1.5–1.6 Issues

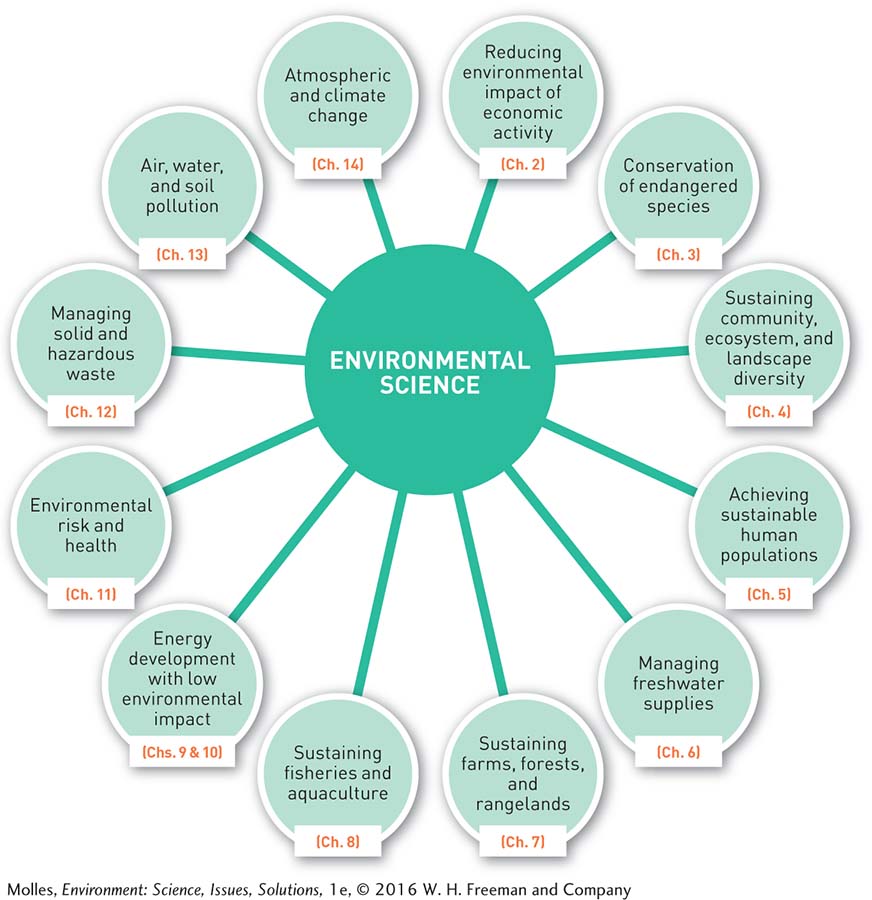

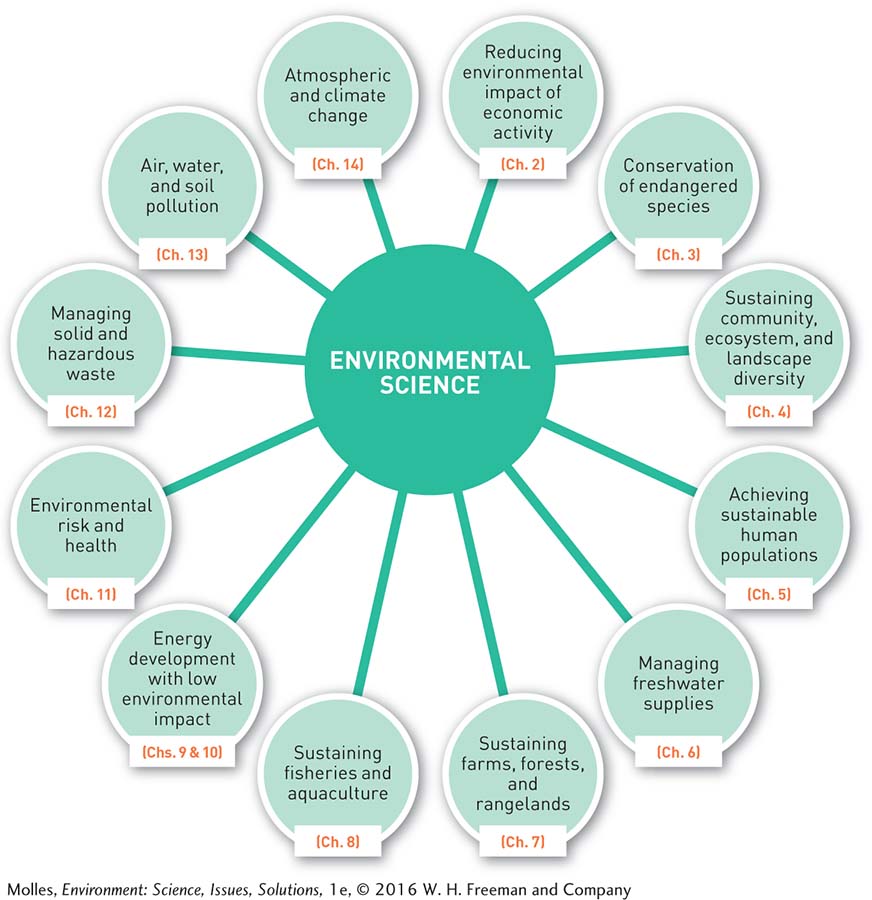

All species influence the environment in which they live, but human impact on the environment dwarfs that of other species. Earth is now home to 7 billion people. Farms have replaced natural vegetation, covering nearly 40% of Earth’s land surface. In the oceans, we have removed more than 90% of large fish over the last half-century. The burning of coal, oil, and natural gas spews 36 billion metric tons of climate-warming carbon dioxide per year. Some of the most pressing issues for environmental scientists are achieving a sustainable human population trajectory, maintaining the productivity of farmlands and aquatic ecosystems, protecting the biodiversity and natural ecosystems on which human welfare depends, and addressing rapid climate change (Figure 1.13) These impacts did not begin overnight, so it’s worth turning back the clock and exploring the history.

