13.2 Humans produce a wide variety of pollutants

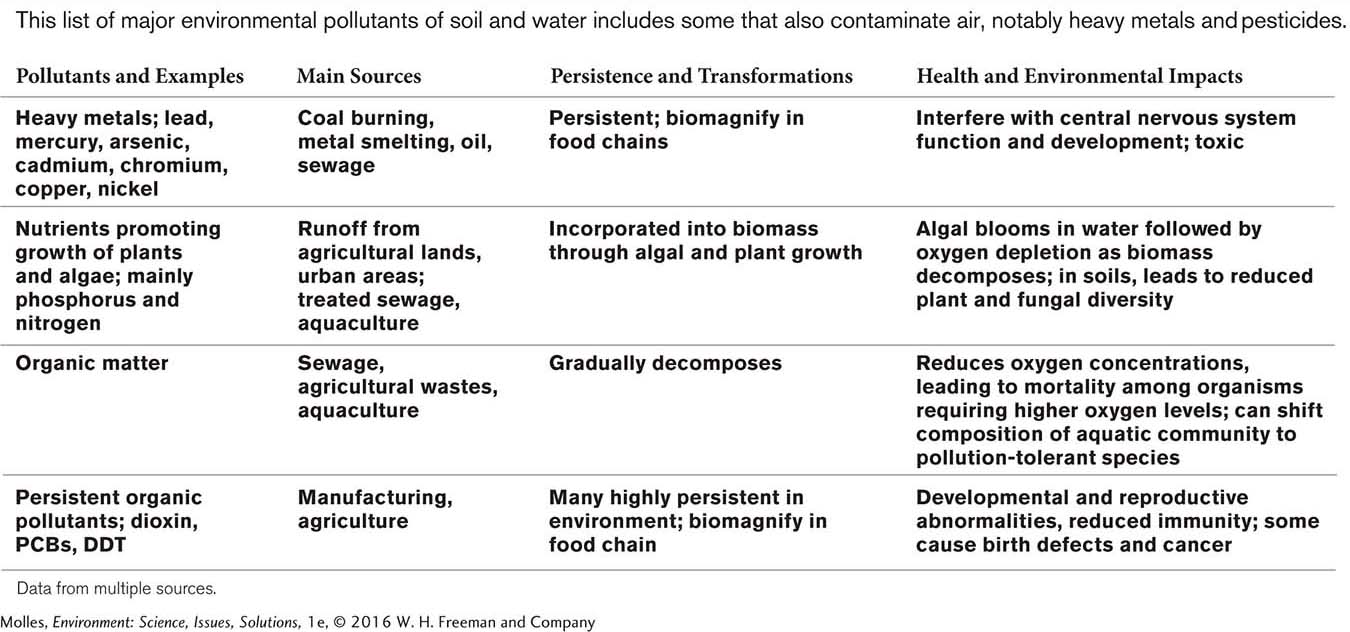

Pollution comes in many forms, some of which we’ve discussed already. In Chapter 7 and Chapter 8, we introduced issues associated with adding excessive organic matter, plant nutrients, and sediments to aquatic environments, and Chapter 9 covered oil spills and nuclear accidents. In addition, Chapter 11 examined pollutants of soil and water within the context of environmental health, including endocrine disruptors, heavy metals, pathogens, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals. Here, we expand those earlier discussions for some of the more problematic pollutants of water and soil (Table 13.1).

