3.13 Restoration of North American gray wolves has required working through conflict

Conservation success can sometimes introduce its own problems. In many cases, a species’ revitalization is inhibited by an environmental threat the peregrine falcon did not face: conflict with entrenched economic and cultural interests. Such is the case with the reintroduction of the wolf to Yellowstone and the surrounding area. The greatest opposition comes from livestock ranchers whose cattle may be attacked by wolves. One poll in the southern Rocky Mountains found that 53% of ranchers opposed restoration of wolves, while only 28% of nonranchers were opposed.

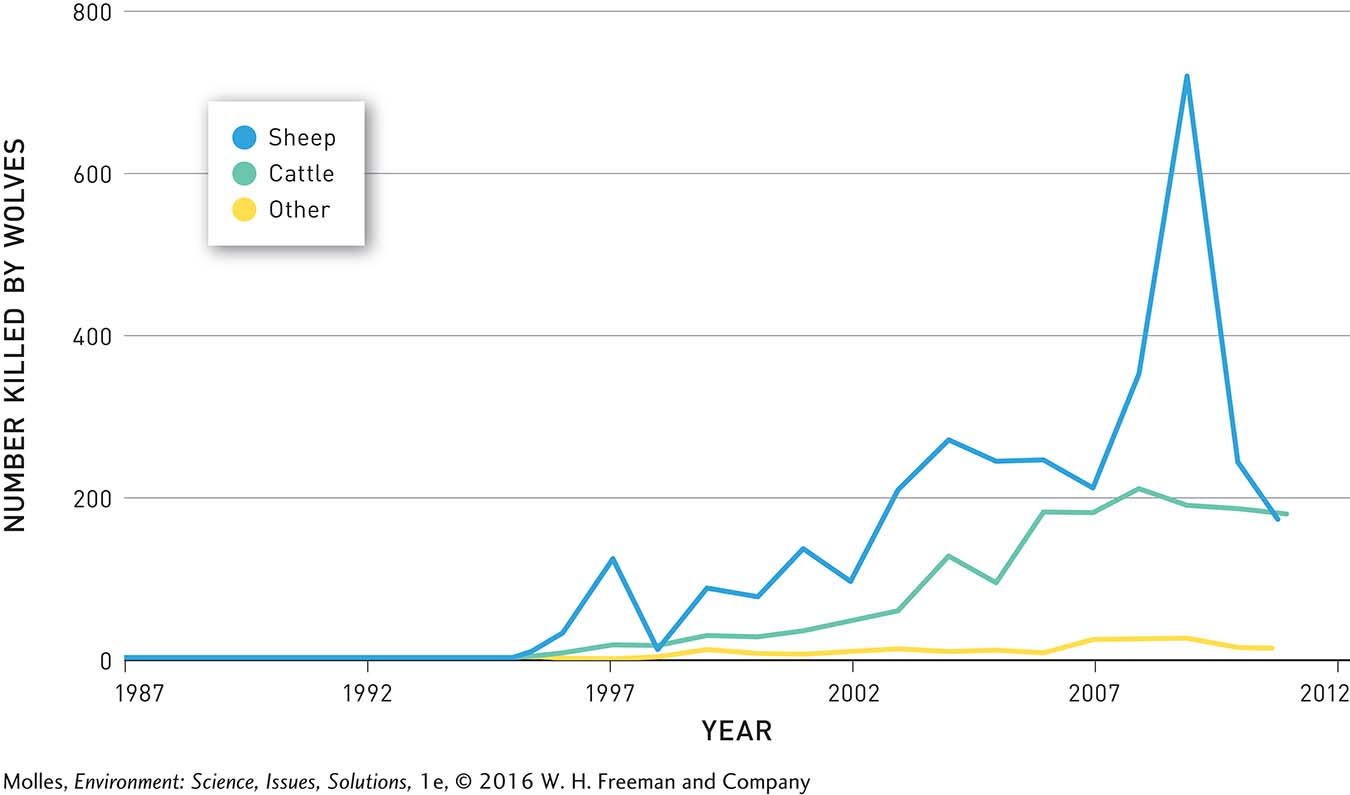

There is no doubt that wolves prey on livestock, especially cattle and sheep that are left unattended for long periods of time, and that ranchers could potentially suffer the economic consequences from this predation. In the 19-