ENGAGING ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES AND EXPLORING SOLUTIONS USING ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE

FIGURE 1.13 The remainder of this book will examine major contemporary environmental issues and review potential ways to address them through the lens of environmental science.

1.5 Human impact and environmental awareness began long ago

When considering the environmental issues we face today, it is important to recognize that significant, society-changing environmental impacts by human populations began long ago (Figure 1.14).

ENVIRONMENT AND THE RISE AND FALL OF A CIVILIZATION

FIGURE 1.14 The Sumerian civilization was one of the first to build cities. The Sumerians depended on irrigated agriculture in the deserts of Mesopotamia, but salt buildup eventually rendered their soils unproductive. Today, the once thriving Sumerian cities are reduced to ruins surrounded by desert

(De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images)

Because people everywhere were once connected very closely with the environment around them, it is likely they recognized environmental changes as those events happened. However, we can only know for certain where observations of environmental change have been recorded in pictures or in words. Those records reveal that the first indications of environmental awareness, the forerunner to environmental science, began thousands of years ago.

Ancient Records of Environmental Impact

The first written records of environmental impact by human populations are over 2,000 years old. The early history of Greece includes numerous references to environmental impacts and recommendations on how to avoid damage to the environment. Wood was in great demand for building ships, for cooking and heating homes, and for the charcoal used in smelting metal ores and firing pottery. Consequently, the forests around Athens, one of the main cities of ancient Greece, were gone between 500 and 400 BCE. Both Plato and Aristotle—a natural scientist as well as a philosopher—recommended regulating the use of forests and grazing lands and establishing foresters and wardens to monitor forests and woodlands and to enforce environmental regulations.

In China, the philosopher Mencius, who lived in the 4th century BCE, was a skilled observer of the world around him. He also recorded examples of deforestation: “Bull Mountain was once beautifully wooded. But, because it was close to the city, its trees all fell to the axe.” Mencius recognized that the vegetation on Bull Mountain had the potential to recover, but it was prevented from doing so because of overgrazing by livestock: “However, as the days passed things grew and with the rains and the dews it was not without greenery. Then came the cattle and goats to graze. That is why, today, it has that scoured-like appearance.” Severe deforestation continued in China until modern times, with devastating impacts on the environment (Figure 1.15). Deforestation was also a problem in parts of pre-Columbian North America (Figure 1.16), medieval Britain, as well as North America during the Colonial period.

DEFORESTATION IN CHINA

FIGURE 1.15 Deforestation and resulting soil erosion were noted and recorded by Chinese scholars over 2,000 years ago. Today, China is attempting to reverse these losses through massive campaigns to restore once forested lands.

(Jim Richardson/National Geographic Creative)

CHACO NATIONAL MONUMENT, NEW MEXICO

FIGURE 1.16 When the Anasazi (a civilization that lived in the American Southwest from 200 CE to 1300 CE) constructed Pueblo Bonito, the building site was surrounded by productive woodland. Woodcutting and drought gradually converted the woodland into a desert shrubland, exhausting the Anasazi’s sources of wood for fuel and building.

(Radoslaw Lecyk/Shutterstock)

