The Evolution of Network Programming

Even with the emergence of mostly small-town cable operations, broadcast networks still controlled most TV programming in the 1950s. They began specializing in many types of programming (much of it “borrowed” from radio), including early-evening newscasts, variety shows, sitcoms, and soap operas. Eventually, additional genres and services emerged, including talk shows, newsmagazines, reality television, and public television.

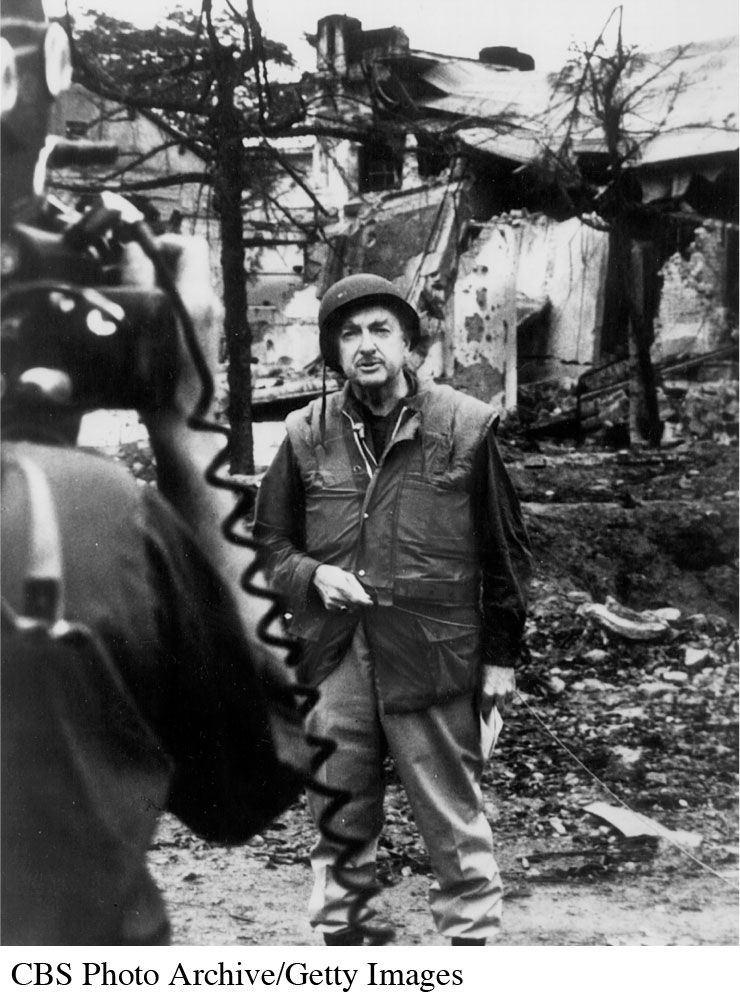

Information: Network News

Over time, many Americans abandoned their habit of reading an afternoon newspaper and began following the network evening news to catch coverage of the latest national and international events. By the 1960s, NBC, CBS, and ABC offered their thirty-minute versions of the evening news and dominated national TV news coverage until the emergence of CNN and the 24/7 cable news cycle in the 1980s. The network news divisions have been responsible for a number of milestones. The CBS-TV News, which premiered on CBS in May 1948, became in 1956 the first news show videotaped for rebroadcast in central and western time zones on affiliate stations (local TV stations that contract with a network to carry its programs; each network has roughly two hundred affiliates around the country), while NBC’s weekly Meet the Press (1947– ) remains the oldest show on television.

As with entertainment programming, the ever-broadening competition from cable and online sources of news has siphoned off network viewers. In 1980, the Big Three evening news programs had a combined audience of more than fifty million on a typical weekday evening. That audience now hovers around twenty million.1 Nonetheless, all three network newscasts often draw more viewers than do many prime-time programs.

