4.6–4.8 Issues

It’s fair to say that no place on Earth has been left untouched by human activity. In places like Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, there’s almost no trace of Minetta Brook, which once flowed into a marsh where Washington Square Park now sits. The wildlands of the western United States are crisscrossed with roads cut by ranchers, loggers, and oilfield workers. Even deep within the Amazon, evidence of ancient metropolises can be seen in soil charcoal patterns and irrigation canals. And even in ecosystems where humans have never set foot, our carbon-

4.6 Habitat fragmentation reduces biodiversity

habitat fragmentation

A subdivision of a formerly continuous habitat into isolated habitat patches as a result of activities such as deforestation, road building, and dam construction on rivers.

How would ecological succession (see page 106) generally affect forest fragmentation?

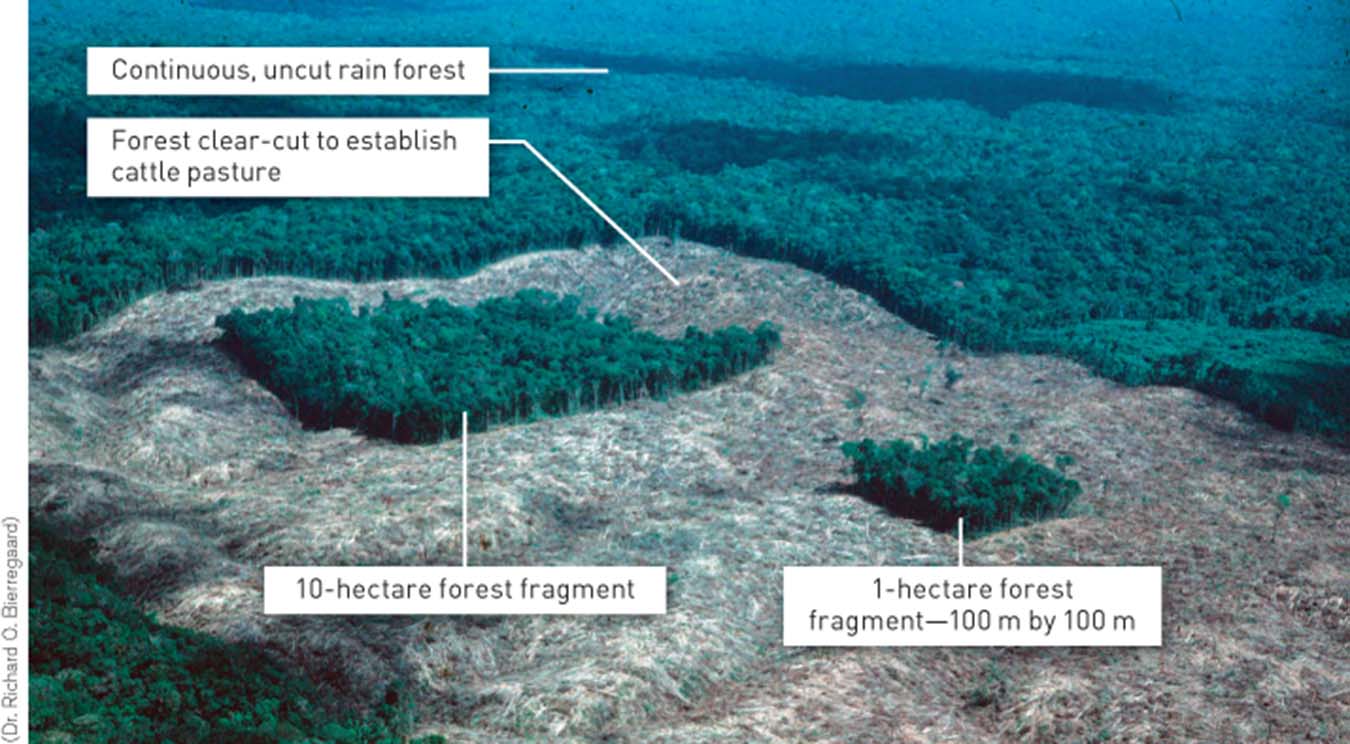

Every time we clear land for roads or farms, build subdivisions, or excavate a mine, we break up natural ecosystems. Habitat fragmentation transforms continuous ecosystems into smaller, increasingly isolated patches of habitat, or habitat fragments. A patch of forest surrounded by a large area of land cleared for cattle pasture is a typical example. Habitat fragmentation affects the entire community of organisms and can reduce species richness because the populations of species dependent on the remaining patches of native ecosystem are generally reduced and their long-