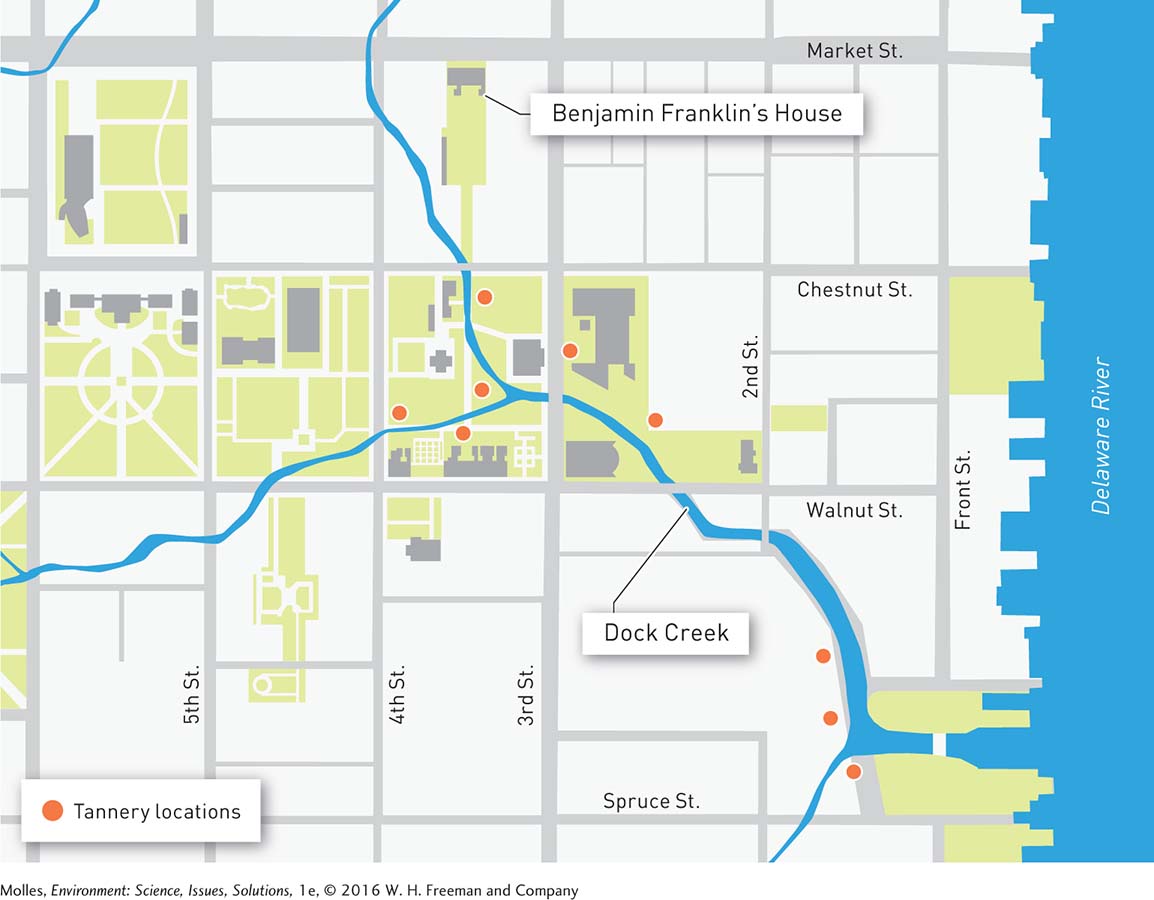

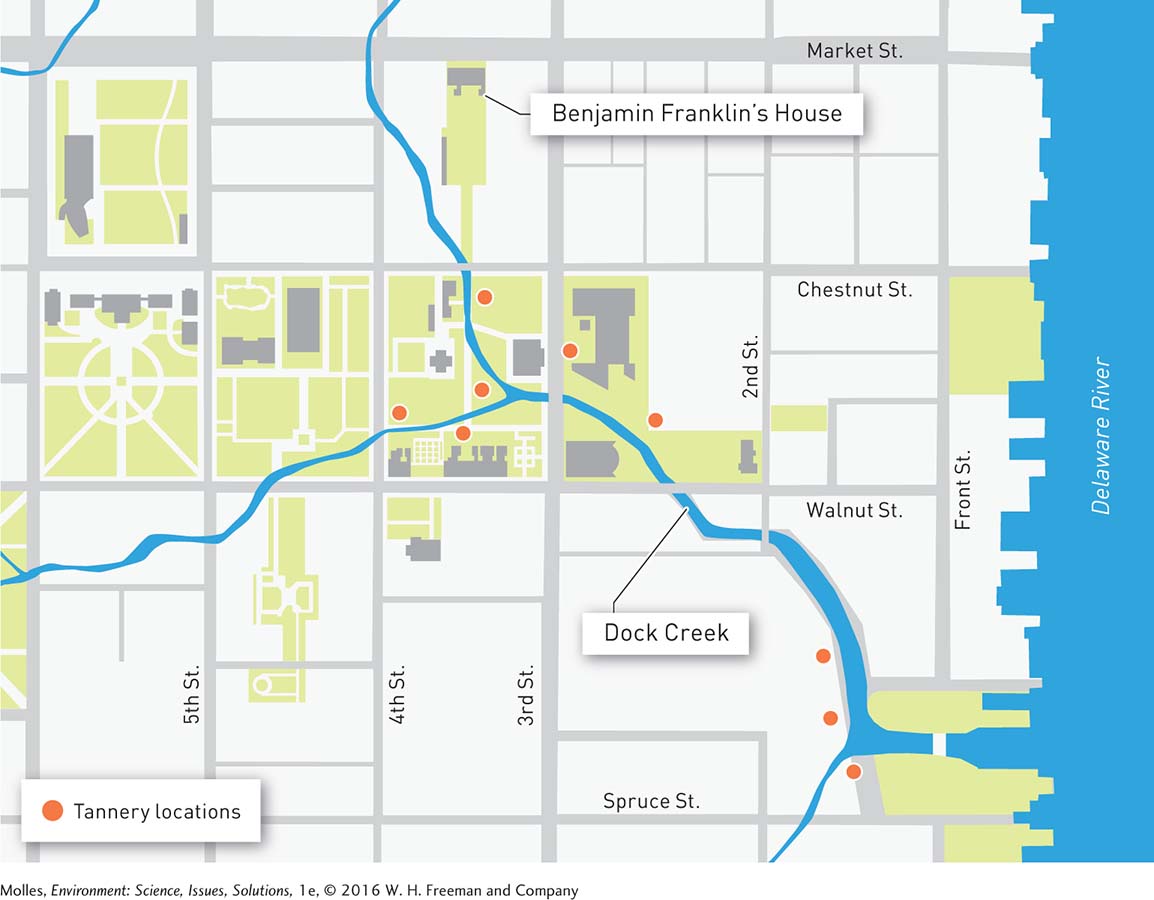

Benjamin Franklin and Environmental Protection

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) may be best known for his political and scientific accomplishments in the 18th century, such as helping craft the United States’ Declaration of Independence or studying the electrical nature of lightning. However, Franklin was also an early American environmental activist, leading the struggle, for instance, to reduce industrial pollution in his adopted home, the city of Philadelphia. In 1739 Franklin and his neighbors petitioned the local government to move leather-tanning operations, or tanneries, to locations away from the city center, where they were discharging wastes into Dock Creek (Figure 1.17). In addition to reducing the value of properties in the area, the presence of the tanneries made moving through the city center slow, thereby making fire-fighting difficult. During the conflict, Franklin used the paper he ran, the Pennsylvania Gazette, to argue that by creating a public nuisance, the activities of a few businesses were harming the daily lives and economic well-being of large numbers of Philadelphians. In the end, however, the power and influence of the tanners prevailed and Dock Creek would continue to be used as an open sewer until it was covered over in the early 19th century.

IN 1739 PHILADELPHIA USED DOCK CREEK FOR WASTE DISPOSAL

FIGURE 1.17 Leather-tanning yards were built along Dock Creek, where they disposed of their wastes, creating a stench that permeated the surrounding neighborhoods—including the one where Benjamin Franklin lived.

What are some ways in which economic and environmental interests might have found common ground in Colonial Philadelphia?

Page 16

Franklin also wrote extensively about the influence of environmental conditions on disease, especially yellow fever, which killed 500 residents and visitors to Philadelphia just two years after the tannery petition. Always thinking about the welfare of his fellow Philadelphians, Franklin included in his will plans for the building of a water system that would deliver clean water to the city, as well as the money to pay for that system. In one essay, Franklin also outlined his ideas about the main controls on human population growth.

