13.8–13.12 Solutions

Sudbury stands as a lesson of what can occur when industry operates without checks and balances. Today, Sudbury is no longer the moonscape it once was. In recent decades, emissions of contaminants have dropped by 90%, soils have been improved, and more than 12 million trees have been planted. In the process, the people of Sudbury have built a much more diversified economy, which includes financial and business services, tourism, health care and research, education, and government. Sudbury has also become a regional center for the arts and culture. The reversal of fortunes by the people of Sudbury shows that it is possible to solve the immense problems posed by pollution.

Think about Earth’s air and water as one of the planet’s shared community resources. As we saw in Chapter 2, Garrett Hardin proposed that unregulated use of such resources would lead eventually to environmental damage, which he called a Tragedy of the Commons (see page 49). This is exactly what we have seen on the ground in Sudbury and in the air above Beijing. Preventing harm to these community resources requires, first and foremost, environmental regulations, which will ultimately spur new technologies and practices.

13.8 Environmental regulation and international treaties have played important roles in reducing pollution in North America

By the early 18th century, waterways in and around cities in North America became choked with pollution ranging from tannery chemicals to untreated sewage. It was not until 1948 that the Federal Water Pollution Control Act was passed to protect interstate waters, such as the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes, which supported fisheries and drinking water needs. Because there was no central environmental authority, the Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service was put in charge of developing programs to improve the quality of surface waters and groundwaters.

