3.12 Population ecology provides a conceptual foundation for wolf restoration

Population ecology provides a general framework for guiding restoration of endangered species and for predicting how their populations will respond during restoration. Gray wolf restoration provides a clear example of the utility of population ecology for managing endangered species.

Promoting Genetic Diversity

Genetic analysis gives environmental scientists essential tools for restoring endangered species populations. For instance, restoration of wolf populations in Yellowstone, Idaho, and along the Arizona–

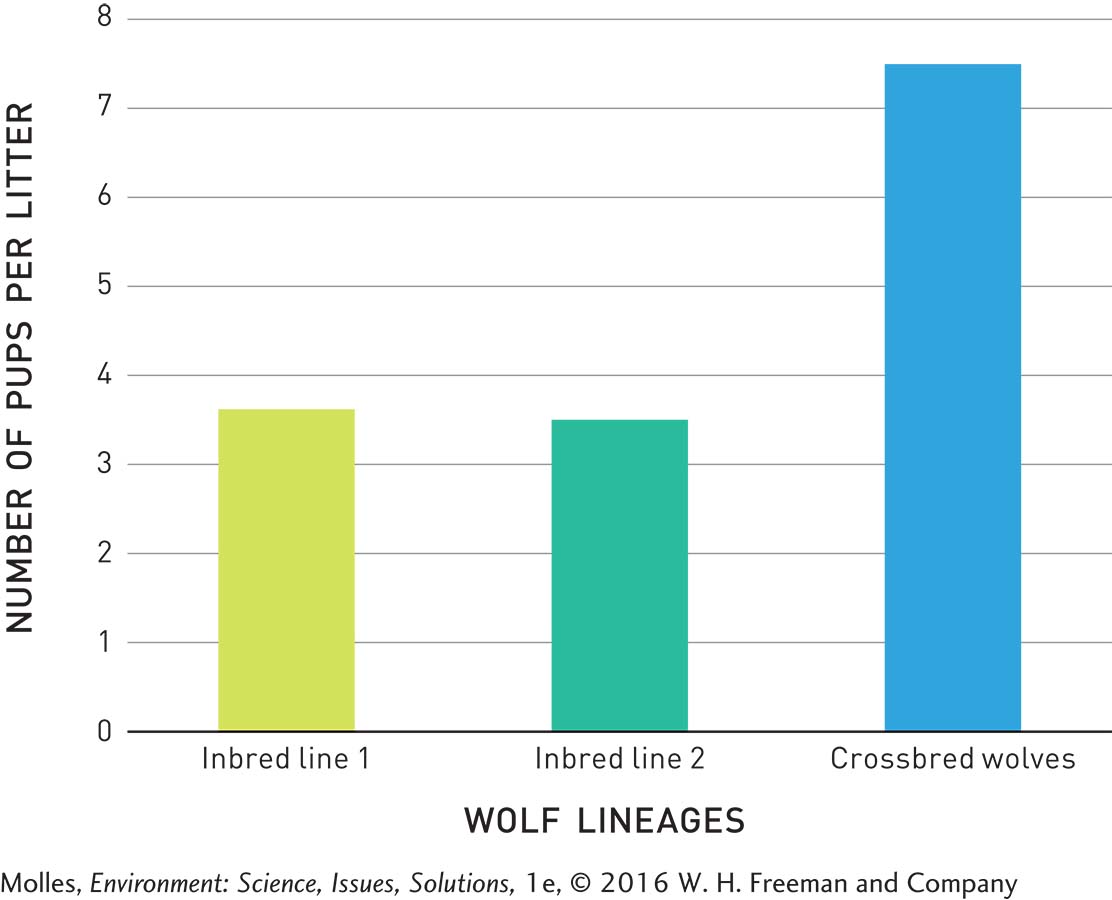

Compared with the wolves of the Northern Rocky Mountains, there is much less genetic variation among the small population of surviving Mexican gray wolves (see Figure 3.24, page 80), which are the descendants of three unrelated but highly inbred lineages. However, biologists discovered sufficient remaining diversity in these three surviving lineages to improve the chances of success by the population. By crossbreeding descendants of the three lineages, they have been able to more than double litter sizes from an average of 3.5 or 3.6 pups to 7.5 pups per litter (Figure 3.29). In addition, crossbred Mexican wolf pups also have an 18% to 21% higher chance of surviving to 6 months of age. Such positive effects of increasing genetic diversity are called genetic rescue.