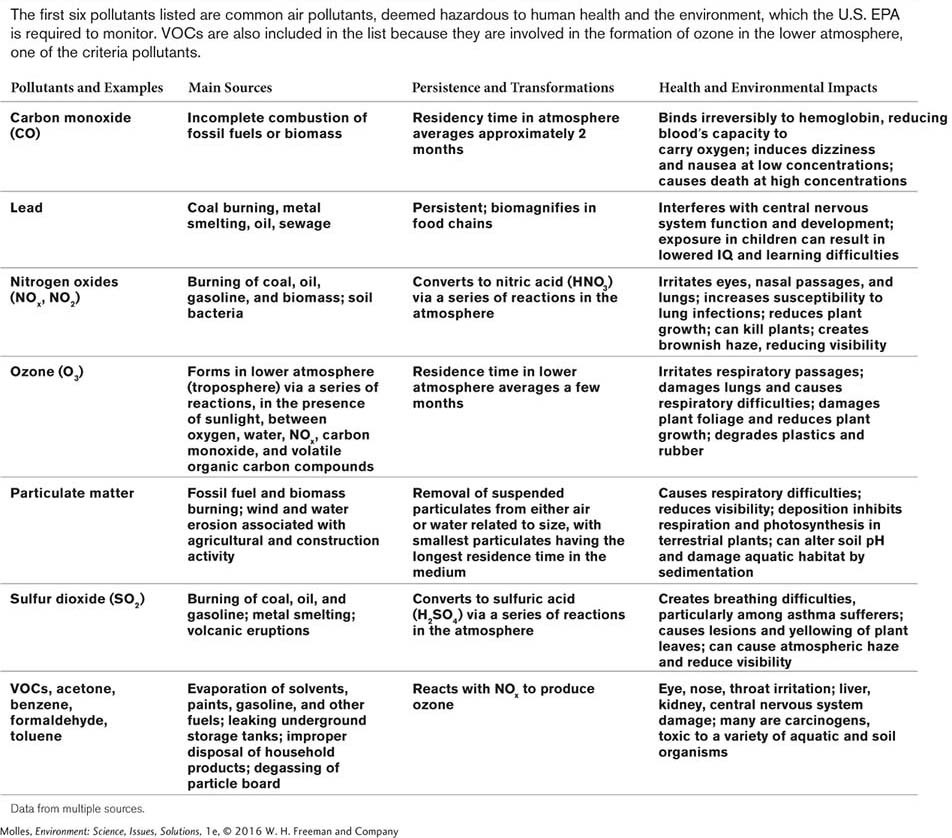

Criteria Air Pollutants

criteria pollutants Very common sources of air pollution (e.g., sulfur dioxide) chosen by the EPA to be regulated because they are hazardous to human health and the environment.

Although there are many substances that can contaminate air, some pollutants have been singled out for careful regulation. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established air-