Entertainment: Comedy

Originally, many new programs on television were broadcast live and are therefore lost to us today. The networks did sometimes manage to save early 1950s shows through poor-quality kinescopes, made by using a film camera to record live TV shows off a studio monitor (which today would be like saving a Big Bang Theory episode by shooting the TV screen in our living room with a video camera). However, the producers of I Love Lucy decided to preserve their comedy series by filming each episode, like a movie. This produced a high-quality version of each show that could be played back as a rerun. In 1956, videotape was invented, and many early comedies were preserved this way, allowing networks to create a rerun season in late spring and summer, thereby reducing the number of episodes produced each year from thirty-nine live broadcasts to about twenty-four taped programs.

In capturing I Love Lucy on film for future generations, the program’s producers understood the enduring appeal of comedy. Although a number of comedy programs and ideas were stolen from radio, television eventually developed its own history with comedy, which became a central programming strategy for both the networks and cable. TV comedy has been delivered to audiences through sketch comedy and situation comedy (sitcom).

Sketch Comedy

Most current audiences are familiar with sketch comedy thanks to NBC’s long-running Saturday Night Live (1975– ). In the early days of television, variety shows drew heavily from vaudeville-style performers, such as singers, dancers, acrobats, animal acts, stand-up comics, and ventriloquists. Typically, these shows required new ideas for sketches and other acts, with new characters and new sets, each week. This is still somewhat true of Saturday Night Live (many SNL alums have written about the all-consuming demands of working on the show), but today other sketch comedy is often pretaped and delivered without variety elements, on shows like Key and Peele and Inside Amy Schumer, which offer more diverse and specific viewpoints than the earlier mass-appeal variety shows.

Situation Comedy

In contrast, situation comedy (sitcom) is at least in some ways a simpler story form than sketch comedy. In sitcoms, you have the same characters in the same places from week to week, dealing with an increasingly complicated situation (often at home or at work), which is usually resolved in some way at the end of the half-hour program.2 From early hits like I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners to How I Met Your Mother, Modern Family, and The Big Bang Theory, the programs developed from favoring to mixing in more grounded character development. Other shows take this development further, adding more serious elements to create a dramedy. M*A*S*H was an early example of this form, which has become more common with cable shows like Louie and Weeds.

Television Drama: Then and Now

Head to LaunchPad to watch clips from two drama series: one several decades old, and one more recent.

Discussion: What kinds of changes in storytelling can you see by comparing and contrasting the two clips?

Entertainment: Drama

Television’s drama programs, which also came from radio, developed as another key genre of entertainment programming. Because production of TV entertainment was centered in New York in its early days, many of the sets, technicians, actors, and directors came from the New York theater world. Young stage actors often worked in the new television medium if they couldn’t find stage work. The TV dramas that grew from these early influences fit roughly into two categories: anthology dramas and episodic series.

Anthology Drama

Although the subject matter, style, and storytelling are very different, anthology dramas share some of the same challenges as sketch comedy. Both essentially start from scratch each week, requiring new stories, new characters, and new sets. And like the variety programs of early television, the anthology dramas of the early 1950s borrowed heavily from live theater, first with stage performances and later with teleplays (scripts written for television).

But by the 1960s, networks were moving away from anthologies. This shift was due not only to the demands of producing a completely new story each week but also to the fact that anthologies brought from the stage the tradition of dealing with heavy, complicated, and controversial topics. This increasingly contrasted with the goal of less challenging programming and also with advertising, which tended to claim products could offer quick and easy fixes to life’s problems. These factors combined to make the programs less appealing to advertisers, and thus to networks, regardless of the artistic, cultural, and social contributions anthologies could make. Despite having virtually disappeared from network television, anthology drama’s legacy continues on American public television, especially with the imported British program Masterpiece Theatre (1971– ), now known as Masterpiece Classic, Masterpiece Mystery!, and Masterpiece Contemporary.

Episodic Series

Abandoning anthologies, network producers and writers developed episodic series, first used on radio in the late 1920s. In this format, main characters continue from week to week, sets and locales remain the same, and technical crews stay with the program. Story concepts are broad enough to accommodate new adventures each week, establishing ongoing characters with whom viewers can regularly identify. Such episodic series come in two general types: chapter shows and serial programs.

