3.4 The life history of a species influences its capacity to recover from disturbance

life history Characteristics of a species, such as the age at which individuals begin reproducing, the number of offspring they produce, and the rate at which the young survive.

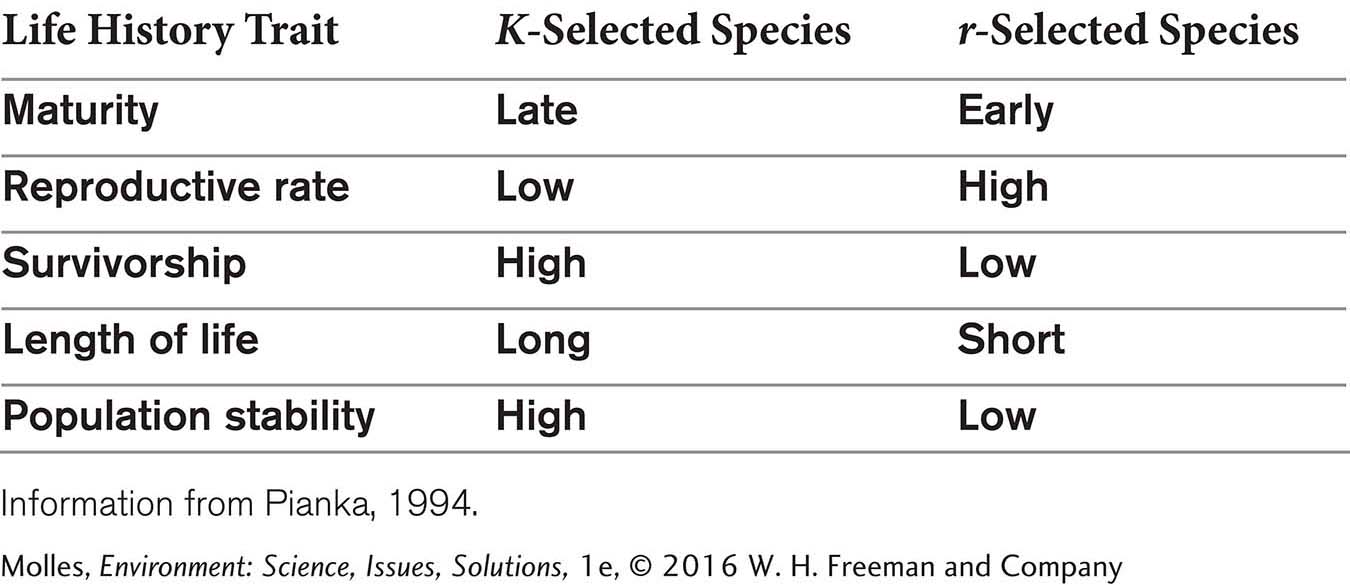

Some species’ numbers grow slowly and steadily and have stable populations over long periods of time, whereas others have populations that fluctuate wildly in response to changes in environmental conditions. Such differences are due to variation in life history among species, which includes such variables as the age at which individuals begin reproducing, the number of offspring they produce, and the rate at which the young survive.

K-

Whales, bears, wolves, and gorillas all have populations that can stabilize close to their carrying capacity, which is why we call them K-selected species. Ecologists propose that living near the carrying capacity favors individuals that excel at competing for limited resources in a crowded environment. These species have a long life span, tend to reproduce later in life, and have a small number of large offspring that receive intensive parental care. In general, density-

Can we classify all organisms as either r-

r-

Mice, rabbits, dandelions, and cockroaches are examples of r-selected species, which grow rapidly when the environment is favorable. You might sum up their philosophy as “live fast, die young.” Unlike large, enduring animals such as whales, r-

As humans alter the environment for our own benefit, what sorts of life histories among wild species are we favoring?

Let’s look closely at some animal and plant examples and see how the life history concept applies. Mountain gorillas, which are large and have low reproductive rates, are a perfect example of a K-

The concepts of r-

disturbance A discrete event (e.g., a fire, earthquake, or flood) that disrupts a population, ecosystem, or other natural system by changing the resources available or by altering the physical environment.

The life history of an organism influences its capacity to recover from environmental disturbances. Ecologists define disturbance as a discrete event, such as a fire, earthquake, or flood, that disrupts a population, ecosystem, or other natural system by changing the resources, such as food, nutrients, or space, available to organisms or by altering the physical environment. In general, populations of r-

Think About It

In terms of life histories, why are populations of K-

selected species generally slower to recover from disturbance compared with r- selected species? When studying life histories, why is it generally more informative to compare closely related organisms, for example, two primates, than to compare two very different organisms, for example, a primate and a tree or a primate and a butterfly?