Sulfur and Acid Rain

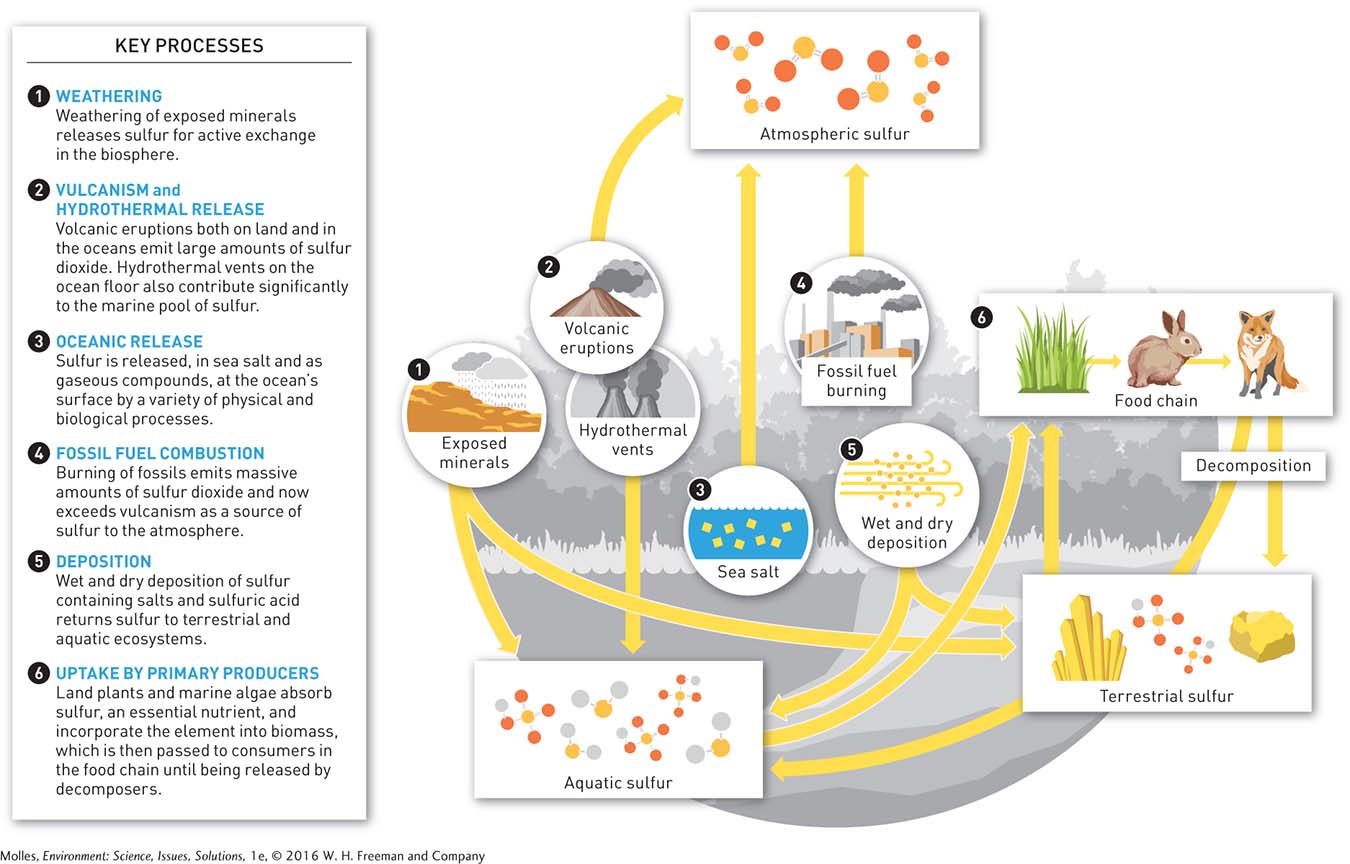

The element sulfur, as a component of proteins, many vitamins, and antioxidants, is essential to life. Like other elements, sulfur moves through the biosphere in a global biogeochemical cycle (Figure 13.4). Most sulfur on Earth is tied up in rocks and is released into the biosphere as these geologic materials are exposed by the rock cycle and weathered (see Appendix B). Seawater holds another major portion of Earth’s store of sulfur, which is actively exchanged with the atmosphere both as sea salt blown from the ocean’s surface and as a variety of gaseous, sulfur-

Should any measureable amount of sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere be considered a pollutant?

The ocean floor is also a site of significant release of sulfur into the biosphere at hydrothermal vents, where hot water rich in hydrogen sulfide (H2S) emerges and is quickly transformed to SO2 by sulfur-

How might the fact that the pH scale is logarithmic affect public perception of the significance associated with a pH shift of half a pH unit, for example, from 5.6 to 5.1?

acid rain Acidified rainfall. See acid deposition.

acid deposition An inclusive term that includes both wet and dry deposition of acids.

The chemist Robert Angus Smith appears to have been the first person to recognize and systematically study the phenomenon of acid rain. In 1852 he noticed that the acidity of rain increased as you moved from the countryside to cities throughout the British Isles, and understood that it had the potential to affect ecosystems. Acid rain forms when sulfur dioxide, SO2, undergoes chemical reactions in the atmosphere, forming sulfuric acid, H2SO4, a major source of acid rain, along with nitric acid, HNO3 (see Figure 13.3, page 390). Although we commonly use the term “acid rain” to refer to this phenomenon, it is more precise to call it acid deposition because it can occur as dry deposition, which happens when gases or tiny particles suspended in air are deposited directly onto a surface such as a plant leaf or lake surface, as well as in the form of snow and sleet. Even without pollution, rainfall is slightly acidic with a pH of around 5.6 (recall that a pH of 7.0 is neutral). Generally, rainfall with a pH of less than 5.3 is considered to be acid rain.