Thomas Malthus, Population Growth, and Resources

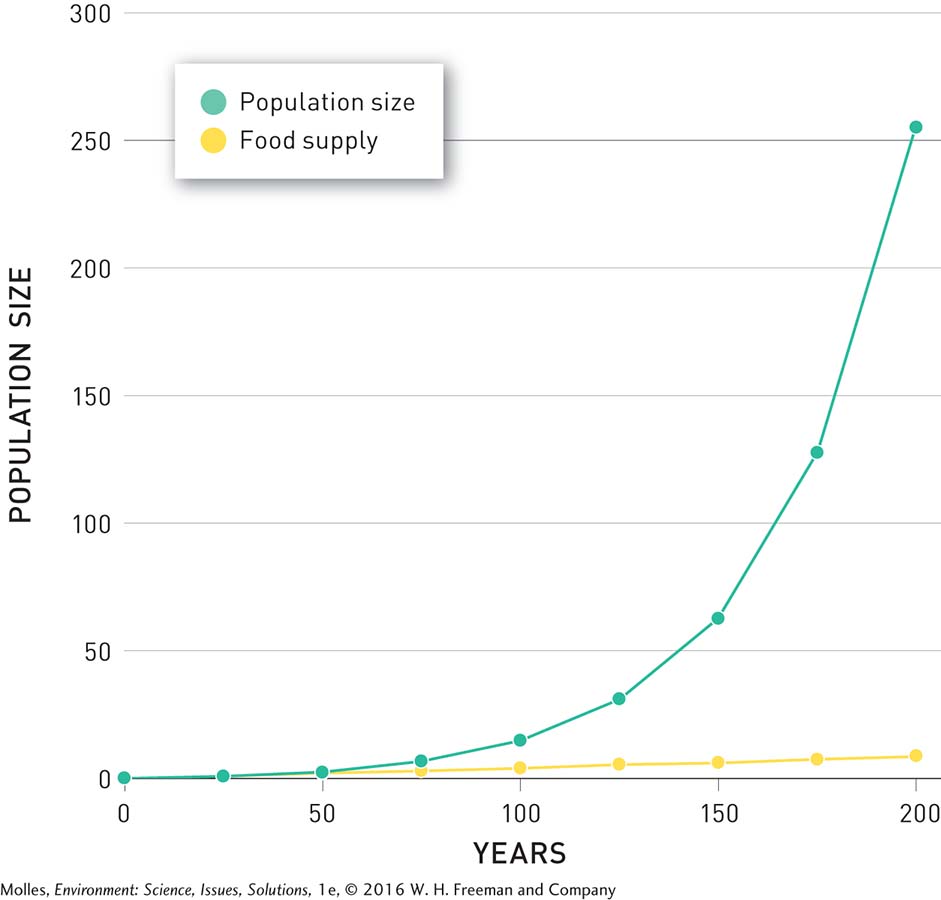

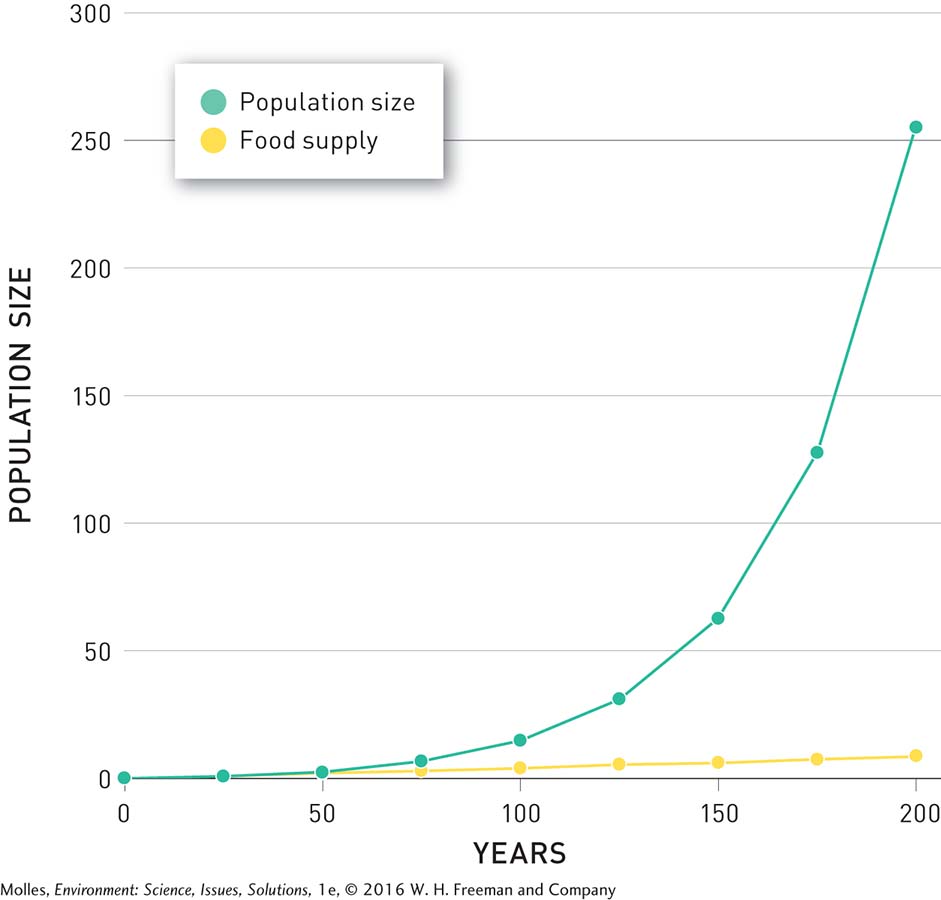

Born in England, Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), a member of the Anglican clergy, pursued a number of academic interests, including the work for which he is best known: the principles governing human population growth. Malthus was skeptical of the writings of a number of authors of his time, who predicted a future utopian world of healthy thriving human populations free from historical wants and afflictions, such as hunger, disease, and war. He had observed that there were no perfect human societies in his time, nor did historical records suggest that one had ever existed. Malthus proposed that human populations had the capacity to grow faster than society could increase its capacity to serve them, especially when it came to food supply (Figure 1.18). He predicted that a human population would grow past the capacity of the environment to support it even if all potential lands were converted to producing food for the population.

