The Economics of Television and Cable

The economics of TV and cable differ in certain ways, as we’ll see in the pages that follow. However, like all other industries, both TV and cable must bring in revenue from specific sources and then invest that money in the business processes that are crucial to their operations.

Money In

Sources of revenue differ in some respects between TV and cable. Both broadcast network and cable programming make money from syndication, deals with online streaming services, and advertising, but only cable makes money from subscriptions—monthly fees charged to consumers for different tiers of service.

Syndication

Syndication—leasing TV stations the exclusive right to air older TV series—is a critical source of revenue for broadcast networks and cable companies. Early each year, executives from thousands of local TV stations gather at the world’s largest “TV supermarket” convention, the National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE), to acquire programs that broadcast networks (and, more recently, cable channels) have put up for syndication. Networks might make cash deals—selling shows to the highest-bidding local station—or give a program to a local station in exchange for a split in the advertising revenue—usually called a barter deal, as no money changes hands. Through this process, the stations obtain the exclusive local market rights, usually for two- or three-year periods, to network-created game shows, talk shows, and evergreens—popular reruns, such as the Andy Griffith Show, I Love Lucy, or Seinfeld. Buying syndicated programs is usually cheaper for local TV stations than producing their own programs, and it provides a familiar lead-in show to the local news.

Many local stations show syndicated programs during fringe time—immediately before the evening’s prime-time schedule and following the local evening news or the network’s late-night talk show. Syndicated shows filling these slots are either “off-network” or “first-run.” In off-network syndication, older programs that no longer run during network prime time, such as Everybody Loves Raymond, are made available as reruns to local stations, cable operators, online services, and foreign markets. First-run syndication is any non-network program specifically produced for sale only into syndication markets, such as the Oprah Winfrey Show or Wheel of Fortune.

Advertising

Advertising is another major source of revenue for the industry. TV shows live or die based on how satisfied advertisers are with the quantity and quality of the viewing audience. Since 1950, the major organization tracking and rating prime-time viewing has been Nielsen, which estimates what viewers are watching in the nation’s major markets. Ratings services provide advertisers, networks, and local stations with considerable detail about viewers—from race and gender to age, occupation, and educational background.