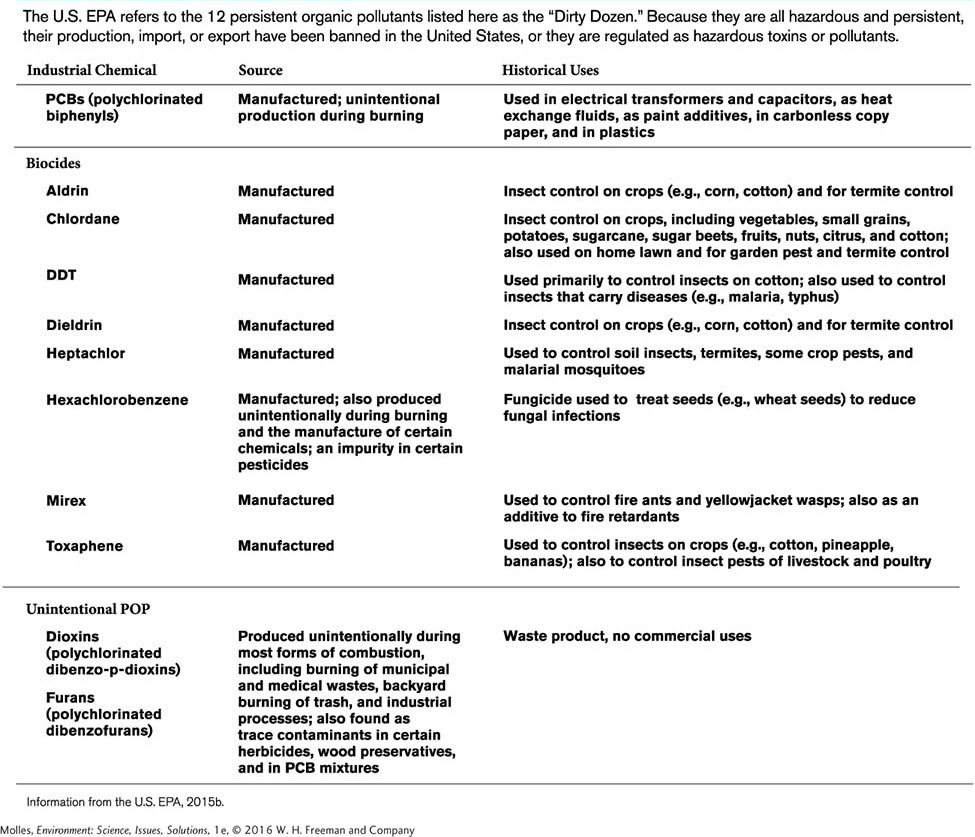

Persistent Organic Pollutants

persistent organic pollutants (POPs) Organic chemicals (e.g., PCBs) that remain in the environment indefinitely; can biomagnify through the food web and pose a threat to human health and the environment.

Persistent organic pollutants, or POPs, are chemicals that remain in the environment indefinitely, can biomagnify through the food web, and pose a threat to human health as well as to the environment. Because they break down only very slowly and generally under a narrow range of environmental circumstance, POPs can be transported over long distances, as air or water pollutants, across international and regional boundaries. These pollutants ultimately find their way to all corners of the planet, where they accumulate in the fatty tissues of consumers, including those of humans. Some of the POPs considered by the EPA to be particularly problematic are listed in Table 13.3.

Most of the chemicals listed in the table are manufactured and most are pesticides, although not all. For example, dioxins and furans are not manufactured but are produced unintentionally as a by-

