The Evolution of the Internet: From Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 and Beyond

During the 1990s and early 2000s, the Internet’s primary applications were e-mail (one-to-one communication) and Web page display (one-to-many communication). By 2005, it had evolved into a far more powerful social network. In other words, the Web became a many-to-many tool, as an increasing number of applications on it led to the creation of new content and navigational possibilities for users. While doing so, it continued to change our relationship with the Internet. Through social networks, users can engage in real-time conversations with others; write, read, and comment on blogs and wikis; share photos and videos; and interact within virtual 3-D environments. People commonly describe these first two phases in the Internet’s evolution as Web 1.0 and Web 2.0, even as elements of Web 3.0 (or the Semantic Web) become more common.

Web 1.0

Internet use before the 1990s mostly consisted of people transferring files, accessing computer databases from remote locations, and sending e-mails through an unwieldy interface. The World Wide Web (or the Web) changed all of that. Developed in the late 1980s by software engineer Tim Berners-Lee at the CERN particle physics lab in Switzerland to help scientists better collaborate, the Web enabled users to access texts through clickable links rather than through difficult computer code. Known as hypertext, the system allowed computer-accessed information to associate with, or link to, other information on the Internet—no matter where it was located. HTML (HyperText Markup Language), the written code that creates Web pages and links, can be read by all computers. Thus, computers with different operating systems (Windows, Macintosh, Linux) can communicate easily through hypertext. After CERN released the World Wide Web source code into the public domain in 1993, many people began to build software to further enhance the Internet’s versatility.

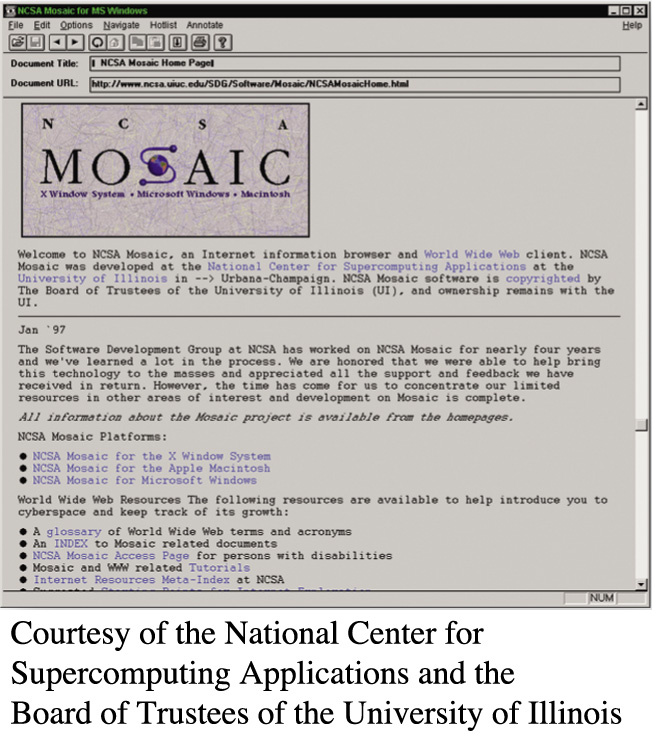

The release of Web browsers—software applications that help users navigate the Web—brought the Web to mass audiences for the first time. Computer programmers led by Marc Andreessen at the University of Illinois (a supercomputer center that was part of NSFNET) released Mosaic in 1993, the first user-friendly browser to load text and graphics together in a magazine-like layout. With its attractive fonts and easy-to-use navigation buttons, Mosaic was a huge improvement over previous technology. In 1994, Andreessen joined investors in California’s Silicon Valley to introduce another major advance—a commercial browser called Netscape. Together, the World Wide Web, Mosaic, and Netscape gave the Internet basic multimedia capability, enabling users to transmit pictures, sound, and video.

