12.5 New forms of hazardous waste are on the rise

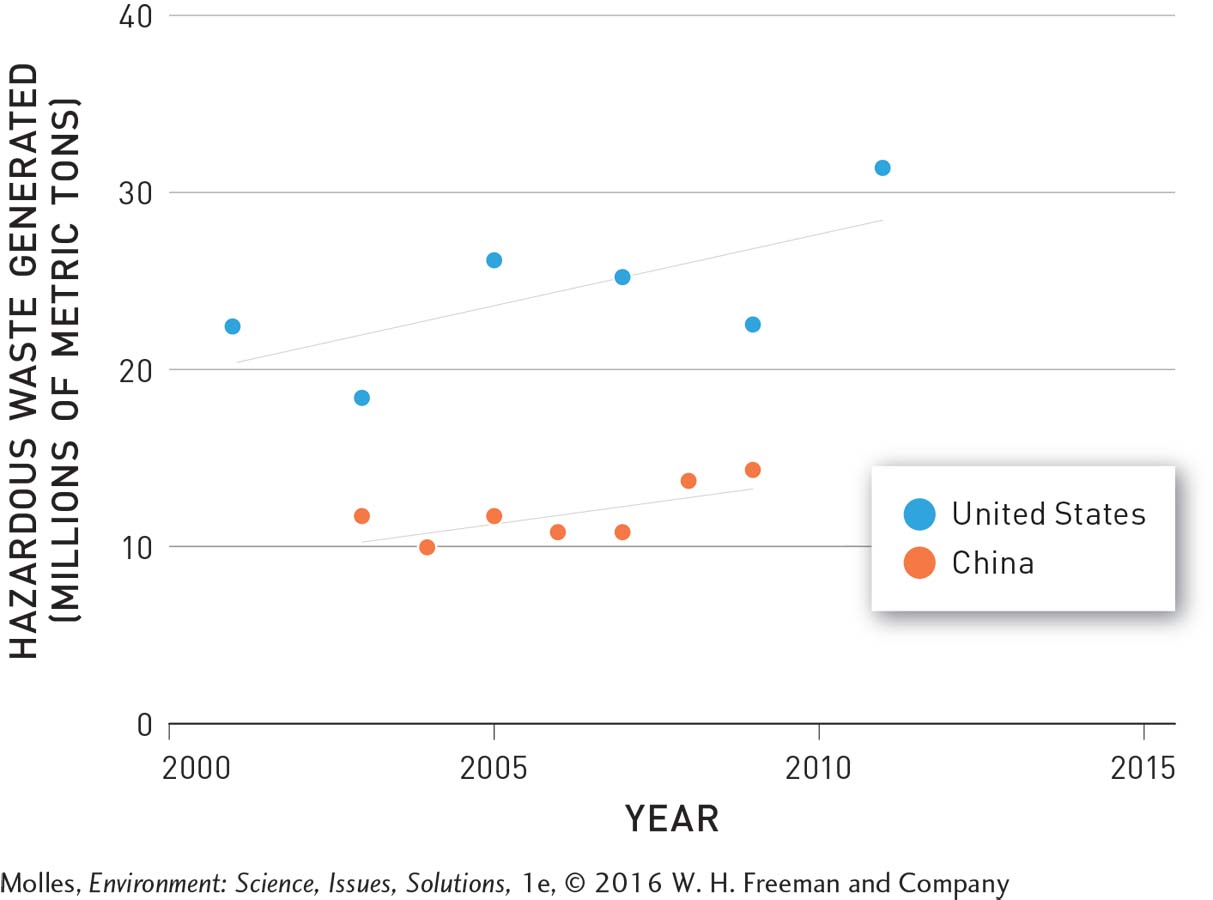

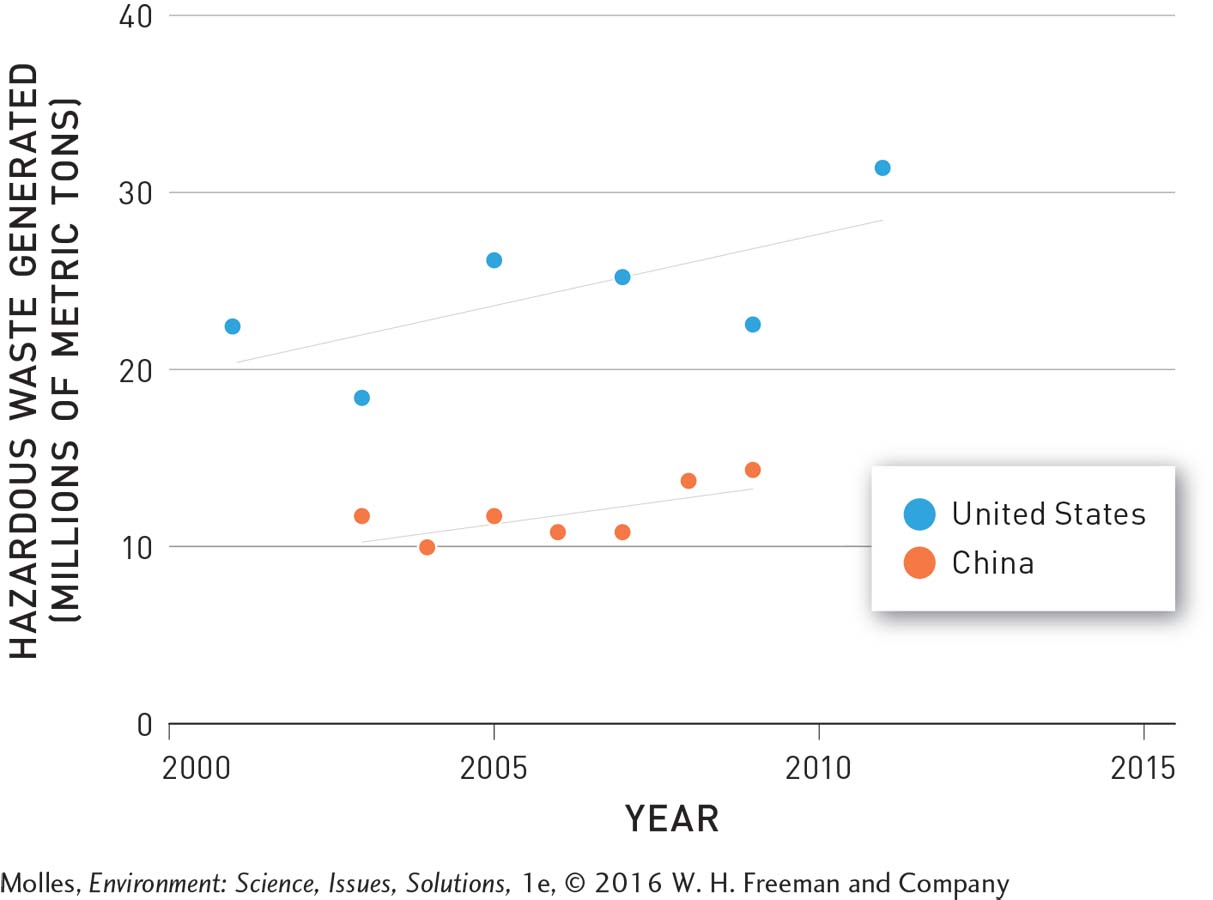

The generation of hazardous waste by the United States and China, the world’s two largest economies, increased by approximately 40% and 20%, respectively, within a decade or less (Figure 12.13). Figures are similar globally. The Basel Convention (discussed below) reported a 12% increase in hazardous waste being generated in 43 countries over a period of just 3 years, from 2004 to 2006.

YEARLY HAZARDOUS WASTE GENERATION BY THE WORLD’S TWO LARGEST ECONOMIES

FIGURE 12.13 The amount of hazardous waste generated by the United States and China increased during the first decade of the 20th century. (Data from EPA, 2011c; UNSD, 2011)

Electronic Waste

electronic waste (e-waste) A portion of the waste stream consisting of discarded electronic products that typically contain hazardous components (e.g., heavy metals like lead, and other toxins).