Tropical Forest Fragmentation

In addition to the 90,000 km2 of tropical forest that is cleared annually, some 20,000 km2 are not entirely destroyed each year but rather damaged by logging, burning, and road building, resulting in habitat fragmentation (Figure 4.19). For the last three decades, the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project, a cooperative effort by Brazilian scientists and others from all over the world, has been investigating this phenomenon. Within a 1,000-

Was there ever a time when tropical forest interior species may have been more common than tropical forest edge species?

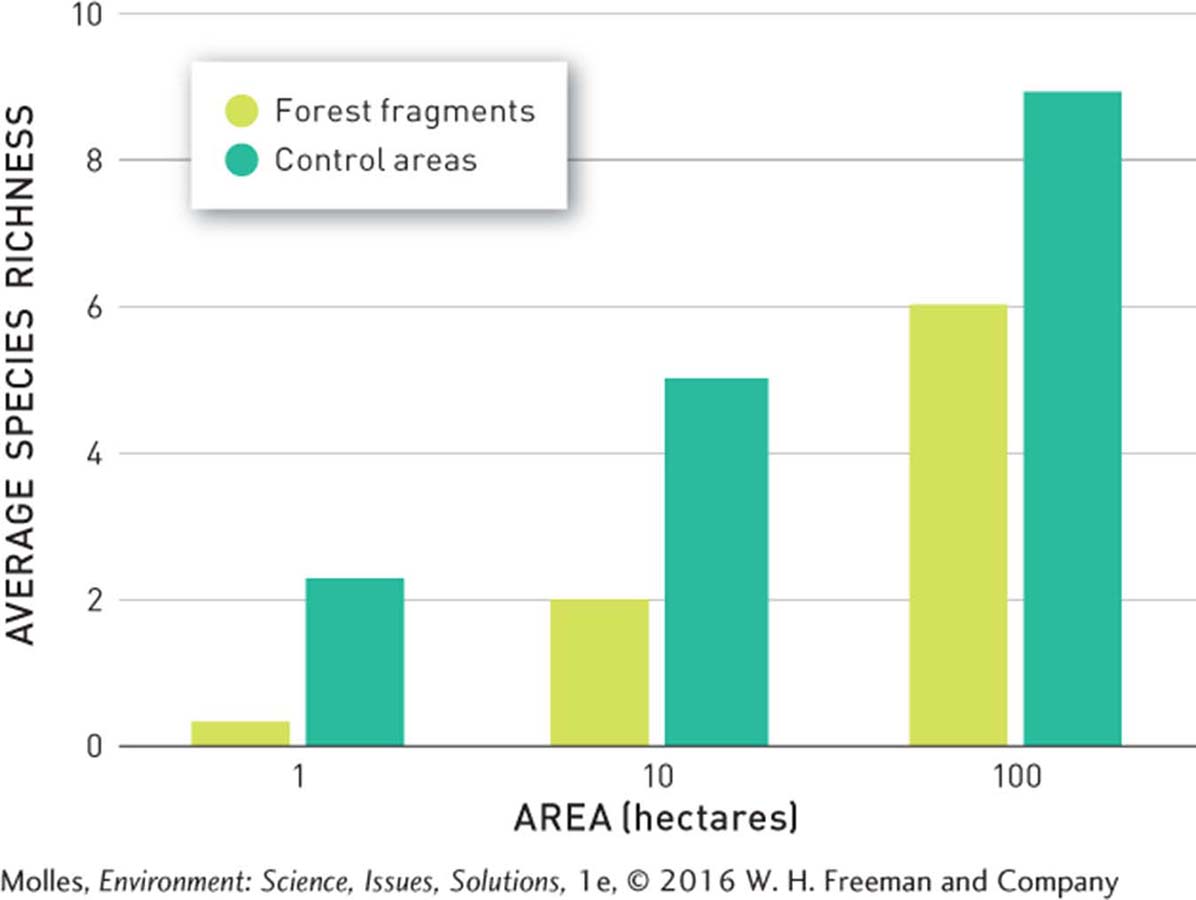

The results of the study, which have been reported in hundreds of scientific papers, are clear: Compared with larger fragments, smaller forest fragments support fewer species of large mammals, primates, understory birds, dung beetles, ants, bees, termites, and butterflies. Most significant, forest fragments of all sizes support fewer species of forest animals compared with similar-

Edge Effects

edge effects Environmental conditions occurring near the edge of an ecosystem (e.g., near the edge of an isolated forest fragment); conditions at edges differ from those deep in the ecosystem interior.