Web 2.0

The shift to Web 2.0 encouraged a deeper trend toward media convergence: different types of content (video, text, audio) created by all sorts of sources (users, corporations, nonprofit organizations) coming together and accessed on a variety of devices (personal computers, smartphones, tablets). Whereas the Internet was primarily a medium for computer-savvy users to deliver text-and-graphic content during its Web 1.0 stage, it has been transformed into a place where people can access and share all manner of media content: music on Spotify, video on YouTube, journalism on Blogspot, eBooks on Amazon, mountains of collective intelligence on Wikipedia, gossip on Twitter, and relationships on Facebook. Whereas the signature products of Web 1.0 were increased content access and accompanying dot-com consumerism, the iconic achievement of Web 2.0 is social networking.

Types of Social Media

In less than a decade, a number of different types of social media have evolved, with multiple platforms for the creation of user-generated content. European researchers Andreas M. Kaplan and Michael Haenlein identify six categories of social media on the Internet: social networking sites, blogs, collaborative projects, content communities, virtual game worlds, and virtual social worlds.4

Social Networking Sites

Social networking sites—including Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumbler, and Pinterest—have become among the most popular places on the Internet. The largest of these sites, Facebook, started at Harvard in 2004 as an online substitute to the printed facebooks the school created for incoming first-year students. Ten years later, it had become a global phenomenon, with over a billion active users and available in more than seventy languages. Facebook empowers users to create personal profiles; upload photos; create lists of their favorite movies, books, and music; and post messages to connect with old friends and meet new ones. A subcategory of social networking sites contains sites more specifically devoted to professional networking, such as LinkedIn. The popularity of social media combined with an explosion in mobile devices has altered our relationship with the Internet. Two trends are noteworthy: (1) Apple now makes more than five times as much money selling iPhones, iPads, iPods, and accessories as it does selling computers, and (2) the number of Facebook users (1.23 billion in 2014) keeps increasing. The significance of these two trends is that through our Apple devices and Facebook, we now inhabit a different kind of Internet—what some call a closed Internet or a walled garden.5

In the world in which the small screens of smartphones are becoming the preferred medium for linking to the Internet, we don’t typically get the full open Internet, one represented by the vast searches brought to us by Google. Instead, we get a more managed Internet, brought to us by apps or platforms that carry out specific functions via the Internet. Are you looking for a nearby restaurant? Don’t search on the Internet—use this app especially designed for that purpose. The distributors of these apps act as gatekeepers; Apple has more than 1.15 million apps in its App Store, and Apple approves every one of them. The competing Android app stores on Google Play and Amazon have a similar number of apps (with many fewer apps in the Windows Store), but Google and Amazon exercise less control over approval of apps than Apple does.

Blogs

Years before there were status updates or Facebook, blogs (short for Weblogs) enabled people to easily post their ideas to a Web site. Popularized with the release of Blogger (now owned by Google) in 1999, blogs contain articles or posts in chronological, journal-like form, often with reader comments and links to other sites. Blogs can be personal or corporate multimedia sites, sometimes with photos, graphics, podcasts, and video. Some blogs have developed into popular news and culture sites, such as the Huffington Post, TechCrunch, Mashable, Gawker, HotAir, ThinkProgress, and TPM (Talking Points Memo).

Some blogs are simply an individual’s online journal or personal musings. Others provide information, analysis, or commentary that isn’t presented in the more traditional news media. Although some are written by journalists, the vast majority of the Web’s approximately 200 million blogs are written by individuals who don’t use established editorial practices to check their facts.

Some of the leading platforms for blogging include Blogger, WordPress, Tumblr, Weebly, and Wix. But by 2013, the most popular form of blogging was microblogging, with about 241 million active users on Twitter, sending out 500 million tweets (a short message with a 140-character limit) per day.6 In 2013, Twitter introduced an app called Vine that enabled users to post short video clips. A few months later, Facebook’s Instagram responded with its own video-sharing service.

Collaborative Projects

Probably the most common examples of projects in which users build something together, often with anyone able to edit or add information, are Web sites called wikis (wiki means “quick” in Hawaiian). Large wikis include Wikitravel (a global travel guide); Wikimapia (combining Google Maps with wiki comments); and, of course, Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia that is constantly being updated by interested volunteers.