COMPARISON OF GROWTH IN A HUMAN POPULATION WITH GROWTH IN FOOD SUPPLY

FIGURE 1.18 Malthus used mathematics to show that a human population doubling every 25 years would soon outpace growth in the food supply, even if the food supply was increased every year by the total production capacity in year 1.

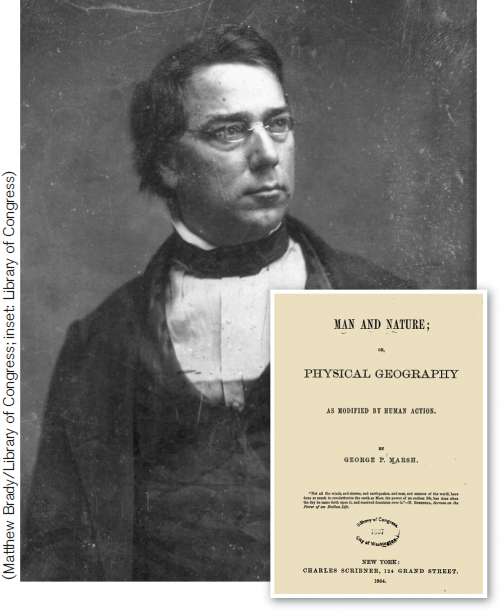

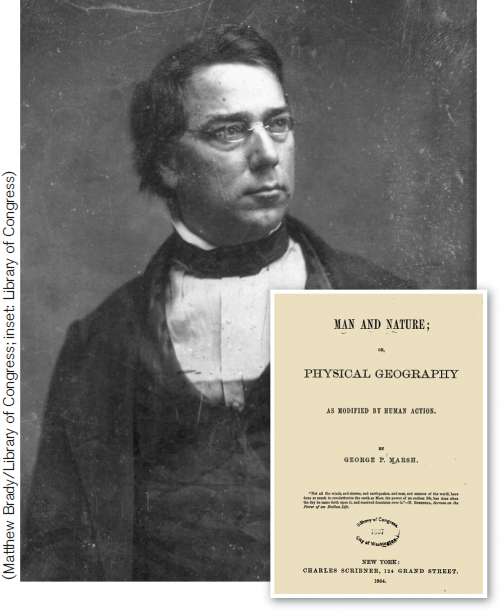

George Perkins Marsh: Human Populations and Nature

George Perkins Marsh (1801–1882) is mainly remembered for Man and Nature, the first environmental science book written by an American, which he published in 1864 (Figure 1.19). However, this was just one facet of Marsh’s varied life work. Born in Vermont in 1801, Marsh practiced law but he also worked as a sheep farmer, businessman, lecturer, U.S. congressman, linguist (he spoke 20 languages), and diplomat. Marsh traveled extensively in the Middle East through places that were stark deserts, though they were described in the Bible as lush and productive.