Logistic Population Growth in a K-selected Species

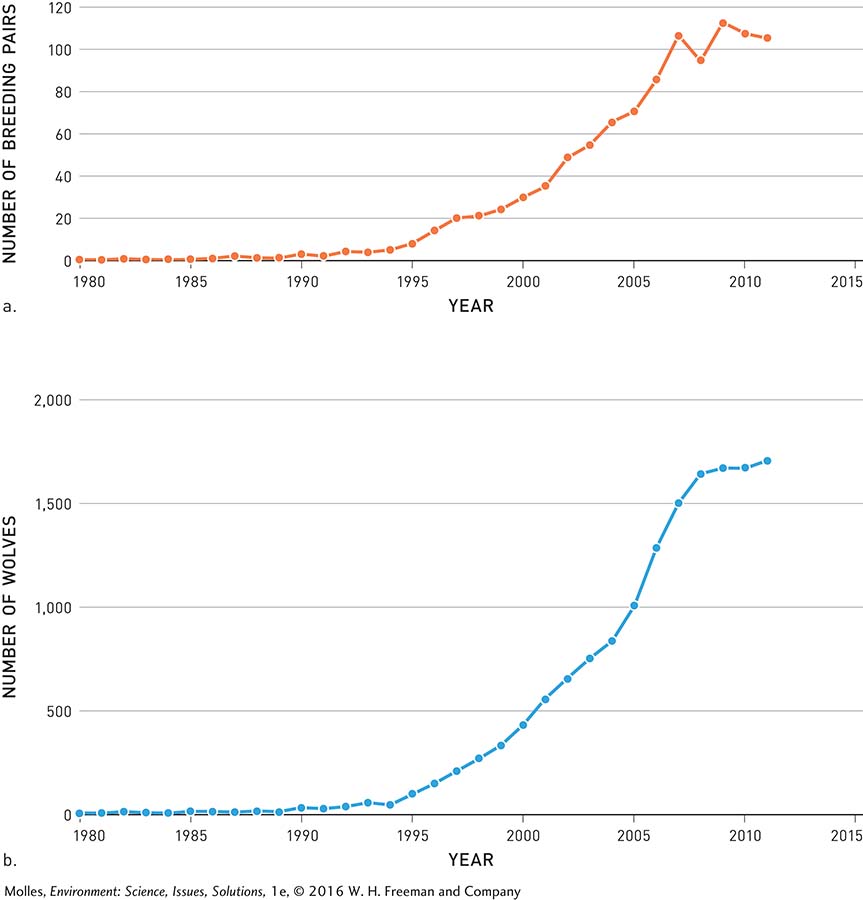

The wolf population of the Northern Rocky Mountains Recovery Area grew quickly following their reintroduction to Yellowstone and Idaho. Conservation biologists set a restoration goal of 30 breeding pairs, defined as a male and female that successfully rear at least two pups which survive to the end of the calendar year. That goal was met in 2000 and was quickly exceeded (Figure 3.30a). By 2007 there were over 100 breeding pairs across the Northern Rocky Mountain Recovery Area, which includes parts of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, and the number of breeding pairs appeared to be stabilizing, a pattern suggesting S-

In fact, the population grew to over 1,700 wolves by 2011 (Figure 3.30b), then dropped slightly to 1,600 individuals in 2013. Looking at just one part of the range, the Yellowstone wolf population peaked in 2003 at 172, then declined to fewer than 100 by 2009, where their numbers have approximately stabilized since. Again, the growth of the restored wolf population appears to be following an S-

Should restored gray wolf populations be subject to hunting and other forms of management control, or should they continue to receive protection as an endangered species?

Wolves remain a charged subject in Rocky Mountain states, where ranchers—

Think About It

How would population recovery for an r-

selected species, such as the Bay checkerspot butterfly (see page 67), likely compare to that of gray wolves? What aspects of gray wolf life history make it unlikely that any restored population will grow exponentially in the future?