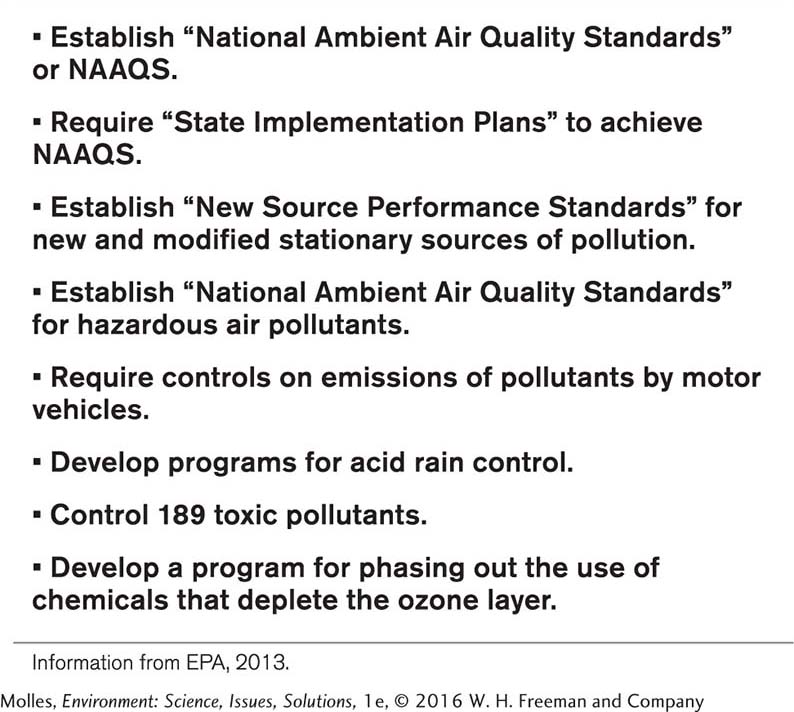

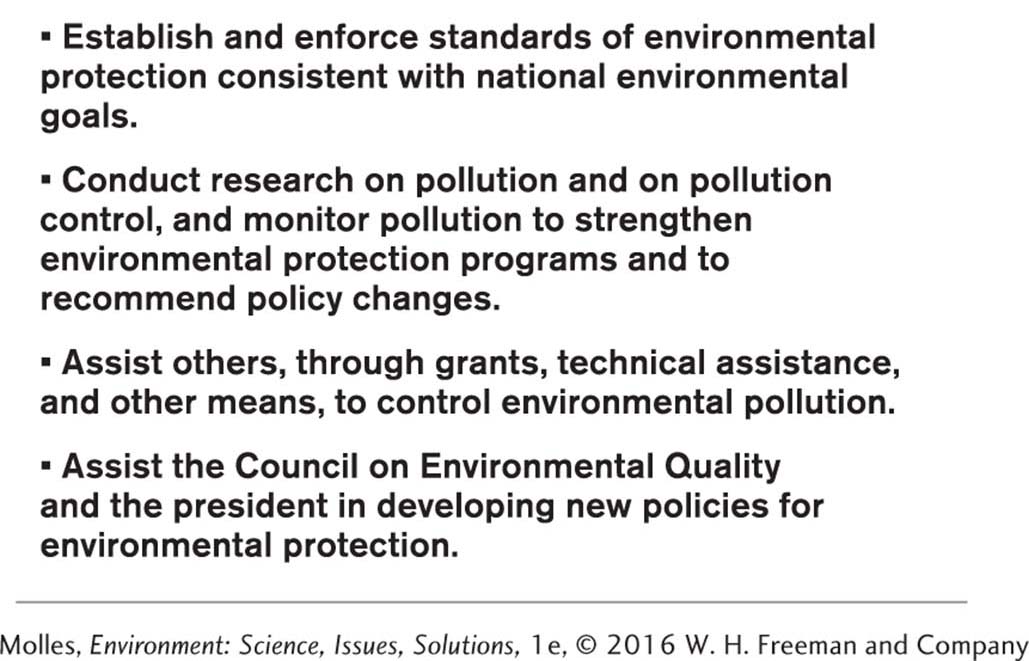

More than 20 years later, the United States created its first federal agency dedicated to the environment. Richard Nixon was running for president in 1968 and, recognizing growing popular concerns about pollution, made environmental issues part of his presidential campaign. After Nixon won the election, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act, generally known as NEPA; but Nixon went further, creating the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, through a 1970 executive order (Table 13.5). New federal laws to strengthen pollution controls soon followed.

The Clean Water Act

The long-

In 1972 the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, commonly known as the Clean Water Act (CWA), was thoroughly revised to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters” (EPA, 2012a). The act explicitly protects wetlands and estuaries from pollution and from dredging and filling.

In administering and enforcing the CWA, the EPA works closely with state and tribal governments to develop water quality standards, which play a pivotal role in judging how much of a pollutant may be discharged into a water body and which waters are polluted. States must survey their waters to determine which exceed the limits set by the standards and are categorized as “impaired.” States are also responsible for restoring impaired streams by reducing concentrations of pollutants.

What would be the likely consequences of environmental legislation without an overseeing agency such as the U.S. EPA?

The CWA has other important mechanisms for limiting pollution. For instance, if a paint manufacturer wants to discharge waste into U.S. waterways, it must apply for a permit. Permit applicants must demonstrate that the best available technology will be used to reduce the amount of pollutants discharged. The CWA also provides federal money for building or improving sewage treatment plants.

The CWA has continued to evolve. For example, the 1972 amendments to the CWA addressed only point sources of pollution, but its scope was expanded in 1987 to include nonpoint sources as well. In addition, the EPA has shifted from a case-

The Clean Air Act

The Air Pollution Control Act, the first U.S. federal law to address air quality, was passed in 1955. The role of the federal government in controlling air pollution expanded with the Clean Air Act of 1963, and the Air Quality Act of 1967 established air-

United States–Canadian Cooperation on Acid Rain

Recognizing their common need to address the issue of acid rain, Canada and the United States signed the U.S.–Canada Air Quality Agreement in 1991. The agreement is organized around three parts, called annexes. In Annex 1, the United States and Canada committed to limits on emissions and timetables for reducing emissions that cause acid rain. The two countries also agreed to notify and consult with each other regarding sources of acid deposition within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of the border.

Annex 2 focuses on scientific, technical, and economic activities and research to improve understanding of acid rain. Although the agreement was stimulated by the problems associated with acid rain common to the two countries, the agreement provided a flexible framework that could be used to address other cross-

Regulatory Mechanisms to Control Pollution

Most of the tools that the EPA uses to protect our air, water, and soil are command-

The EPA has also experimented with market-

The NOx reduction program also occurred in two phases. The EPA allowed flexibility on how electric utilities reduced their SO2 and NOx emissions. Companies could achieve these reductions through energy conservation, using more renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, installing pollution control technology, or switching to low-

Economic Benefits of Pollution Control

How might estimates of costs and benefits of environmental regulation be influenced by the financial interests of those making the estimates?