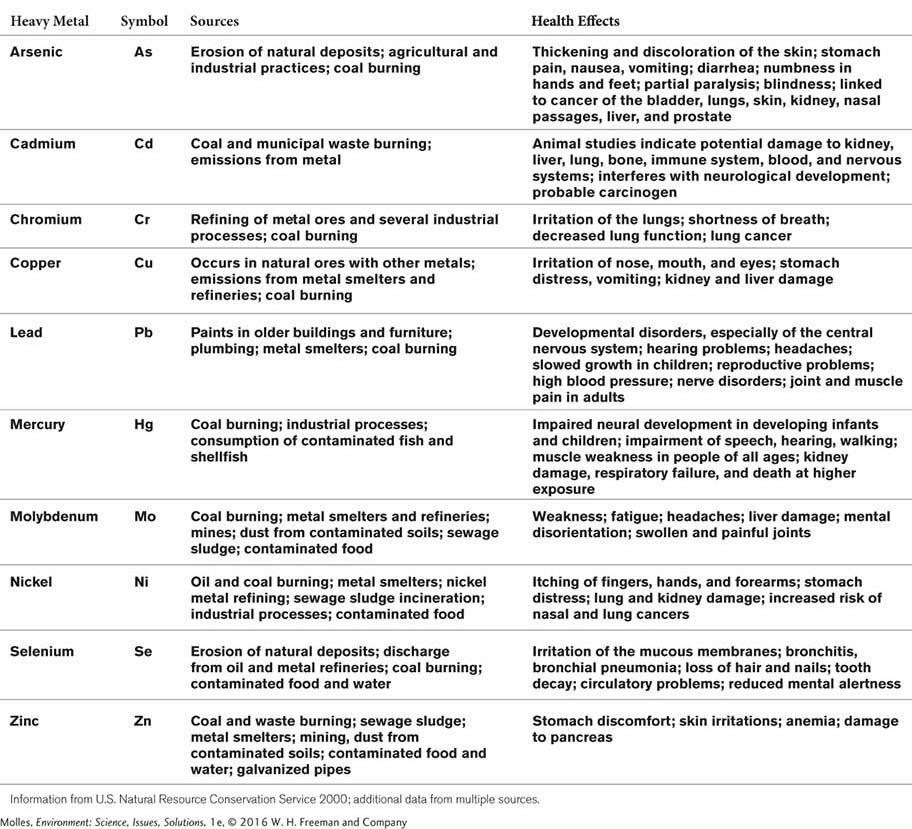

Heavy Metals

Heavy metals are metallic chemical elements with high atomic weights. Although there are many heavy metals, those of environmental concern are toxic to humans, animals, and plants (Table 13.4). Humans, plants, and animals require low doses of some heavy metals, such as copper and zinc, but at high concentrations the metals become toxic. Other metals, including mercury and lead, are toxic even at low concentrations. Arsenic and selenium are not technically metals but are generally included in lists of heavy metals because of their similar toxic effects and behavior in the environment. One of the most common sources of heavy metals is the burning of coal. Because coal represents the fossil remains of living organisms, it contains all of the elements in living systems in a concentrated form, including a wide array of heavy metals.

Organic Pollution

biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) An indicator of the amount of organic matter in water, measured as the quantity of oxygen consumed by microorganisms as they break down the organic matter in a sample of water.

Does all natural water have some BOD?

Excessive organic matter can stress aquatic ecosystems in particular. Organic pollution has several potential sources, including domestic sewage, aquaculture, and agriculture, especially concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs. All three are potential sources of massive inputs of organic matter into aquatic ecosystems—

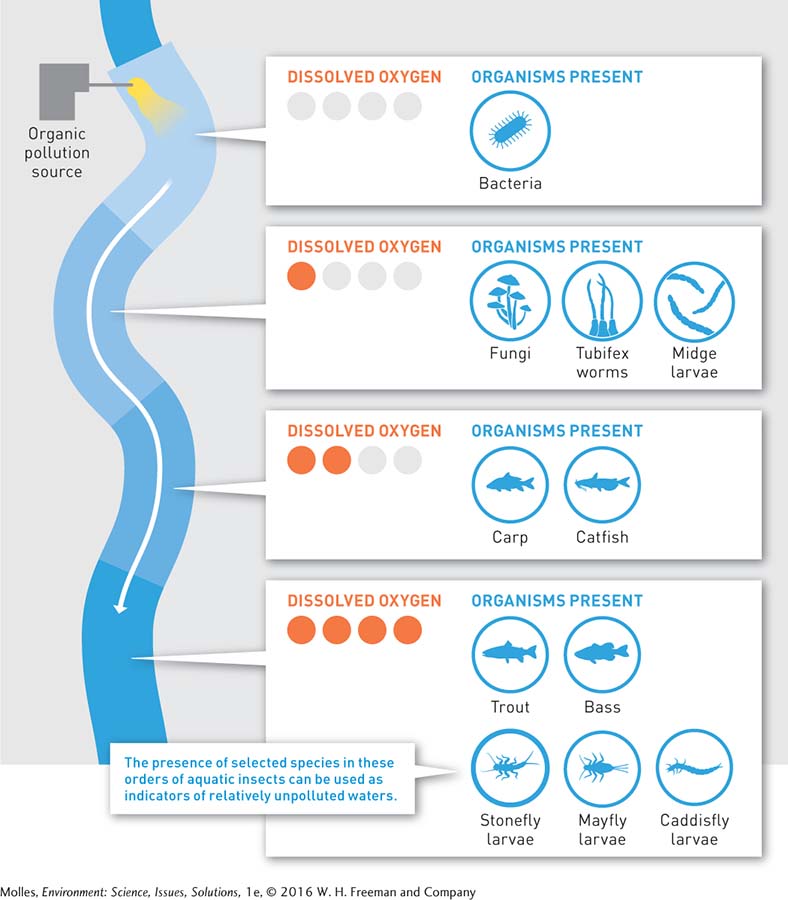

Where additions of organic matter are large and, consequently, BOD is high, respiration by the bacteria and fungi consuming the added organic matter can deplete dissolved oxygen to levels low enough that all organisms are eliminated except bacteria capable of living in the absence of oxygen (Figure 13.6). Downstream from this “anaerobic” zone, where some dissolved oxygen is present, you can commonly find dense growths of fungi feeding on the abundant organic matter, along with aquatic invertebrate animals, such as tubifex worms and midge larvae, which are tolerant of low oxygen conditions. Farther downstream, where oxygen levels are still low but somewhat higher, the fish community will be limited to species such as carp and catfish, which are tolerant of lower oxygen concentrations.