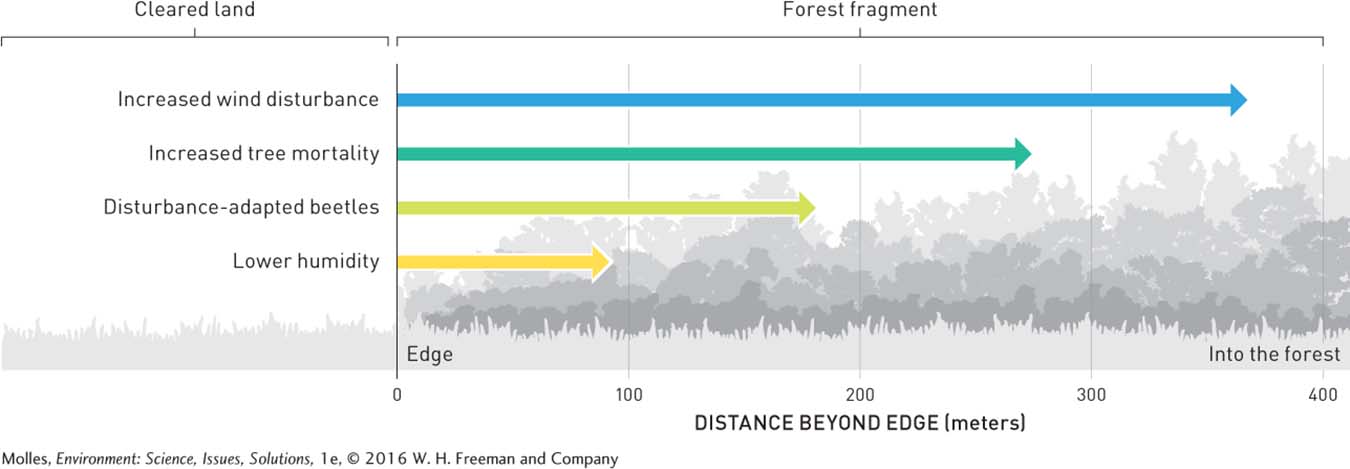

When considering the size of an isolated fragment of forest, it’s important to remember that the newly created edge of that patch is different from the interior. Edges may be windier, drier, and hotter and might be subject to more insect pests. These edge effects often extend deep into the patch of forest. In the Amazon River Basin, 30 different edge effects have been identified, extending as far as 400 meters (1,300 feet) into forest fragments (Figure 4.22). While some species thrive where fragmentation produces edge effects, those that require the physical conditions of the interior of an ecosystem (e.g., higher humidity or lower sun exposure) do not. Consequently, as edge conditions proliferate with increasing fragmentation, these “interior species” decline in abundance and at some point disappear from the landscape.

Think About It

What are some ways to counteract the effects of isolation that result from habitat fragmentation?

How are habitat patches—

for example, forest patches surrounded by agricultural fields— and oceanic islands similar? How are they different?