to individual homes, stimulating demand for TV sets in those communities.

Television Networks Evolve

Insiders discuss how cable and satellite have changed the television market.

Discussion: How might definitions of a TV network change in the realm of new digital media?

These early systems served only about 10 percent of the country and usually contained only twelve channels because of early technical and regulatory limits. Yet cable offered big advantages. First, it routed each channel in a separate wire, thereby eliminating the over-the-air interference that sometimes happened with broadcast transmissions. Second, it ran signals through coaxial cable, a core of aluminum wire encircled by braided wires that provided the option of adding more channels. Initially, many small communities with CATV received twice as many channels as were available over the air in much larger cities. Eventually, the cable industry would pose a major competitive threat to conventional broadcast television. But cable would also encounter new challenges (and opportunities) with the invention of satellite television, which uses large dishes to “downlink” signals from communication satellites in order to transmit cable TV services like HBO and CNN (see Figure 8.1).