Cultural Eutrophication

eutrophication A natural process by which nutrients, especially those that limit primary production, build up in an ecosystem.

cultural eutrophication An accelerated process of eutrophication resulting from human activities (e.g., sewage disposal, agriculture) that increase the rate of nutrient addition to ecosystems; generally results in excessive algal or plant production, depletion of dissolved oxygen in aquatic ecosystems, and loss of biodiversity.

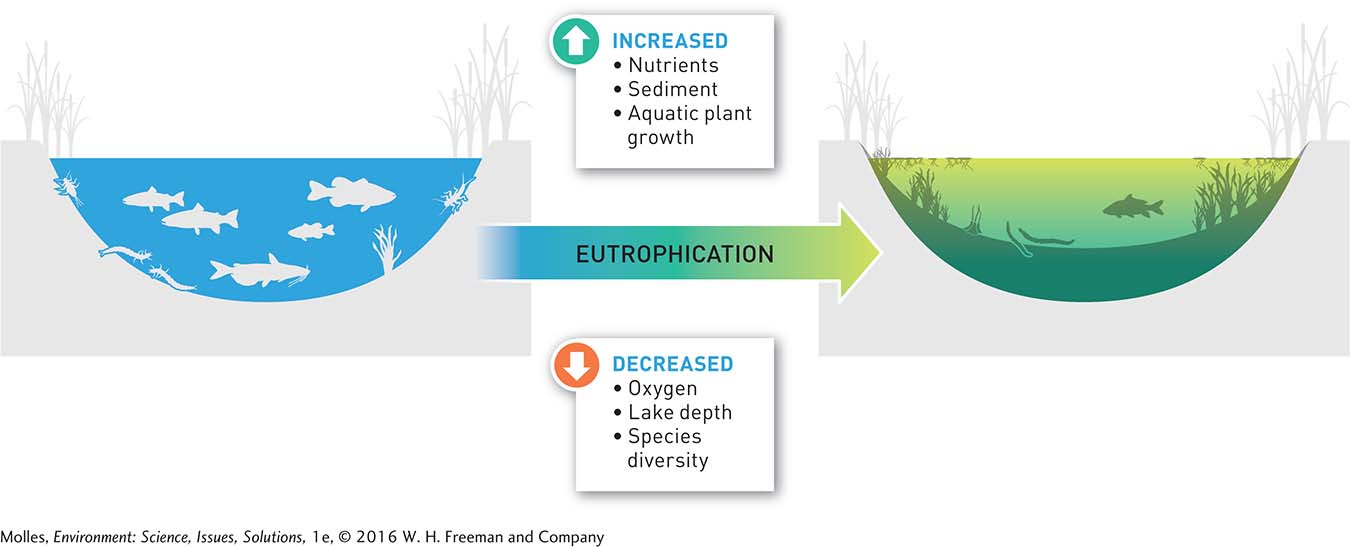

In natural ecosystems, nutrients gradually build up through a process called eutrophication. Most frequently studied in lakes, eutrophication includes increases in nutrient availability and sediments, decreases in lake depth, shifts in the makeup of the biological community, and increases in primary production (Figure 13.7). It can also occur on land and involve the accumulation of organic matter and inorganic nutrients in soils. Humans can accelerate eutrophication through the excessive addition of nutrients, such as sewage and fertilizer, either directly to a body of water or indirectly through runoff from the surrounding landscape. This condition is generally referred to as cultural eutrophication. Cultural eutrophication leads to excessive algae and plant growth, the depletion of dissolved oxygen in aquatic ecosystems, and the loss of biodiversity (Figure 13.8).

Think About It

What are the major differences between the sulfur cycle (see Figure 13.4) and the phosphorus cycle (see Figure 8.6, page 235)?

Of the vast number of potential pollutants, what properties would lead the U.S. EPA to choose just six as criteria pollutants?

Oxygen is important to the health of both aquatic and soil ecosystems. Why, then, is adding large amounts of organic matter considered a form of pollution in aquatic ecosystems, but not generally in soils?