3.7 Invasive species threaten native species

Will the relative rate of infection of invasive non-native species by parasites and pathogens remain constant in their new environment over the long term? Why or why not?

After the brown tree snake arrived on the island of Guam following World War II, 10 out of the island’s 12 native forest bird species went extinct—all fallen prey to a predator they neither recognized nor had learned to fear. The brown tree snake is what we call an invasive species, one that, when introduced to a new environment, poses a serious threat to native populations. Increasing globalization, including the rise in airline travel and transportation of goods on giant cargo ships, is increasing the movement of species across Earth.

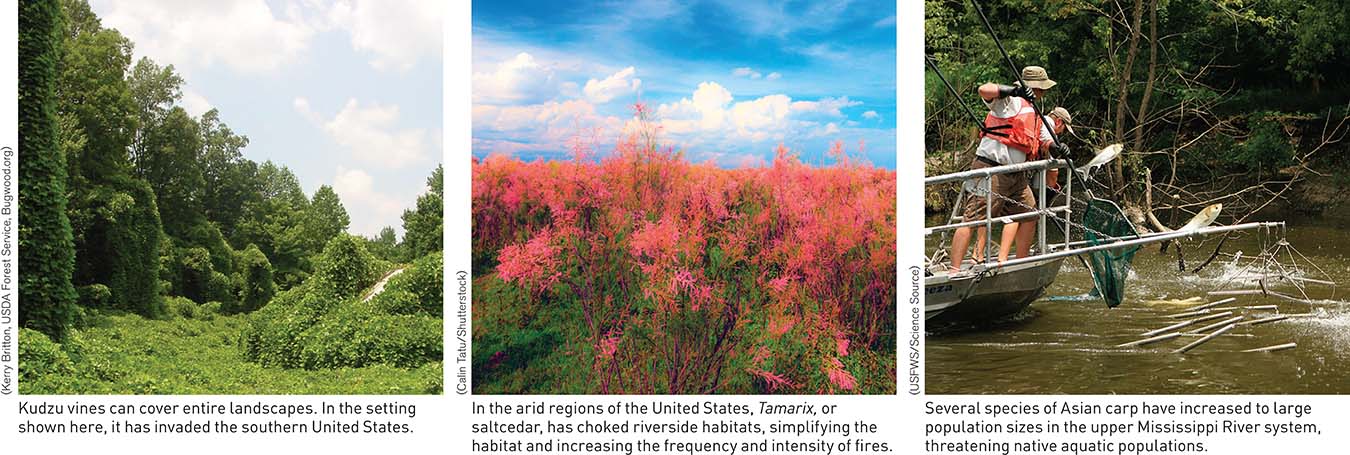

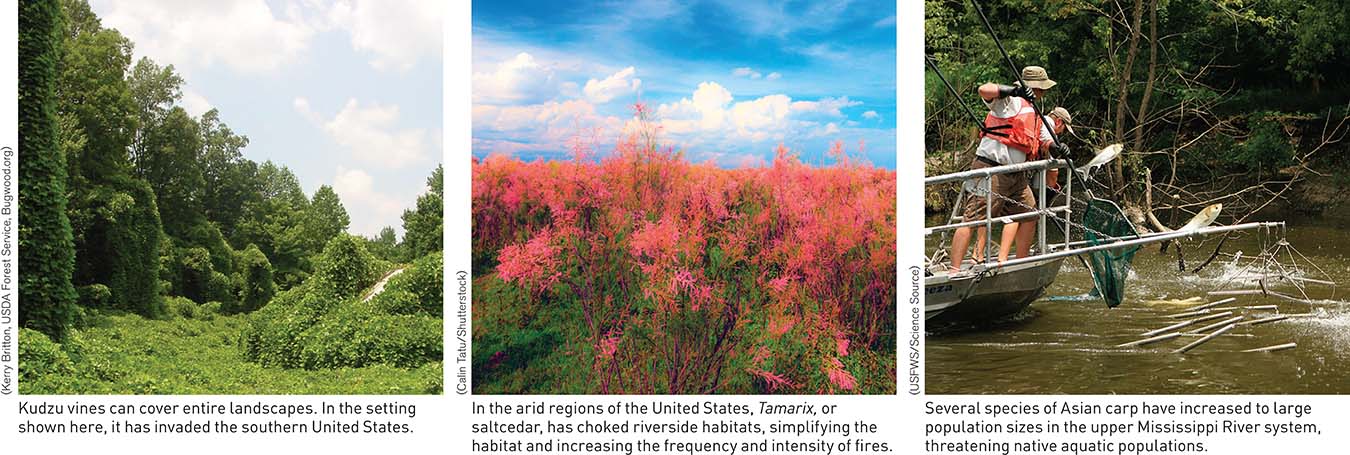

Invasive species may be predators, as in the case of the brown tree snake, or they may be pathogens or competitors. Introduced species often compete fiercely with native species because they are not hindered by their own predators, parasites, and pathogens (see Table 3.1, page 71). As a result, non-native species can become overwhelmingly abundant in their new environment and competitively displace native species (Figure 3.22).

INVASIVE COMPETITORS

FIGURE 3.22 Released from predators, parasites, and pathogens present in their native environments, populations of invasive species can grow explosively in a new environment, overwhelming native species in the process.

(Kerry Britton, USDA Forest Service,

Bugwood.org) (Calin Tatu/Shutterstock) (USFWS/Science Source)

The cane toad is an invasive species that has hurt biodiversity in Australia in an unexpected way. Here’s what happened: Sugarcane farmers introduced the softball-sized cane toad, hoping the toads would eat beetles that infested the sugarcane crop. The toads proved to be a weak beetle-controlling mechanism. But the bigger problem was their effect on animals besides beetles. The cane toad secretes a toxin from glands on the back of its head. In South America, where the toad is native, predators had either evolved resistance to the toxin or knew to stay away from the cane toad. In Australia, however, monitor lizards and endangered carnivorous mammals known as quolls had no resistance to the toad’s toxin and simply saw it as an easy meal. So far, it has caused serious declines in species’ populations. It remains to be seen how well Australian animals will recover and adapt to the toads’ presence in the future.

Introduced species can have indirect effects as well. Invasive plants have pushed the Bay checkerspot butterfly to the brink of extinction largely by altering the makeup of the native grasslands of California. Similar stories are repeated around the globe, which is why the World Resources Institute, an environmental think tank dedicated to finding ways to protect the environment and improve people’s lives, cites invasive species as the second greatest threat (after habitat destruction) to endangered species.

Page 79

Think About It

How may similarity in niches affect competitive interactions between native and invasive species?

What sorts of evolutionary pressures do invasive predators and competitors exert on the native species with which they interact?