The Internet in a Democratic Society

Despite concerns over some online content, many tout the Internet as the most democratic social network ever conceived. But this same medium has also presented threats to our democracy—in the form of a division between people who can afford to use the Internet and those who can’t, and the Internet’s increasing commercialization.

Access: Closing the Digital Divide

Coined to echo the term economic divide (the disparity of wealth between the rich and the poor), the term digital divide refers to the contrast between the information haves (those who can afford to pay for Internet services) and the information have-nots (those who can’t).

Although about 87 percent of U.S. households are connected to the Internet, there are big gaps in access. For example, a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center found that only 57 percent of Americans over the age of sixty-five go online, compared with 88 percent of Americans ages fifty to sixty-four, 93 percent of Americans ages thirty to forty-nine, and 97 percent of Americans ages eighteen to twenty-nine. Education has an even more pronounced effect: Only 76 percent of people with a high school education or less have Internet access, compared with 91 percent of people with some college and 97 percent of college graduates.18

The rising use of smartphones is helping to narrow the digital divide, particularly along racial lines. In the United States, African American and Hispanic families have generally lagged behind whites in home access to the Internet, which requires a computer and broadband access. However, another Pew Research Center survey reported that African Americans and Hispanics are active users of mobile Internet devices. Thus, the report concluded, “While blacks and Latinos are less likely to have access to home broadband than whites, their use of smartphones nearly eliminates that difference.”19

318

320

Other ways of bridging the digital divide include greater public access through libraries and other public facilities, and for cities and other municipalities to offer inexpensive Wi-Fi—wireless Internet access—which enables users of laptops, tablets, and other devices to connect to the Internet wherever they are.

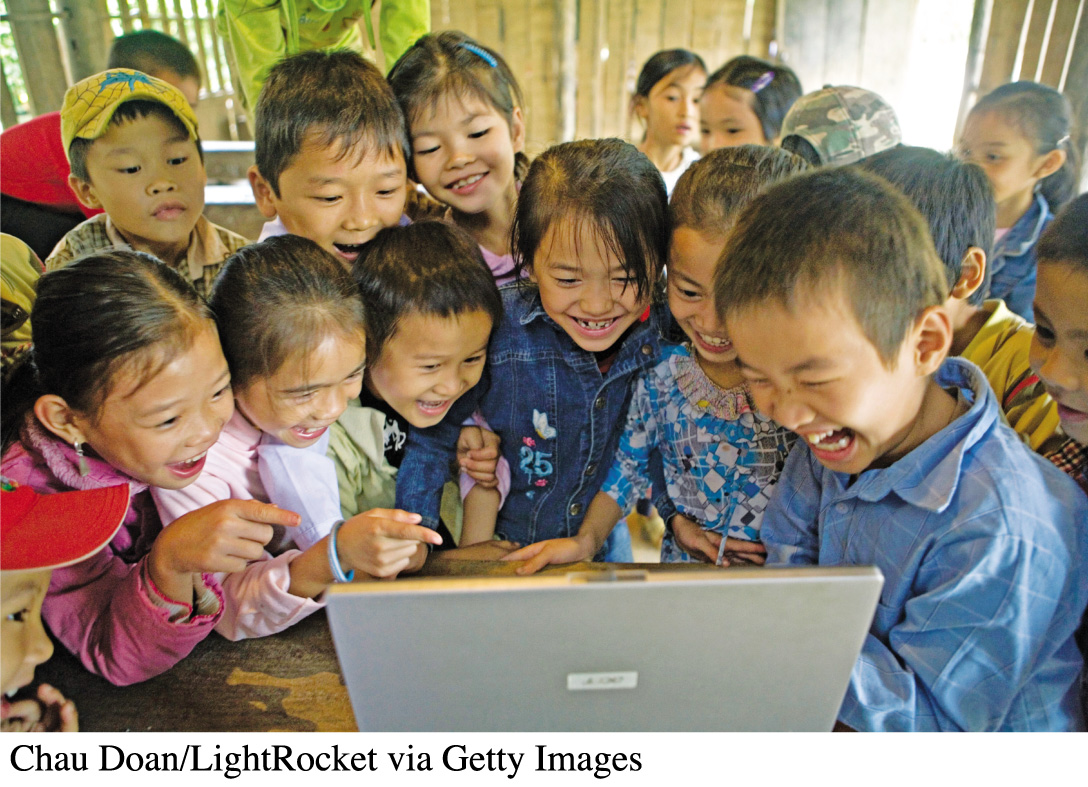

Globally, though, the have-nots face an even greater obstacle in crossing the digital divide. Although the Web claims to be worldwide, the most economically powerful countries—such as the United States, Sweden, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the United Kingdom—account for much of its activity and content. In nations such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Myanmar (Burma), the government permits limited or no access to the Web. In other countries, an inadequate telecommunications infrastructure hampers access to the Internet. And in underdeveloped countries, phone lines and computers are almost nonexistent. For example, in Sierra Leone—a nation of about six million people in western Africa, with poor public utilities and intermittent electrical service—only about ten thousand people (about 0.16% of the population) are Internet users.20 However, as mobile phones become more popular in the developing world, they could provide one remedy to the global digital divide.

Ownership and Customization

Some people have argued that the biggest threat to democracy on the Internet is its increasing commercialization (see “Media Literacy Case Study: Net Neutrality” on pages 306–307). Similar to what happened with radio and television, the growth of commercial “channels” on the Internet has far outpaced the emergence of viable nonprofit channels, as a few corporations have gained more control over this medium. Although there was much buzz about lucrative Internet start-ups in the 1990s, it was the largest corporations (Microsoft, Yahoo!, Google) that weathered the crash of the dot-coms in the early 2000s and maintained their dominance.

macmillanhighered.com/mediaessentials3e

The Rise of Social Media

Media experts discuss how social media are changing traditional media.

Discussion: Some consider the new social media an extension of the very old oral form of communication. Do you agree or disagree with this view? Why?

As we’ve seen, the Internet’s booming popularity has tempted commercial interests to gain even more control over the medium. It has also sparked debate between defenders of the digital age and those who want to regulate the Net. Defenders argue that newer media forms—digital music files, online streaming of films and TV shows, blogs—have made life more satisfying and enjoyable for Americans than has any other medium. Further, they maintain that mass customization, whereby individual consumers can tailor a Web page or other media form, has enabled us to express our creativity more easily and conveniently than ever. For example, if we use a service like Facebook, we get the benefits of creating our own personal Web space without having to write the underlying code. On the other hand (dissenters point out), we’re limited to the options, templates, and automated RSS feeds provided by the media company. So (the dissenters ask), how free are we, really, to express our true creative selves? And how much are we being controlled by the big Internet firms?

321

322