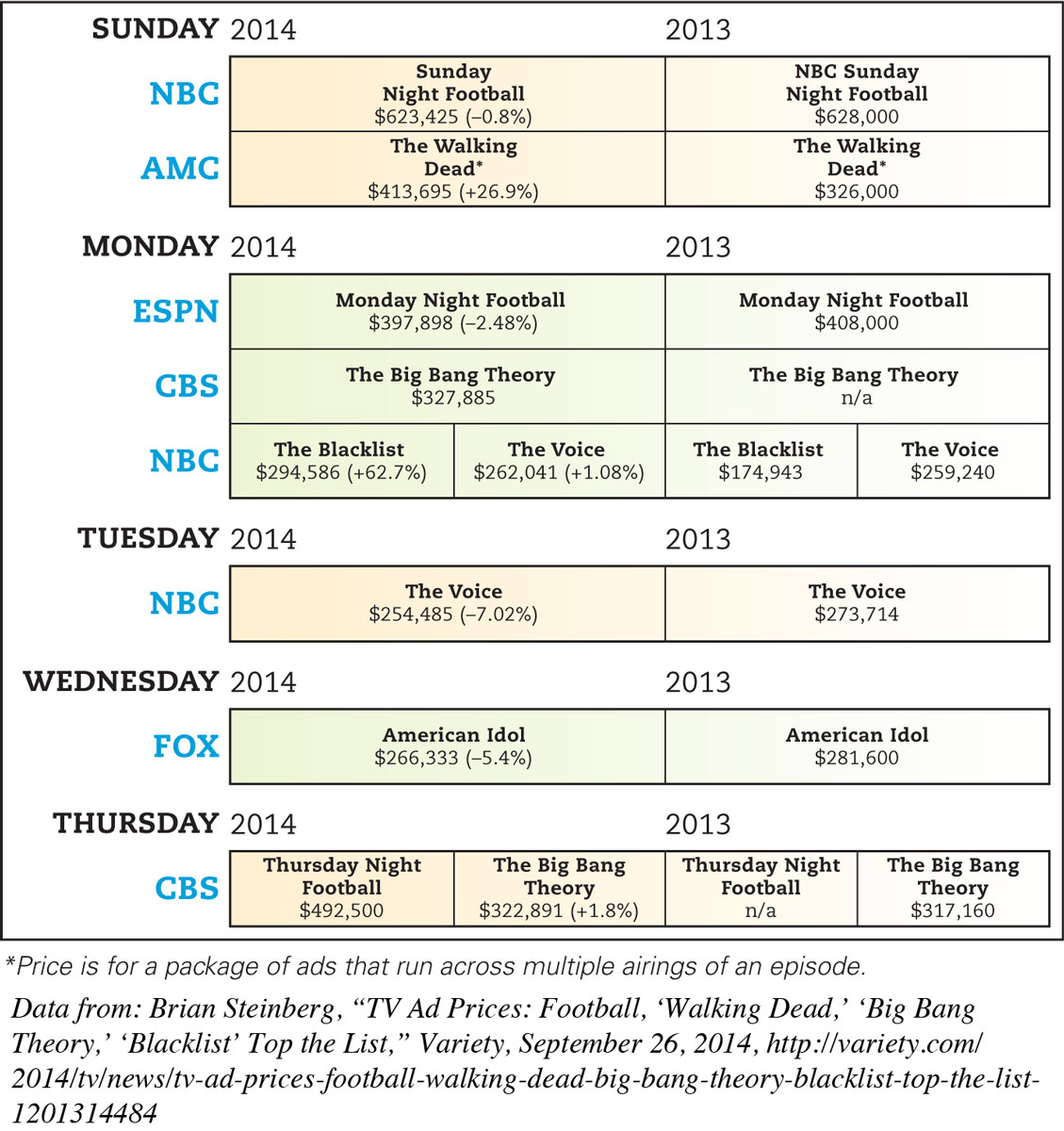

In TV measurement, a rating is a statistical estimate based on a random sample, expressed as the percentage of households tuned to a program in the total market being sampled. Another audience measure is the share, which gauges the percent of homes tuned to a program compared with those actually using their sets at the time of the sample. Prime-time advertisers want to reach relatively affluent eighteen- to forty-nine-year-old viewers, who account for most consumer spending. If a show is attracting those viewers, advertisers will compete to buy time during that program (see Figure 8.2). Traditionally, shows that did not reach enough of the “right” viewers wouldn’t attract advertising dollars and thus risked being canceled. But in the age of niche markets and Internet competition, smaller audience ratings and shares are tolerated, especially in cable programming.

Advertising also brings in money for cable. Most basic cable channels block out time for local and regional ads from, for example, restaurants, clothing stores, or car dealerships in the area. These ads are cheaply produced compared with national network ads, and they reach a smaller audience.

Subscriptions

In addition to making money from syndication, deals with streaming services, and from selling local ads, cable companies also earn revenue through monthly subscriptions for basic service, pay-per-view programming, and premium movie channels. Cable companies charge the customer a monthly fee—on average between $40 and $50 per month in 2009—and then pay cable channels like CNN and ESPN anywhere from $.35 to more than $3.00 per customer per month for these basic cable services. Whereas a cable company might pay HBO or Showtime $4 to $6 per month per subscriber to carry one of these premium channels, the company can charge each customer $10 or more per month—reaping a nice profit. Consumers also buy subscriptions to streaming sites like Netflix, which must negotiate with whomever holds the rights to the programs in order to offer them in their catalogues.

Money Out

For both TV and cable, primary costs include production (creation of programming). TV networks also invest heavily in distribution (airing of the programs they’ve created) by paying affiliate stations a fee to show their content. Cable operators distribute their programs most often by downlinking them from communication satellites and transmitting them to their various communities.

Production

Key players in the TV and cable industry—networks, cable stations, producers, and film studios—spend fortunes creating programs that they hope will keep viewers captivated for a long time. Roughly 40 percent of a new program’s production budget goes to “below-the-line” costs, such as equipment, special effects, cameras and crews, sets and designers, carpenters, electricians, art directors, wardrobe, lighting, and transportation. The remaining 60 percent covers the creative talent—or “above-the-line” costs—such as actors, writers, producers, editors, and directors. In highly successful long-running series, actors’ salary demands can drive these above-the-line costs from 60 percent to more than 90 percent.

Many prime-time programs today are developed by independent production companies owned or backed by a major film studio, such as Sony or Disney. In addition to providing and renting production facilities, these studios serve as a bank, offering enough capital to carry producers through one or more seasons. In television, after a network agrees to carry a program it’s kept on the air through deficit financing: The production company leases the show to a network for a license fee that is less than the cost of production, assuming it will recoup this loss later in lucrative rerun syndication.