What can be done to reduce the economic consequences of wolf restoration? The main mitigation strategy is to compensate ranchers for livestock losses. The Defenders of Wildlife, a nongovernmental organization, took the lead role in compensating ranchers for livestock lost to wolves. The position of the Defenders of Wildlife is that the loss of even a single animal to one rancher can be significant, and it established a fund of private donations for economic compensation. That fund, the Bailey Wildlife Foundation Wolf Compensation Trust, paid nearly $1.4 million in compensation to ranchers between 1987 and 2010, when compensation programs were transitioned to the states with wolf populations. Now that the states have taken responsibility for compensating livestock producers for losses to wolves, Defenders of Wildlife has begun to invest its resources into developing nonlethal ways to promote coexistence between livestock production and wolves (Figure 3.33).

Livestock production coexisted with wolf populations for thousands of years before modern traps, poisons, and firearms provided the means to exterminate wolves. What does this fact indicate about the possibility of coexistence in today’s world?

Think About It

Many ranchers graze livestock on public lands. Should public funds be used to eliminate predators on public lands to protect private livestock?

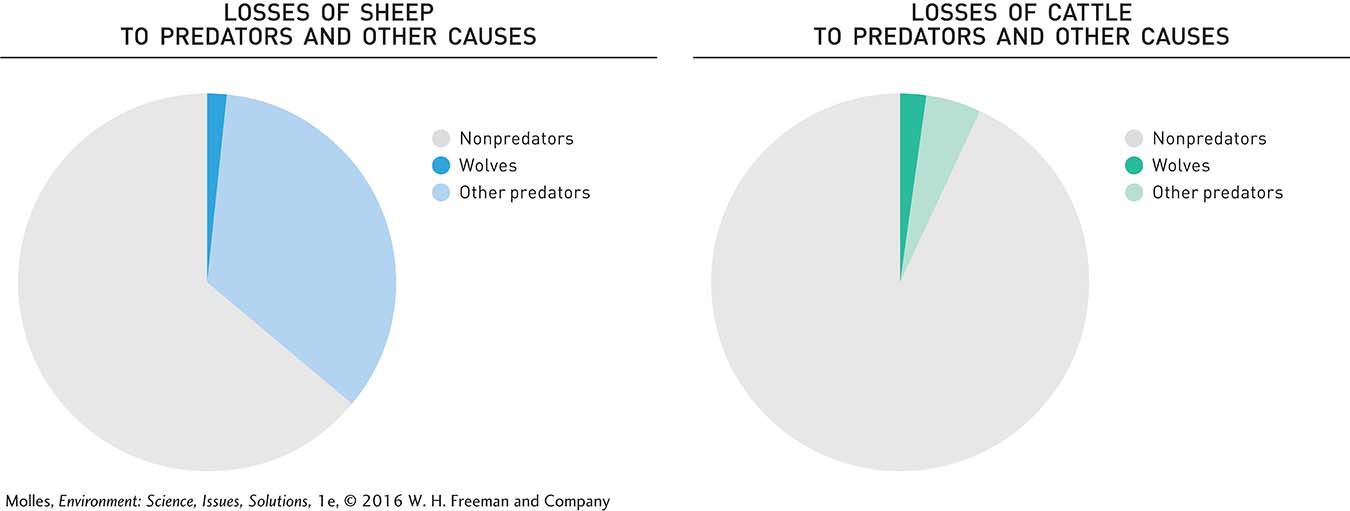

A published study of Mexican gray wolves living in Arizona and New Mexico found that 96% of their diet was based on wild prey, mainly elk and deer, and just 4% made up of cattle. How should we factor this information into an assessment of the threats that these wolves pose to cattle producers?

How should the economic burden of wolf restoration be spread across society?