GEORGE PERKINS MARSH, FIRST AMERICAN AUTHOR OF AN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE BOOK

FIGURE 1.19 Marsh’s 1864 book, which included topics such as deforestation, extinction of animals, desertification, destruction of wetlands, and climate change, now seems eerily prophetic.

(Matthew Brady/Library of Congress; inset: Library of Congress)

Page 17

These experiences, combined with the changes he had observed during his early life in Vermont, convinced him that environmental impact by humans could change productive land into desert wastes. Marsh’s writings about nature and its uses and abuses were widely read and came at a critical time, when massive industrialization was occurring around the world.

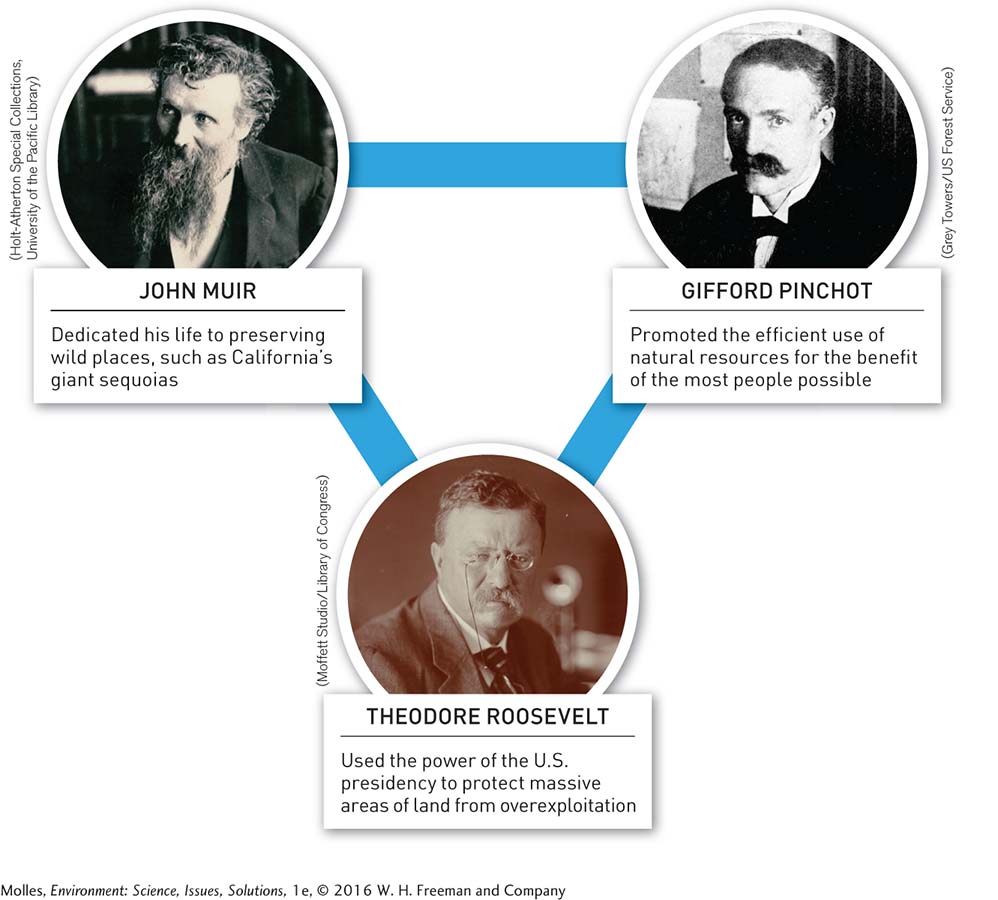

Land Conservation and Preservation in the United States

preservation ethic An environmental ethic emphasizing the protection of natural ecosystems in their original unspoiled states.