Chapter shows are self-contained stories that feature a problem, a series of conflicts, and a resolution. Often reflecting Americans’ hopes, fears, and values, this structure has been used in a wide range of dramatic genres, including network westerns like Gunsmoke; medical dramas like ER and Grey’s Anatomy; police/crime network shows like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation and cable’s The Closer; family dramas like Little House on the Prairie; and fantasy/science fiction like network’s Sleepy Hollow. Serial programs are open-ended episodic shows; that is, most story lines continue from episode to episode. Among the longest-running and most familiar serial programs in TV history are daytime soap operas, which typically run five days a week and are cheaper to produce than their more prestigious prime-time counterparts, such as Scandal on ABC.

But the lines between traditionally separate chapter and serial approaches have blurred over the past two decades. Although many dramas are written to tell a more-or-less self-contained story in each episode, they also commonly incorporate serial elements, with story arcs that carry over several episodes, or even from season to season. Many dramas today somewhat resemble the television miniseries, a form that is less common now but has a notable place in broadcast television history. A miniseries typically ran during prime time over a few nights or perhaps over a week or two and then was over. Perhaps the most famous example was when ABC turned Alex Haley’s novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family into an award-winning miniseries in 1977. Current shows like HBO’s True Detective and FX’s Fargo have positioned themselves as a hybrid of miniseries and serial drama, with a season covering a full serialized story before starting over with a new (if sometimes related) set of characters in subsequent seasons.

Talk Shows and TV Newsmagazines

Many other programming genres have arisen in television’s history, both inside and outside prime time. Talk shows like the Tonight Show (1954– ) emerged to satisfy viewers’ curiosity about celebrities and politicians, and to offer satire on politics and business. Game shows like Jeopardy (which has been around in some version since 1964) provide people with easy-to-digest current events fare and history quizzes that families can enjoy together. Variety programs like the Ed Sullivan Show (1948–1971) have introduced new comedians as well as music artists, including Elvis Presley and the Beatles. TV newsmagazines like CBS’s long-running 60 Minutes usually feature three stories per episode, alternating hard-hitting investigations of corruption or political intrigue with softer feature stories about Hollywood celebrities and cultural trends.

Reality Television

Reality television dominated television from the late 1990s through much of the first decade of the twenty-first century. Inspired by MTV’s longest-running program, The Real World (1992– ), the genre’s biggest success was probably Fox’s American Idol, which was the nation’s top-rated show from 2004 to 2009. The popularity of the genre meant variations showed up on many of the niche channels up and down the broadcast and cable lineups. One could (and largely still can) find offerings ranging from network programs like The Bachelor and Celebrity Apprentice to cooking-based shows like the Food Network’s Hell’s Kitchen to backwoods shows like A&E’s Duck Dynasty.

Featuring non-actors, cheap sets, and limited scripts, reality shows (like quiz shows) are much less expensive to produce than are sitcoms and dramas. For a time, critics worried the combination of popularity with cheap overhead would spell the doom of scripted television programs (see chapter opening). However, only two reality programs made it into the 2013–14 Top 10 rated shows (Dancing with the Stars at No. 8 and The Voice at No. 10).3

Public Television

In the 1960s, public television was created by Congress to serve viewers whose interests were largely ignored by ad-driven commercial television. Much of this noncommercial television was targeted to children, older Americans, and the well educated. Under President Lyndon Johnson, Congress passed the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. The act created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which in 1969 established the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). The act led to the creation of children’s series like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Sesame Street, and Barney. Public television also broadcasts more adult fare, such as Masterpiece Theatre and other imported British programs.

In the early 2000s, despite the continued success of such staples as Sesame Street, government funding of public television was slashed. The Obama administration restored some of it, but with the rise of cable and satellite, people who have long watched PBS now often get their favorite kinds of content from sources other than network and public television. For example, the BBC—historically a major provider of British programs to PBS—also sells its shows to cable channels (including its own BBC America) and to streaming video services, such as Netflix. In 2015, Sesame Workshop reached a deal with cable channel HBO to produce more new episodes of Sesame Street, to air exclusively on HBO for six months before being provided to PBS stations for free. Though some were upset by HBO’s exclusive window, money from HBO will keep Sesame Street on the air (and at a lower cost to PBS stations) for the foreseeable future.