To save money and control content, many networks and cable stations create their own programs, including TV newsmagazines and reality programs. For example, NBC’s Dateline requires only about half the outlay (between $600,000 and $800,000 per episode) demanded by a new hour-long drama. In addition, by producing projects in-house, the networks avoid paying license fees to independent producers.

Distribution

Whereas cable companies rely on subscriptions to fund distribution of content, the broadcast networks must pay their affiliate stations a fee to show the programs the networks have either created or licensed from independent production companies. In return for this fee, networks have the right to sell the bulk of advertising time (and run promotions of its own programs) during the shows—which helps them recoup their investments in these programs. Through this arrangement, local stations not only receive income but also get national programs that attract large local audiences to the local ad slots they retain as part of their affiliation contracts with the networks.

The networks themselves don’t usually own their affiliated stations, except in major markets like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Instead, they sign contracts with local stations (one each from the two-hundred-plus top regional TV markets) to rent time on these stations to air their network programs.

Ownership and Consolidation

Despite their declining reach and the rise of cable, the traditional networks have remained attractive business investments. In 1985, General Electric, which once helped start RCA/NBC, bought back NBC. In 1995, Disney bought ABC for $19 billion; in 1999, Viacom acquired CBS for $37 billion (Viacom and CBS split in 2005, but Viacom’s CEO remains CBS’s main stockholder). And in January 2011, the FCC and the Department of Justice approved Comcast’s purchase of NBC Universal from GE—a deal valued at $30 billion and completed in early 2013.

In the late 1990s, cable became a coveted investment, not so much for its ability to carry television programming as for its access to households connected with high-bandwidth wires. Today, there are about 5,200 U.S. cable systems, down from 11,200 in 1994. Since the 1990s, thousands of cable systems have been bought by large multiple-system operators (MSOs), corporations like Comcast and Time Warner Cable that own many cable systems. The industry for years called its major players multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) and included DBS providers like DirecTV and DISH Network. By 2014, cable’s main trade organization, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA), moved away from the MVPD classification and started using the term video subscription services, which now also includes Netflix and Hulu (see Table 8.1 above).

| Rank | Video Subscription Service | Subscribers (in millions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Netflix | 39.1 |

| 2 | Comcast Corporation | 22.4 |

| 3 | DirecTV | 20.4 |

| 4 | Dish Network Corporation | 14.0 |

| 5 | Time Warner Cable | 10.8 |

| 6 | Hulu | 6.0 |

| 7 | AT&T, Inc. | 5.9 |

| 8 | Verizon FiOS | 5.6 |

| 9 | Charter Communications, Inc. | 4.5 |

| 10 | Cox | 4.2 |

Data from: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, www.ncta.com/industry-data

Comcast, AT&T, and Time Warner

In cable, the industry behemoth today is Comcast, especially after its takeover of NBC and move into network broadcasting. Back in 2001, AT&T had merged its cable and broadband industry in a $72 billion deal with Comcast, then the third-largest MSO. The new Comcast instantly became the cable industry leader. In 2014, Comcast also owned E! Entertainment, NBCSN, the Golf Channel, Universal Studios, Fandango (the online movie ticket site), and a 32 percent stake in Hulu (with Fox and Disney). In 2014, there were about 660 companies still operating cable systems. Along with Comcast, the other large MSOs included Time Warner Cable (formerly part of Time Warner, Inc.), Cox Communications, Charter Communications, and Cablevision Systems. Comcast announced in early 2014 that it planned to buy Time Warner Cable for more than $45 billion, but dropped those plans in 2015 in the face of vocal public opposition, threats of regulatory delays, and antitrust investigations from the FCC and the Department of Justice.

DirecTV and DISH Network

In the DBS market, DirecTV and DISH Network control virtually all of the DBS service in the continental United States. In 2008, News Corp. (which owns Fox) sold DirecTV to cable service provider Liberty Media, which also owned the Encore and Starz movie channels. The independently owned DISH Network was founded as EchoStar Communications in 1980. In 2014, to counter the proposed merger talks between cable giants Comcast and TWC (later dropped), DirecTV began investigating deals with both DISH and AT&T. Over the last few years, TV services (combined with existing voice and Internet services) offered by telephone giants AT&T (U-verse) and Verizon FiOS have developed into viable competitors for cable and DBS.