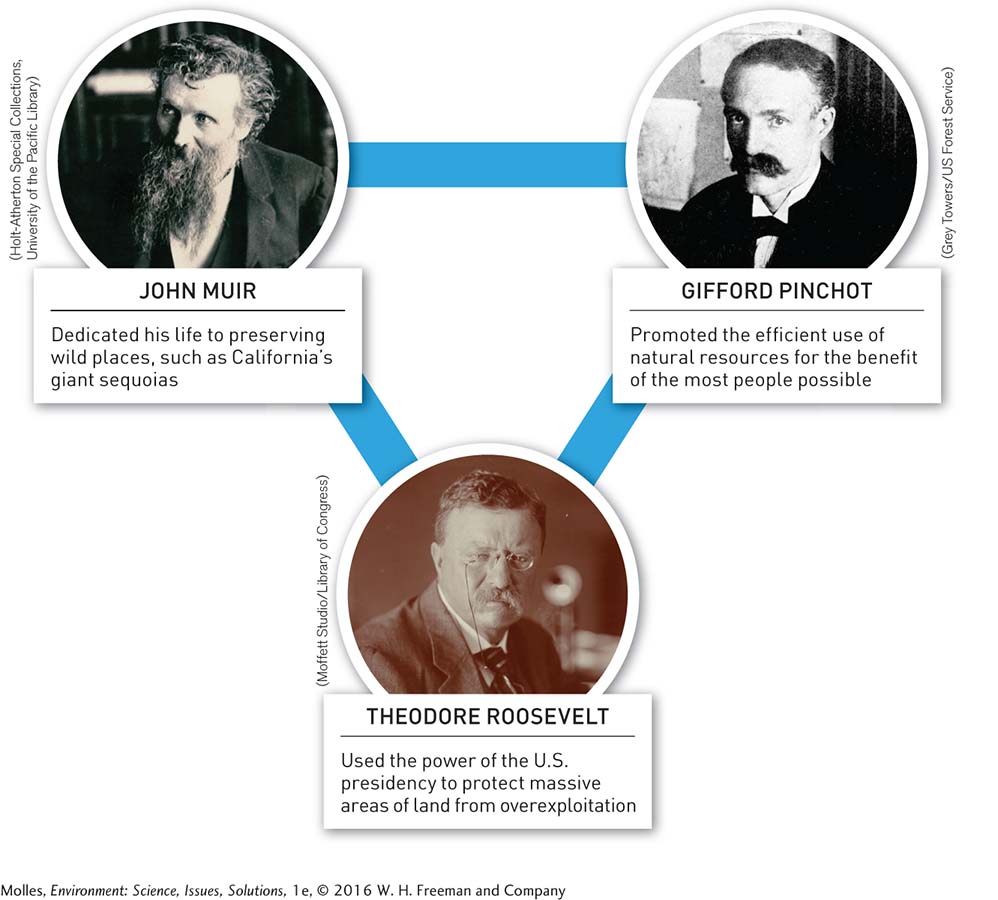

Marsh’s writings inspired three early leaders of land protection in the United States (Figure 1.20). One of those leaders was John Muir (1838–1914), a Scottish-born American naturalist. Muir’s family immigrated to Wisconsin, where he eventually attended the University of Wisconsin, an experience that deepened his appreciation for nature, particularly for botany and geology. In 1868 Muir moved west to California, where he began promoting the preservation of Yosemite Valley and other lands. Muir was an early advocate of a preservation ethic, an environmental ethic emphasizing the protection of natural ecosystems in their original unspoiled states. His evocative, poetic writings and his long-term advocacy for land preservation made him a central figure in the environmental movement, which was advanced by Muir’s founding of the Sierra Club.

UNITED BY HISTORY: JOHN MUIR, GIFFORD PINCHOT, AND THEODORE ROOSEVELT

FIGURE 1.20 With the writings of George Perkins Marsh serving as their inspiration, John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and Theodore Roosevelt worked tirelessly throughout their lives to protect the natural heritage of the United States.

(Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library); (Grey Towers/US Forest Service); (Moffett Studio/Library of Congress)

conservation ethic A philosophy of resource management that promotes the efficient use of natural resources to provide the greatest good to the greatest number of people.

The second of the three figures linked to Marsh’s book was Gifford Pinchot (1865–1946), first chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Pinchot was born to a wealthy family that had made its fortune through lumbering. His father, regretting some of the damage that lumbering was doing to the land, endowed the Yale School of Forestry and encouraged his son to pursue a career in forestry management. Pinchot’s ideas centered on his conservation ethic, which promoted the efficient use of natural resources, a philosophy that put him on a collision course for conflict with John Muir. In Pinchot’s words, “When conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run.”

conservation The preservation, wise use, or restoration of species, ecosystems, or natural resources.

Page 18

This philosophy guides the management of the U.S. Forest Service to this day. During the course of his professional life, Pinchot worked with several U.S. presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919). Roosevelt, a legendary outdoorsman who was president from 1901 to 1909, was deeply moved by Marsh’s book. In a speech on October 4, 1907, he asserted, “The conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem, it will avail us little to solve all others.” Conservation includes the preservation, wise use, or restoration of species, ecosystems, or natural resources. He created 150 national forests, 5 national parks, and 18 national monuments, along with numerous other protected areas. In total, Roosevelt protected over 930,000 square kilometers (360,000 square miles), an area equal to the combined territories of California, Oregon, Washington, and Ohio. While the environmental harm that Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Muir campaigned to avoid on the landscape is visually obvious, other, less visible human threats to the environment were still on the horizon.