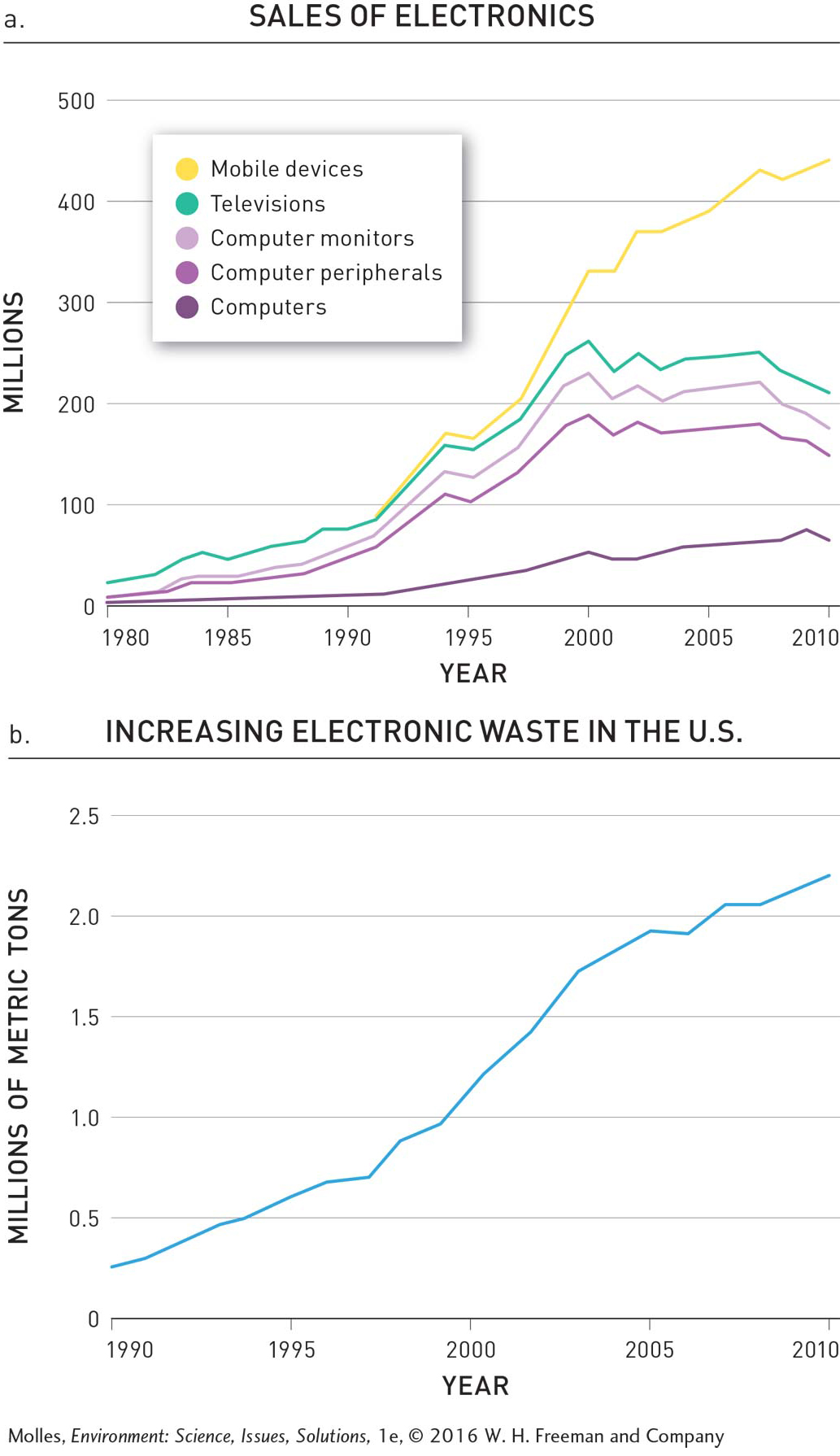

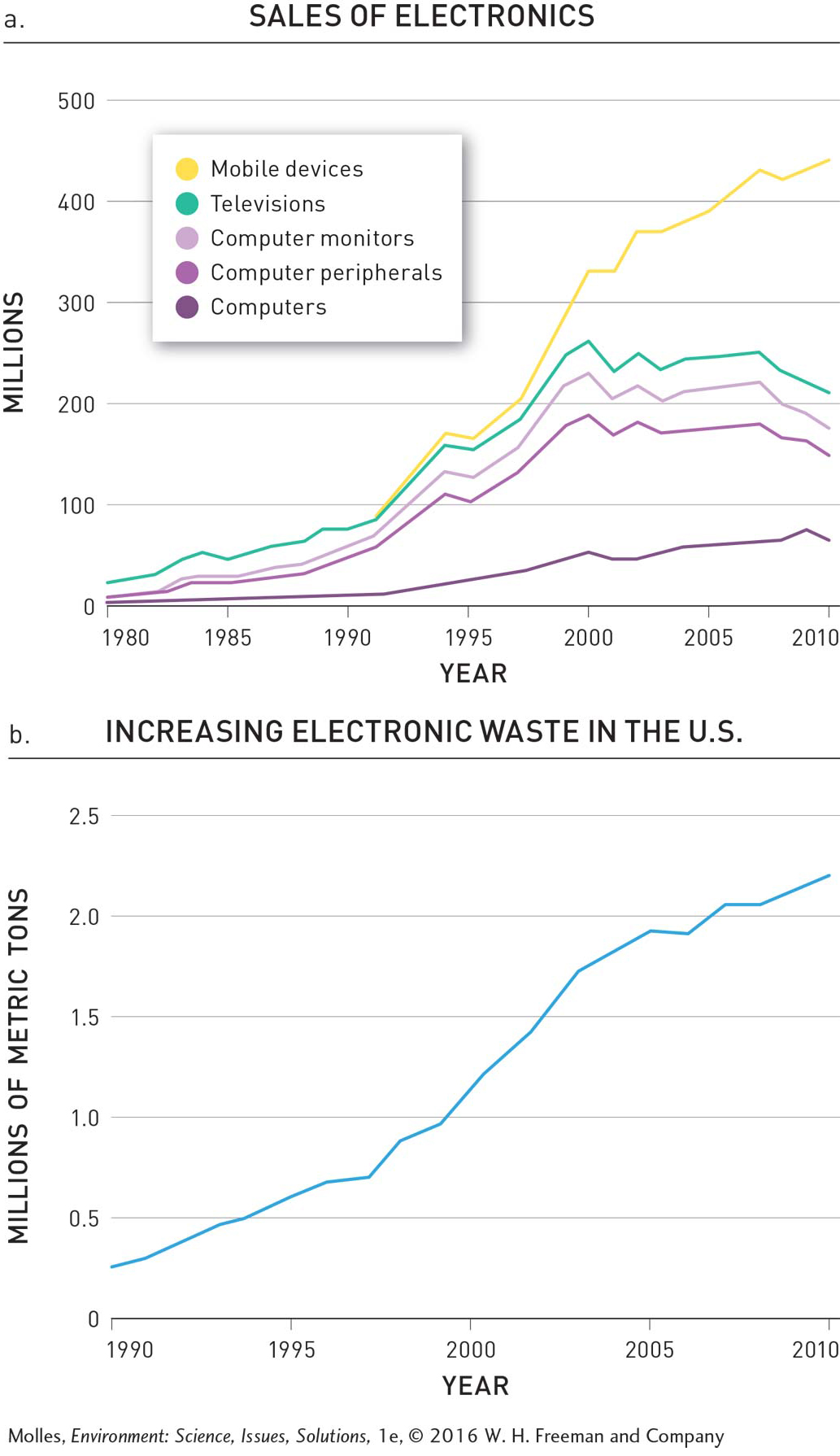

One type of waste that is posing new challenges is electronic waste, or e-waste, which often enters the municipal solid waste stream, even though it contains hazardous components. The use of electronic products has grown substantially over the past two decades, changing the way we communicate, as well as our various sources of information and entertainment. According to the Consumer Electronics Association, Americans now own approximately 24 electronic products per household. These levels of ownership are reflected in electronics sales in the United States, which skyrocketed between 1980 and 2010 (Figure 12.14a). Whether you are in the Silicon Valley of California or the so-called Silicon Savanna of Kenya, you are guaranteed to spot people tapping away on their cell phones.

AN ELECTRONICS REVOLUTION CREATES A NEW WASTE STREAM

FIGURE 12.14 (a) In just 30 years, from 1980 to 2010, U.S. sales of electronics increased from 22 million to 443 million devices and diversified from a market dominated by televisions to one made up of various electronics, ranging from computers to smart phones. (b) As electronic devices in the United States reach the end of their useful life, they enter the solid waste stream, creating a growing source of hazardous waste. (Data from EPA, 2011a)

At some point in the life cycle of these electronic devices, they wear out or are replaced by improved models. At that point, most unwanted televisions, personal computers, laptops, tablets, phones, and media players enter the waste stream as electronic waste. Electronic waste can be considered hazardous, as many of the inner components are toxic, corrosive, or reactive. Consider these common examples:

CRT (tube-style) monitors and televisions each contain significant amounts of lead.

LCD (flat-screen) monitors contain mercury.

Circuit boards found in nearly every electronic device contain multiple toxic substances, including cadmium, lead solder, and brominated flame-retardants.

The problem of electronic waste is growing, although it is largely hidden from most consumers. In 2010 over 2 million metric tons of e-waste were produced in the United States (Figure 12.14b). But these increases in e-waste are not limited to the United States—high levels of e-waste occur in all middle- to high-income countries, and those amounts are growing.