Although Wikipedia has become one of the most popular resources on the Web, some people have expressed concern that its open editing model compromises its accuracy.7 When accessing any wiki, the user may not know for certain who has contributed which parts of the information found there, who is changing the content, and what the contributors’ motives are. (For example, politicians and other well-known individuals who are particularly concerned about their public image may distort information in their Wikipedia entries to improve their image—or their supporters may do the same.) This worry has led Wikipedia to lock down topic pages that are especially contested, which has inevitably led to user protests about information control. At the same time, Wikipedia generally offers a vibrant forum where information unfolds, debates happen, and controversy over topics can be documented. And just like a good term paper, the best Wikipedia entries carefully list their sources, allowing a user to dig deeper and have some way of judging the quality of information in a given listing.

But wikis aren’t the only way in which Internet users collaborate. Kickstarter is a popular fund-raising tool for creative projects such as books, recordings, and films. InnoCentive is a crowd-sourcing community that offers award payments for people who can solve business and scientific problems. And Change.org has become an effective petition project to push for social change. For example, in 2014, Lucien Tessier of Maryland began a campaign to petition the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) to drop its ban against openly gay Scouts. Nearly 130,000 people signed the Change.org petition, and after additional lobbying, the BSA dropped its ban on gay Scouts under the age of eighteen.8

Content Communities

Content communities are the best examples of the many-to-many ethic of social media. Content communities exist for the sharing of all types of content, from text (Fanfiction.net) to photos (Flickr, Photobucket) and videos (YouTube, Vimeo). YouTube, created in 2005 and bought by Google in 2006, is the most well-known content community, with hundreds of millions of users around the world uploading and watching amateur and professional videos. YouTube gave rise to the viral video—a video that becomes immediately popular by millions sharing it through social media platforms. The most popular video of all time—a fifty-six-second home video titled “Charlie bit my finger—again!” had more than 815 million views as of April 2015. By 2014, YouTube reported that one hundred hours of video are uploaded to the site every minute, and it has more than one billion unique users each month.

Virtual Game Worlds and Virtual Social Worlds

Virtual game worlds (covered in greater detail in Chapter 10) and virtual social worlds invite users to role-play in rich 3-D environments, in real time, with players throughout the world. In virtual game worlds (also known as massively multiplayer online role-playing games, or MMORPGs) such as World of Warcraft and Elder Scrolls Online, players can customize their online identity, or avatar, and work with others through a game’s challenges. Community forums for members extend discussion and shared play outside the game. Virtual social worlds, like Second Life, enable players to take their avatars through simulated environments and even make transactions with virtual money.

The Internet in 1995

In a clip from the 1995 thriller The Net, Sandra Bullock’s character communicates using her computer.

Discussion: How does this movie from over two decades ago portray online communication? What does it get right, and what seems outdated now?

Social networking sites have given a huge boost to one-to-many communication. However, they’ve also raised some thorny privacy questions: Should we post highly personal information about ourselves, including pictures and messages about our political views? (Potential—or current—employers routinely visit these sites to examine job candidates’ or employees’ profiles.) Should information in our profiles be considered public for some eyes but off-limits to others?

Web 3.0: The Semantic Web

Although we have drawn a relatively clear line between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0, the boundaries between 2.0 and 3.0 are fuzzier. But hypertext inventor Tim Berners-Lee and two coauthors published an influential article in Scientific American in which they described a “Semantic Web.” Semantics is the study of meaning, so a Semantic Web refers to a more meaningful—or organized—Web. Essentially, this involves a continuing evolution in our relationship with the Internet, more than just major changes in what is on the Internet. Berners-Lee and his colleagues explain, “The Semantic Web is not a separate Web but an extension of the current one, in which information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in cooperation.”9

The best example of the Semantic Web is Apple’s voice recognition assistant, Siri, first shipped with its iPhone 4S in 2011. Siri uses conversational voice recognition to answer questions, find locations, and interact with various iPhone functionalities, such as the calendar, reminders, the weather app, the music player, the Web browser, and the maps function. Some of its searches get directed to Wolfram Alpha, a computational search engine that provides direct answers to questions, rather than the traditional list of links for search results. Other Siri searches draw on the databases of external services, such as Yelp! for restaurant locations and reviews, and StubHub for ticket information. Another example is the Siemens refrigerator (available in Europe) that takes a photo of the interior every time the door closes. The owner may be away at the supermarket but can call up a photo of the interior to be reminded of what should be on the shopping list.10