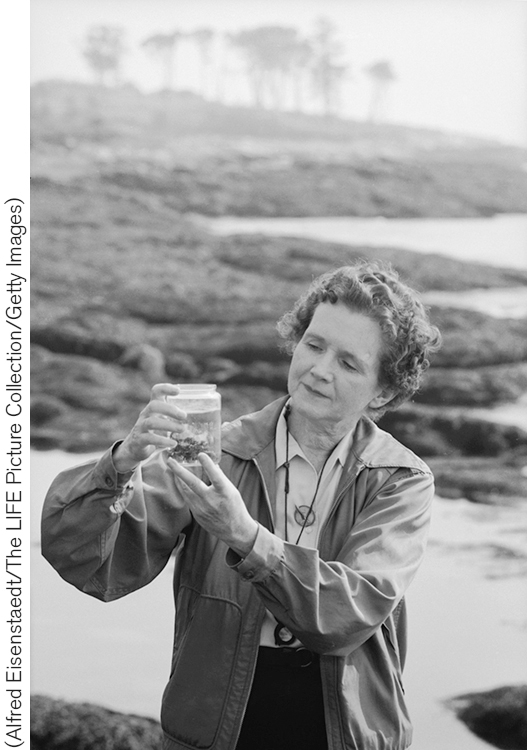

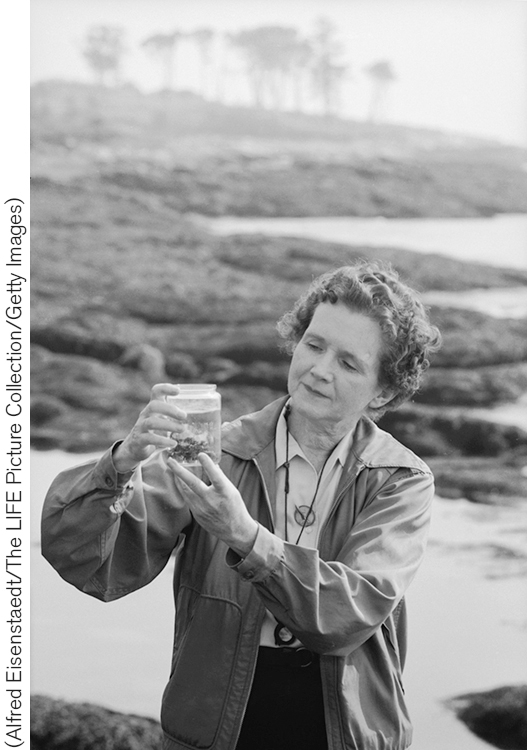

Rachel Carson’s Warnings

Born in the Allegheny Valley, Rachel Carson (1907–1964) was a child of the countryside. Carson entered the Pennsylvania College for Women as an English major, changing her major to zoology in her junior year. After obtaining a master’s degree at Johns Hopkins, she found work as a writer and editor for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, where she began writing magazine articles and books (Figure 1.21). In 1962 she published what would become her best-known book, Silent Spring, which warned of the potential dangers of indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides, a practice that became common following World War II. DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) was first widely used during the war as an insecticide to control malaria, and several other insecticides were created during the late 1940s and 1950s. Hailed as the ultimate weapon in the fight against insect pests, the application of these chemical poisons was killing far more than the targeted insects, including birds and fish.

RACHEL CARSON, SCIENTIST, AUTHOR, AND ADVOCATE FOR PRECAUTION IN THE USE OF CHEMICAL PESTICIDES

FIGURE 1.21 Rachel Carson likely did more to alert people to the potential dangers of chemical pesticides than anyone in history.

(Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

As a result, Carson and many others became concerned about their potential to harm the environment. They were also alarmed that heavy spraying of chemical insecticides threatened humans, since some of them, including DDT, had been classified as chemical carcinogens. In her book, Carson urged caution in our application of chemical insecticides. She warned that we might inadvertently destroy the birds that for millions of years had greeted the day with a “dawn chorus,” producing, in our attempts to control insects, a “silent spring.”

The chemical industry that made the pesticides, and the agricultural entities that made use of the pesticides, quickly went on a campaign to vilify Carson and other concerned environmentalists. They led organized attacks on Silent Spring, attempting to discredit both the book and its author. Carson was portrayed as a “hysterical woman,” a “liar,” and a promoter of “junk science.”

Her opponents also asserted that she was not qualified to write the book. Carson’s position, however, was vindicated in 1963 by President John F. Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee, which agreed that pesticides had been abused and represented a threat to the environment. Carson didn’t live to see the passing of the Clean Water Act in 1972 or the banning of DDT in the United States that same year. But, as a consequence of the DDT ban, the peregrine falcon recovered from the brink of extinction and the bald eagle, the symbol of the nation, is common once again across the lower 48 states and off the endangered species list (Figure 1.22).

THE BALD EAGLE: SYMBOL OF A NATION AND IMPRESSIVE BENEFICIARY OF THE DDT BAN

FIGURE 1.22 Before the ban on DDT use, accumulation of DDT in the prey of bald eagles had reduced reproduction by the eagles, driving them to near extinction in the contiguous United States.

(Dennis W. Donohue/Shutterstock)

Think About It

What do early human impacts on forests, which began more than 2,000 years ago, suggest about the historic relation of economic activity and environmental impact?

At the scale of the entire globe, the huge mismatch between food production and the human population that Malthus predicted has not yet occurred. What does this suggest about the assumptions made by Malthus? Since his dire predictions failed to materialize, can we safely ignore the ideas he developed?

Page 19

How might the destruction of the great bison herds of North America and the near extirpation of many other wildlife species, all of which occurred within the lifetimes of John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and Theodore Roosevelt, have affected the development of the conservation movement in the United States?

How might the precautionary principle have influenced Rachel Carson’s recommendations for pesticide use?