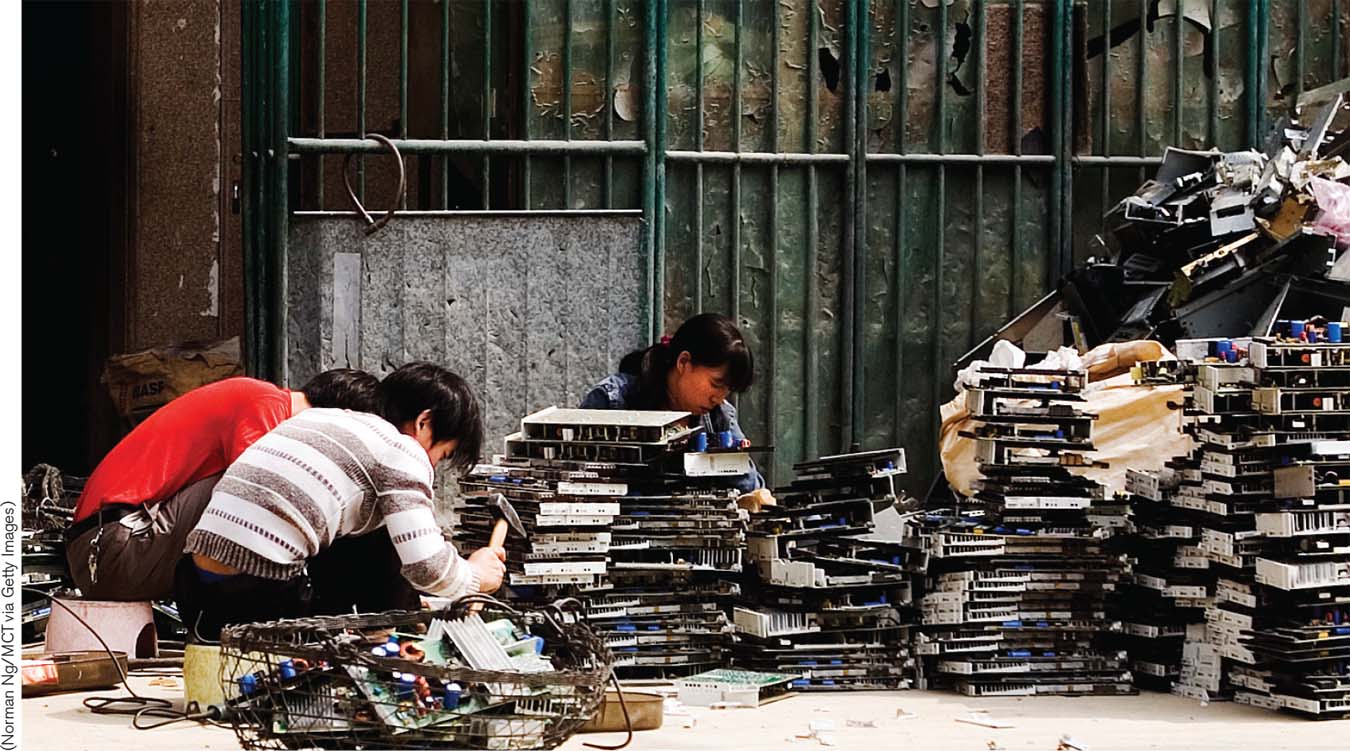

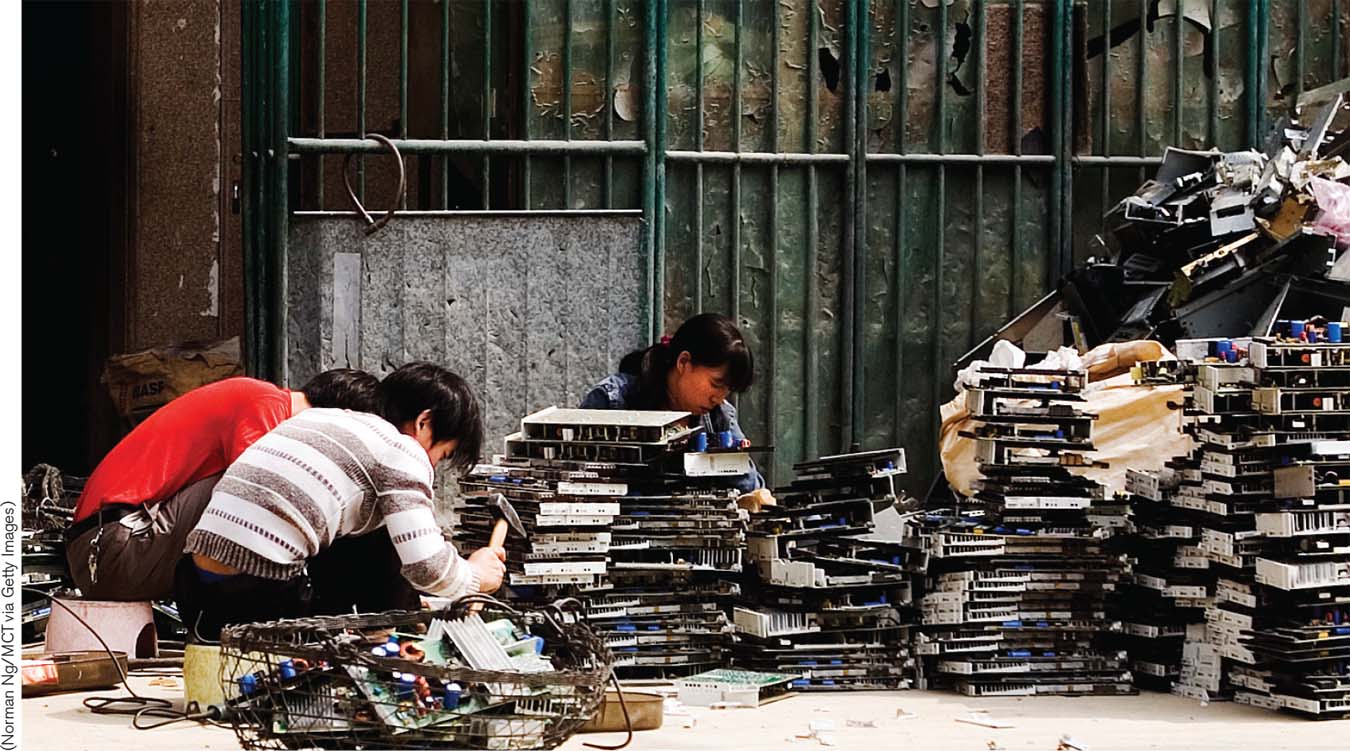

Unfortunately, e-waste is often illegally smuggled from developed countries to developing countries for disposal. It’s the story of the Khian Sea all over again. The cottage e-waste business involves labor-intensive and often hazardous manual dismantling of equipment, using simple tools like hammers and screwdrivers and salvaging and selling reusable component parts from circuit boards, compressors, appliances, and other electronic devices. The most lucrative practice is to separate out precious metals and then refine them. However, these cottage e-waste workers lack the technology, equipment, and training to safely manage the process.

Page 370

How is poverty connected to unsafe recycling of e-wastes?

Substandard informal recycling practices include open burning or melting of plastics, toner sweeping, dumping of lead-containing CRTs, acid stripping of printed wiring boards, and de-soldering of chips, as well as dumping waste chemicals onto the soil or into water sources. These common practices pose direct risks to the health of workers and to the local environment.

The global center for unsafe recycling practices has been Guiyu, China, a coastal city that imports electronic waste from all over the world (Figure 12.15). People from rural areas migrate to Guiyu, seeking jobs disassembling, burning, and melting the precious metals from circuit boards. With a population of 150,000, including 100,000 migrants, Guiyu is home to more than 300 companies and 3,000 individual workshops that are engaged in e-waste recycling. These e-waste workers, many of whom are women and children, earn an average wage equivalent to USD$1.50 per day.

INFORMAL E-WASTE PROCESSING IN GUIYU, CHINA

FIGURE 12.15 The methods for recovering valuable components from e-waste used by the informal sector in Guiyu, China, and elsewhere create conditions harmful to the health of workers and contaminate the environment with hazardous waste.

(Norman Ng/MCT via Getty Images)

According to the Basel Action Network, the majority (80%) of children in Guiyu have elevated levels of lead in their blood. Workers at these recycling sites face many health hazards. For instance, women working in these conditions run the risk of having children with birth defects, and the child workers are likely to suffer impaired neurological development. Although the Chinese government has banned these informal e-waste recycling practices, the environmental damage they cause will persist for many years and will require substantial effort and resources to mitigate.

Think About It

Many electronic items have a label of a trash bin with a line crossing through it. How might disposing of electronic waste with the rest of a household’s waste have far-reaching environmental consequences?

Why does the problem of e-waste receive a great deal of media attention, while the much larger amount of other hazardous wastes generated goes largely unreported?