Chapter Introduction

CHAPTER 12

Solid and Hazardous Waste Management

Central Question: How can we reduce the environmental impact of solid waste and dispose of hazardous waste safely?

SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Describe the types of solid and hazardous waste.

ISSUES

ISSUES

Explain the problems that arise from disposing and storing solid and hazardous waste.

SOLUTIONS

SOLUTIONS

Analyze the tactics for dealing with solid and hazardous waste.

Philadelphia’s Traveling Trash

One city’s refuse changed the way the world deals with garbage.

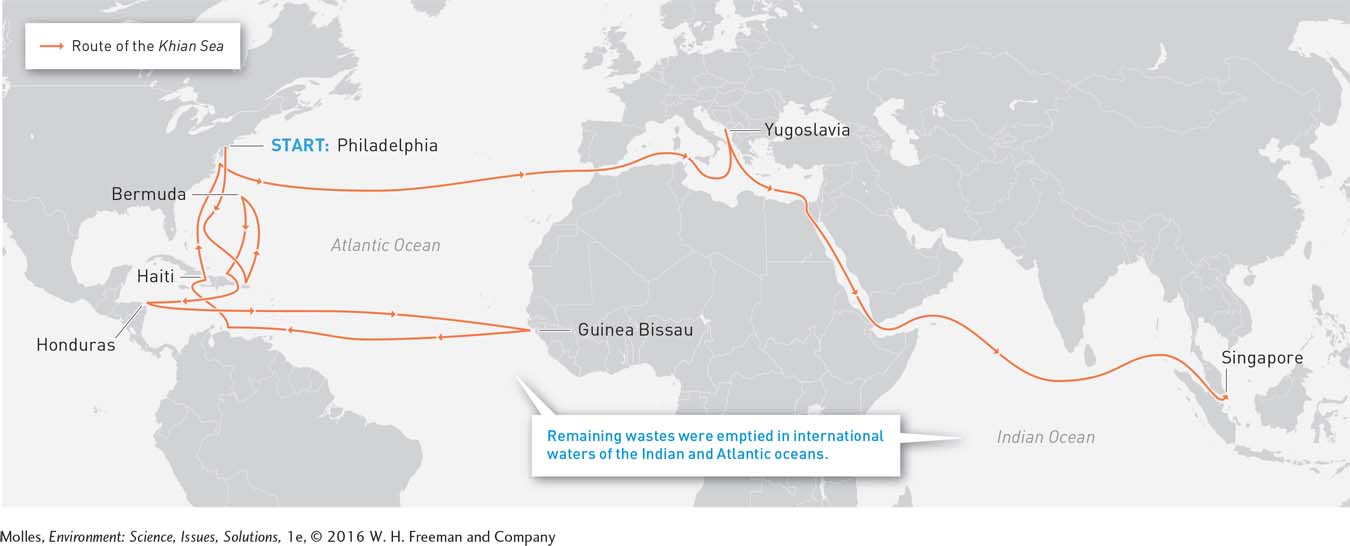

In the 1970s, Philadelphia had a serious trash problem. Its dumps were filled to maximum capacity and the city started sending its paint cans, car tires, watermelon rinds, and disposable diapers to New Jersey and other neighboring states. After New Jersey stopped accepting such waste in 1984, city officials were paying to have their trash hauled to places as far away as Houston, Texas. To reduce soaring costs, Philadelphia started burning its waste. Though incineration decreases waste volume by 70% or more, it leaves behind ash laden with toxic agents that must be safely stored somewhere. So Philadelphia came up with a plan: In 1986 a barge named the Khian Sea was piled with 15,000 tons of Philadelphia’s incinerated trash. Khian Sea would carry the ash to the Bahamas, where it would be dumped on a man-

Next, the Khian Sea tried the Dominican Republic. No luck there, either. The ship was also turned away by Honduras, Panama, Bermuda, Guinea Bissau, and the Dutch Antilles. In Haiti, the crew unloaded some 4,000 tons of the ash, claiming it was “topsoil fertilizer.” By the time the Haitian government was alerted to the true nature of the material, the barge had departed.

The Khian Sea sailed onward, crossing the Atlantic, passing through the Suez Canal, and drifting into Southeast Asia. Despite changing the name and registration of the ship twice in order to conceal its identity, no country would allow the foul ash to be unloaded onto its shores. After a final attempt at Singapore, the barge reversed course, crossed the Indian Ocean, and dumped its toxic load into international waters—

“There is no ‘waste’ in nature and no ‘away’ to which things can be thrown.”

Barry Commoner, second law of ecology

The global reaction to the Khian Sea incident and others would contribute to the development of an international treaty known as the Basel Convention, discussed later in this chapter. The bottom line is that the problem of how to safely handle refuse touches every person and every community on Earth. Shrinking landfill space, rising waste disposal costs, incinerating waste, and exporting hazardous waste are challenges we still face today.

Prior to the environmental movement of the 1970s, relatively little regulation existed regarding the disposal and treatment of solid waste. Dump sites created before environmental legislation might be undocumented and contain hazardous waste, which might leach into the soil. Moving into the future, we need to recycle as much as we can and limit the amount of nonrecyclable waste produced, while ensuring that it is treated and contained safely. These goals lead to the central question of this chapter.

Central Question

How can we reduce the environmental impact of solid waste and dispose of hazardous waste safely?