4.12 Integrating conservation with local communities can help sustain protected areas

What economic activities should be allowed in each of the zones pictured in Figure 4.31? Which should be prohibited?

One of the most serious threats to protected areas is encroaching development in surrounding areas. As the environment surrounding a protected area becomes increasingly degraded and fragmented, the protected area itself becomes an increasingly isolated habitat (Figure 4.30). In addition, many protected areas are further compromised when local people illegally remove plants and animals from the protected area itself. However, such problems have been reduced substantially where managers and residents of surrounding communities work cooperatively. Such cooperative relationships arise where local communities derive clear economic benefits from the protected area and its surroundings.

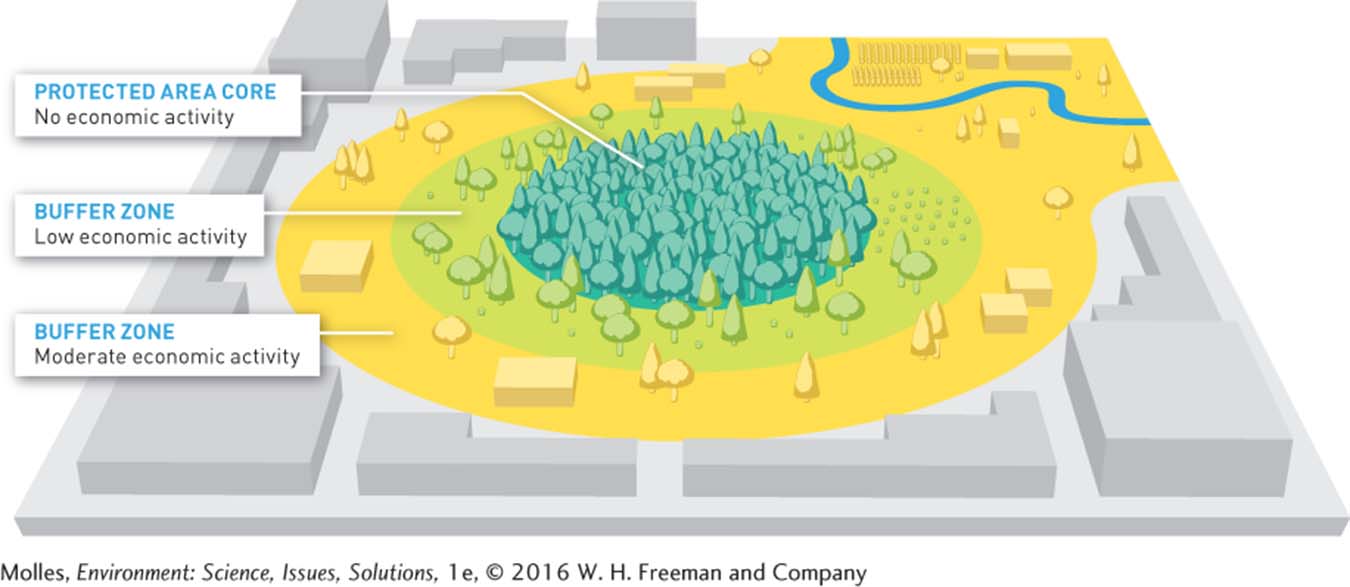

buffer zone A zone around a nature reserve or protected area in which limited economic activity is allowed.

One method of ensuring these direct benefits is to establish buffer zones around the core of a protected area in which the local community can pursue a number of economic activities, such as harvesting of wood, fishing, and some agriculture, while highly restricting activity in the core of the protected area (Figure 4.31). Involving the local community in the management of protected areas can yield additional benefits.

Community Integration Provides Protection

The Guanacaste Conservation Area in Costa Rica provides a model for the integration of a protected area with the local community. Situated in the dry tropical forest on the Pacific coast, Guanacaste has more than 100 full-

The Guanacaste Conservation Area has also taken creative approaches to protecting the preserve by employing known poachers as game wardens, as well as known fire-

Looking Beyond the Boundaries

Protected areas can be threatened by events taking place far away. For example, toxic chemicals dumped in the water can decimate freshwater and marine populations in distant protected areas. Toxic gases and pollutants can drift from industrial and urban areas into parks. Carbon dioxide emitted in one country can alter global temperature and precipitation patterns all over the world, threatening all protected ecosystems on Earth.

Protecting natural ecosystems and the biodiversity they sustain is a key to sustaining Earth’s biodiversity. However, protected areas cannot be sustained as islands of exceptional biodiversity in a matrix of degraded ecosystems. The long-

Think About It

What dangers to biodiversity conservation may occur if human communities are allowed unrestricted access and use of the protected areas?

What are the dangers if protected areas are completely isolated from human communities?

What would be a viable middle ground regarding protection versus use of biodiversity reserves?

What are the implications of global climate change to the functions of protected areas over the long term?

4.9–4.12 Solutions: Summary

The Convention for Biological Diversity set the stage for efforts to protect ecosystems and their biodiversity. Protected areas are a key part of this solution, and today there are more than 100,000 of them across the globe. A second key to effectively conserving Earth’s biodiversity is involving a broad range of stakeholders, including local communities and NGOs such as The Nature Conservancy. Sustaining biodiversity requires not only the establishment of protected areas, but also management through maintenance of keystone species, regulation of the fire regime, and control of invasive species. In many situations, sustaining the biodiversity values of protected areas may be enhanced by integration with human communities beyond their boundaries.