Regulations to control air pollution have been controversial due to the potential cost for industry. When controls on acid rain were proposed, for instance, the Edison Electric Institute, a lobbying group, predicted that the costs of controlling sulfur dioxide during just Phase I of the Acid Rain program would be $4 to $5 billion annually. Industry members projected that consumer utility bills would increase by 20% to 40%. In contrast, the EPA predicted annual costs would amount to $1 billion. In a review of the program, Don Munton, professor of international studies at the University of Northern British Columbia, found that these costs were overestimates, as he explained in the 1998 article “Dispelling the Myths of the Acid Rain Story.” The first years of the program cost only $836 million annually and utility bills actually increased an average of 2% to 4%. Munton concluded his review by stating that the Acid Rain Program was “a bargain.”

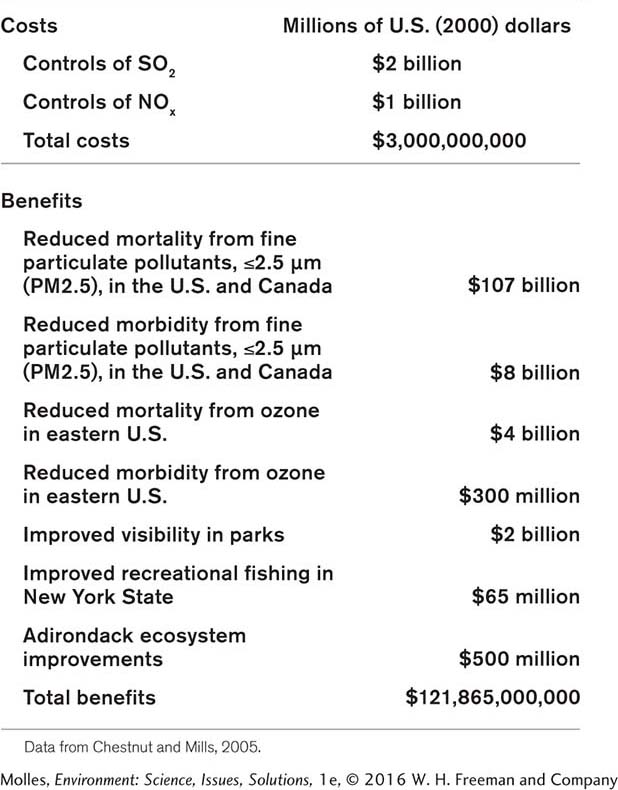

Other evidence is mounting that pollution controls can provide economic benefits that outweigh their costs. In a 2005 paper in the Journal of Environmental Management, Lauraine Chestnut and David Mills estimated that the total cost of Phase I and Phase II of the U.S. Acid Rain Program amounted to $3 billion annually (Table 13.7). The benefits included economic gains from reduced premature mortality and reduced chronic disease (morbidity) in the United States and Canada, as a result of controlling fine particulate pollution and ozone.

To these benefits, the authors added the economic gains resulting from improved visibility in U.S. parks, improved recreational fishing in New York, and ecosystem recovery in the Adirondacks. The sum of these annual economic benefits totaled nearly $122 billion, approximately 40 times the costs.

That’s the story for acid rain, but what about the total economic benefits of the Clean Air Act? In 2011 the EPA estimated that by 2020 the costs of pollution control would amount to $65 billion, but that those costs would be dwarfed by the economic benefits, primarily through a reduction of premature mortality, which would have totaled nearly $2 trillion. In economic and environmental terms, it appears that it pays to invest in pollution control.

Think About It

What aspects of the Clean Water Act imply recognition of the ecological services rendered by wetlands and estuaries?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of federal and state governments sharing in the process of setting pollution standards?

Could U.S.–Canada cooperation on pollution control be expanded into global-

scale cooperation to address pollution issues? Explain your position. How might conclusions reached regarding the economic viability of pollution control programs be influenced by whether one takes a long-

term (e.g., value to future generations) or short- term (e.g., quarterly profits to a company) perspective?