3.6–3.9 Issues

On June 24, 2012, a century-

background extinction Average rate of extinction occurring over long periods of time between periods of mass extinction.

The disappearance of the Pinta Island tortoise is just one of many thousands of extinctions that have occurred during the course of human history. Although extinction is a normal process that takes place due to natural changes in climate, geology, and competition from other species, the current rate of extinction is between 100 and 1,000 times higher than background extinction levels.

mass extinction A period wherein a large proportion of species becomes extinct within a few million years or less.

Over the course of the history of Earth, there have been five great mass extinctions, in which a large proportion of species became extinct within a few million years. An estimated 99% of species that once existed are now extinct. The last great extinction, which was possibly caused by an asteroid strike, wiped out the dinosaurs, along with 75% of all species, about 65 million years ago. An earlier mass extinction, 245 million years ago, resulted in the extinctions of about 90% of species on Earth.

Anthropocene era A new geologic era dominated by the effects of humans.

The current rate of extinction, estimated at up to 1,000 times higher than background levels, is high enough to be considered a mass extinction. Environmental scientists estimate that at present rates of extinction, we are now experiencing the sixth mass extinction. We are on course to lose approximately half of all species on Earth by the end of the 21st century. In contrast to previous extinctions, the sixth mass extinction is not the result of an asteroid or a comet but rather one of Earth’s most abundant large vertebrate species: Homo sapiens. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN, the former World Conservation Union) estimates that 99% of all species threatened with extinction are at risk because of human activities. For this reason, some scientists argue that beginning in 1945, when the first nuclear bomb was dropped, we entered an entirely new era: the Anthropocene, a new geologic era dominated by the effects of humans. Perhaps the most dramatic evidence of the reality of the Anthropocene are human impacts on global climate (see Chapter 14), another factor that will undoubtedly contribute to the unfolding mass extinction caused by our species.

3.6 Habitat destruction and alteration are the most serious threats to biodiversity

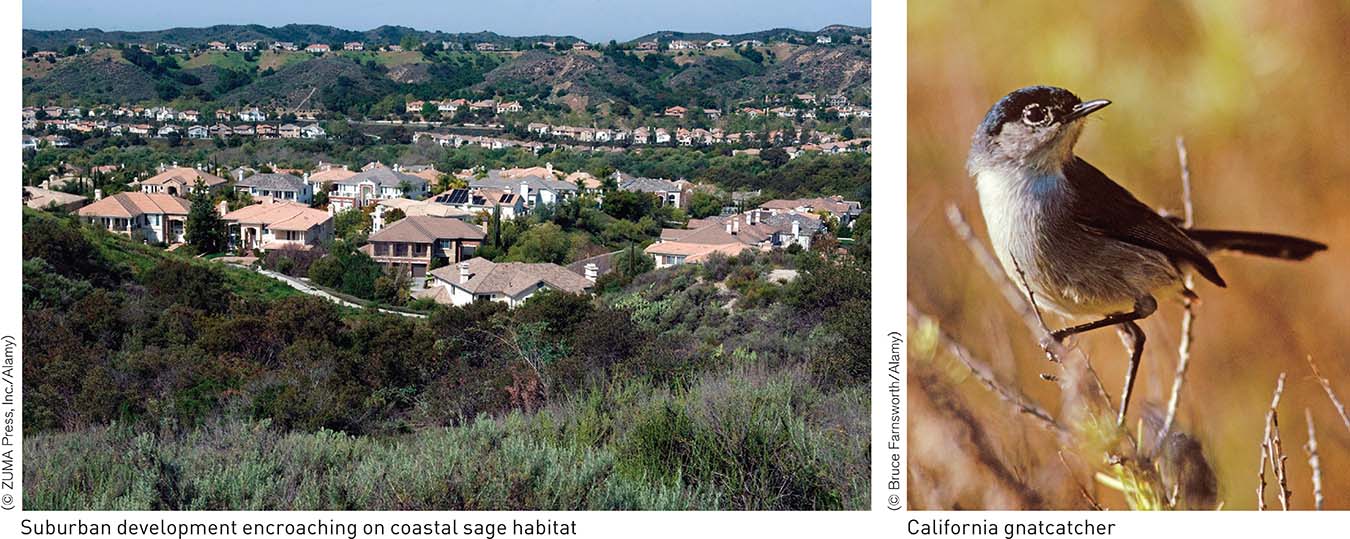

Habitat destruction is, without a doubt, the greatest threat to biodiversity around the world. The human population, which surpassed 7 billion in 2012, increasingly dominates Earth. As our population grows and we alter the planet to meet our own needs, we put untold thousands of species at risk. In Chapter 4, we will consider how human impacts on the environment challenge the diversity of whole communities of organisms. Consider the extensive agriculture and urban sprawl in southern California coastal sage scrub. The region, home to 300 plant species found nowhere else, once covered approximately 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres). Today, as little as 10% of that remains. Native mammal and bird species, such as the California gnatcatcher, have been largely restricted to remnants of their habitat. Many of these small populations are unable to sustain themselves and will likely die out within a short period of time (Figure 3.20).

Why is habitat destruction considered one of the most serious threats to species’ populations?

We destroy terrestrial habitats when we plow prairie and plant wheat, cut down a tropical rain forest, or drain and fill in marshes. With each pass of a bulldozer, we reduce the habitat available for other species, thereby reducing their total population size. In these situations, smaller, isolated populations, such as butterflies or mountain gorillas, have a lower chance of survival than larger populations. According to the IUCN, habitat loss and degradation are affecting 86% of all threatened birds, 86% of threatened mammals, and 88% of threatened amphibians.

Environmental scientists estimate that we are losing approximately 90,000 km2 of tropical rain forest annually, which is approximately the area of the state of Indiana. In the countries of Southeast Asia, including Malaysia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea, approximately 11 million hectares of tropical forest have been cleared for oil palm plantations. Palm oil is used in foods, beauty products, and even as a biofuel. One casualty of this transformation has been the orangutan, a great ape that spends most of its life high in the tree canopy on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. The orangutan population has declined by 50% since the 1950s. If current trends continue, conservationists believe that the Sumatran population could vanish in the next 10 years and that the Bornean population is unlikely to survive into the next century.

The typical focus of conservation efforts is on large, impressive species, such as Siberian tigers or Kermode bears. How does this help or hinder the conservation of ecosystems?

Temperate habitats are also under threat. More than 50% of historic grasslands and more than 30% of desert habitat have been lost. The Kermode (or spirit) bear, a white subspecies of the black bear, is one temperate species that is seriously threatened by habitat destruction. The bear lives in the temperate rain forests of northwest Canada (Figure 3.21). The bear’s habitat is shrinking due to the logging of old growth forests in the region and will shrink even further as a result of a recently approved project to build an oil pipeline on Princess Royal Island in British Columbia.

Marine and freshwater species are also increasingly impacted by human activity. According to the IUCN, freshwater species are going extinct faster than either terrestrial or marine species. In 2014 the IUCN estimated that human pressures on freshwater ecosystems threatened one-

Think About It

What factors likely contribute to the greater vulnerability of freshwater species to extinction, compared with the vulnerability of terrestrial and marine species?

Does a growing human population inevitably produce habitat destruction? What other factors besides our population growth contribute to habitat destruction?