2.8–2.10 Solutions

Economic development does not have to lead to environmental degradation. Certainly, some limited resources will inevitably be depleted over time, but history shows us that improvements in resource use efficiency coupled with smarter regulations can reduce the impact of growing economies. Consider the story of sulfur-

As nations’ economies grew in the 1960s, they put more vehicles on the road and built more factories, which led to greater amounts of sulfur-

2.8 Economics should include environmental costs and benefits

Every time you drive to work or school in your car, you add to the traffic on the road and cause a little damage to the pavement. As thousands of others in your hometown do the same every day of the year, the damage accumulates and the road will inevitably need to be repaired and, perhaps, widened. In the previous section, we brought up the concept of economic externalities, which are the costs or benefits to society or the environment not included in the price of a product or activity. In this case, road damage is an externality associated with driving motor vehicles on roads maintained at public expense. Government regulations exist to prevent such market failures and take several forms.

Command-and-Control Regulations

command-

The most obvious solution to preventing harm to society is through command-

In Chapter 1, we introduced the discovery that CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) were causing an ozone hole over the Antarctic. Companies that produced CFCs were profiting as they harmed the environment—

The success of such command-

Pigovian Taxes

Command-

What activities would you reduce, if you were taxed for them based on their environmental impacts?

In 1920 an economist named Arthur C. Pigou became the first to propose taxing economic externalities, such as the damage caused by driving. His ideas caught on, and today we pay for roads in the United States through vehicle registration fees and taxes on fuel, which generally correlate with the number of miles a person drives. Since 2003 the city of London has charged a 10-

environmental economics A branch of economics that draws mainly from the field of economics as it assesses and manages the costs and benefits of economic impacts on the environment.

These taxes also contribute to the field of study called environmental economics, which includes the environment in its models. In its analyses, environmental economics draws mainly from the field of economics in its assessments and management of costs and benefits of economic impacts on the environment. For example, the way that environmental economists control damage to the environment by economic externalities, such as pollution, is to put a tax on the externality proportional to its damage to the environment. For instance, Pigovian taxes have been proposed for the emission of carbon dioxide and other pollutants in the atmosphere, where an outright ban is impractical. Pigou also thought that economic activities that benefit the environment should be encouraged through government subsidies. As with command-

Ecological Economics

natural capital The value of the world’s natural assets (e.g., minerals, air, water, and living organisms).

ecological economics A branch of economics that draws on many disciplines in studies of the influence of economic activity on the environment in an attempt to build a conceptual bridge between humans and human institutions and the rest of nature.

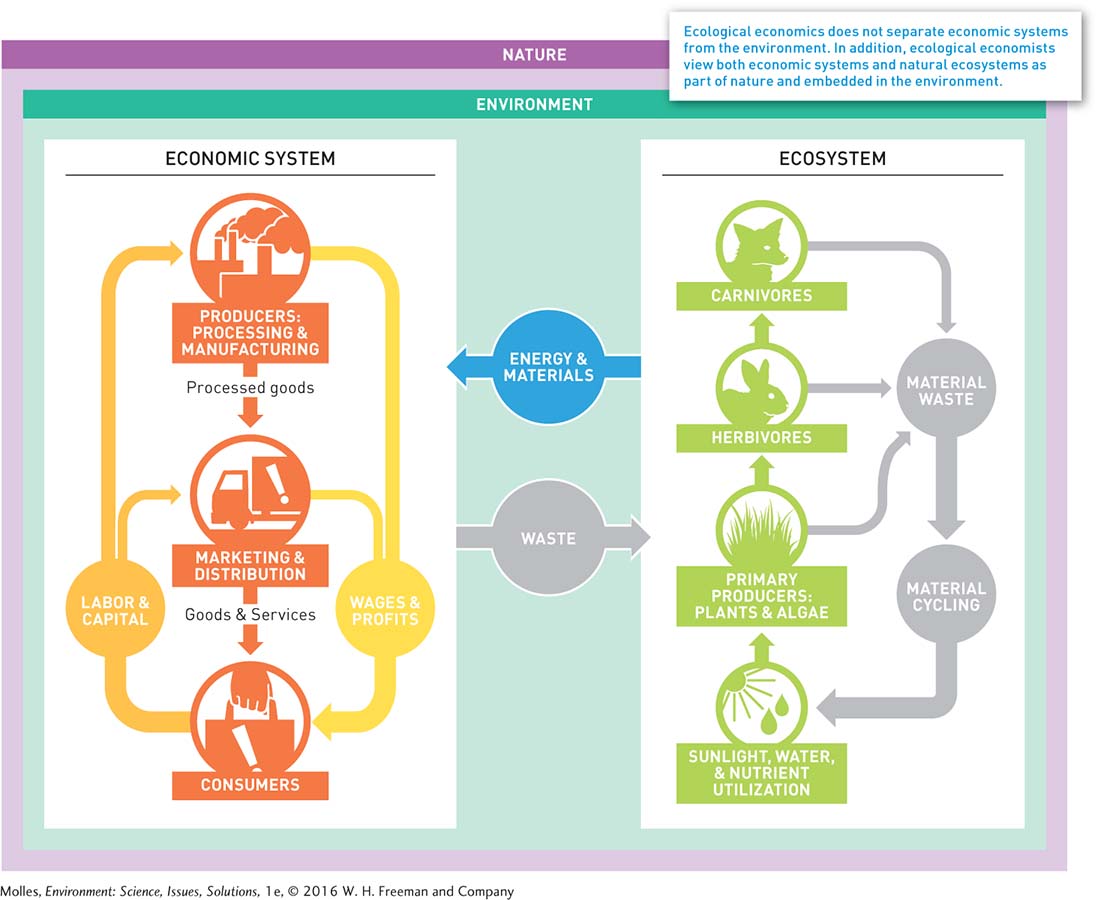

For economists, money is the fundamental metric of value. But even when they have tried to incorporate externalities into their economic models, some ecologists believe that they still undervalue natural capital, which is all of Earth’s natural assets, including plants and animals, minerals and soils, and air and water. In contrast to environmental economics, the field of ecological economics draws from many disciplines, including economics, in its studies of the relationships between economic activity and its impact on natural capital. Whereas conventional economics has seen people and their institutions as nearly alone in the world, and traditional ecology has focused most of its studies on ecosystems occupied by species other than humans, ecological economics attempts to build a conceptual bridge between humans and human institutions and the rest of nature (Figure 2.22).

ecosystem services The benefits that humans receive from natural ecosystems such as food, water purification, pollination of crops, carbon storage, and medicines.

Rather than seeking only to maximize financial capital through short-

Think About It

Why are the analyses of ecological economists necessarily more complex than those of environmental economists?

What aspect of CFC depletion of the ozone layer made that issue better addressed by a command-

and- control approach than did using Pigovian taxes? What are possible reasons why some have resisted putting a monetary value on nature’s ecosystem services?