4.8 Many invasive species harm ecosystems

We already learned in Chapter 3 that invasive species can endanger populations of native species. However, the impacts of invasive species can extend to entire ecosystems. The Fynbos vegetation of South Africa is one of Earth’s biodiversity hotspots, where rolling green meadows border the southern Indian Ocean. Unfortunately, invasive pine and acacia species in the Fynbos have sucked so much water out of the ground that they have reduced water flow in nearby river basins by nearly one-

Is it sometimes appropriate to consider invasive species problems as threats to public safety and security in addition to associated ecological issues?

fire regime The frequency and intensity of fires that typically occur in a particular ecosystem.

Woody invasive plants have also increased the intensity of fires by increasing the amount of flammable plant biomass in the ecosystem. In the southwest United States, a thirsty tree called saltcedar, Tamarix species, has dried up streams and changed the fire regime by increasing the frequency and intensity of fires in these ecosystems. Similarly, cheat grass, Bromus tectorum, which has invaded vast areas in western North America, not only increases fire frequencies but also is a poor source of forage for livestock or native animals. Prior to the cheat grass invasion, wildfires occurred every 60 to 110 years; now they happen every 3 to 5 years (Figure 4.23).

Invasive Species and Aquatic Ecosystems

How does one weigh the loss of hundreds of fish species found nowhere else on Earth against establishing the highly profitable Nile perch fishery in Lake Victoria, the largest lake fishery in the world?

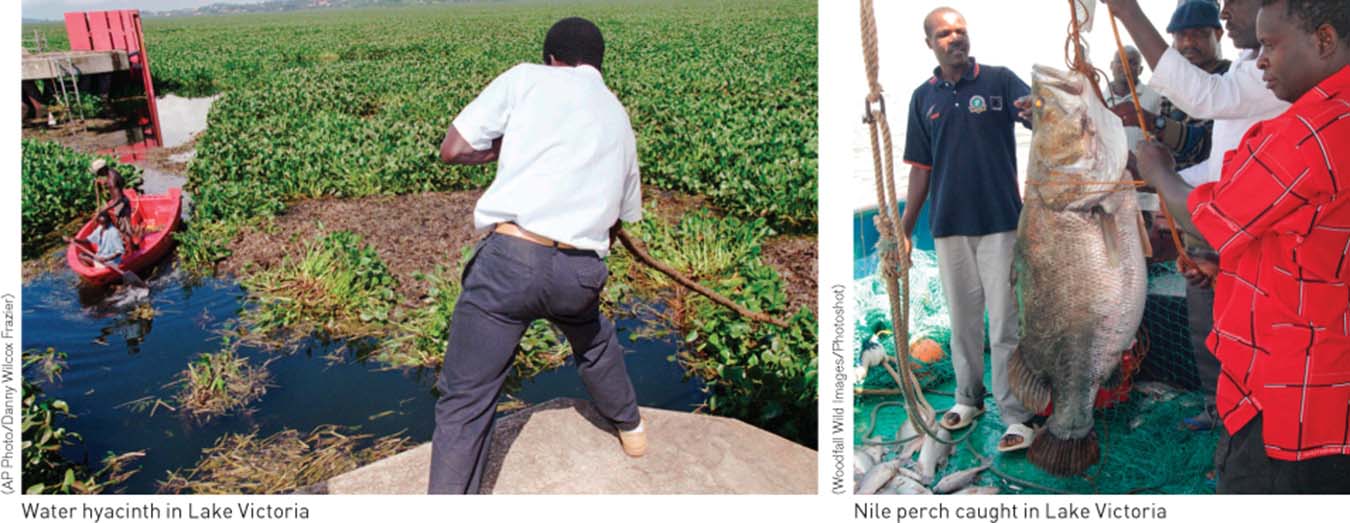

The impact of invasive species is not limited to terrestrial environments. Invasive aquatic species have been spread around the world with devastating consequences to ecosystem goods and services. Countries across Africa spend millions of dollars each year to control invasive aquatic weeds that choke waterways important for fishing and commerce. The introduction of the Nile perch into Lake Victoria, one of the great lakes of Africa, has resulted in hundreds of native fish species going extinct (Figure 4.24), but it has also had consequences for the ecosystem as a whole. For instance, local people once caught smaller native fish, which they could sun-

In Asia, the golden apple snail has ravaged rooted aquatic plants, reducing their biomass and releasing nutrients into the ecosystem. As a result, previously clear waters are now turbid and choked with algae. In the United States and Canada, zebra mussels have become a nuisance by attaching to nearly any submerged structure, including the intakes to water supply systems.

Economic Impact of Species Invasion

The executive director of the United Nations Environmental Programme estimated that the costs of invasive species to the global economy exceeded $1.4 trillion in 2010. The economic costs of controlling just the saltcedar invasion of western North America have been estimated at $127 to $291 million annually for control and estimated water losses. Meanwhile, zebra mussel control associated with water systems around the Great Lakes approaches $70 million each year. However, some invasive species exact even greater costs. For instance, the water losses resulting from invasive species in the Fynbos region are valued at $1.4 billion, and the golden apple snail, introduced from South America, causes over a $1 billion in annual losses in rice cultivation in the Philippines. David Pimentel and colleagues from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell University estimated that as of 2005, invasive species have caused over $120 billion in damages annually in the United States alone.

Think About It

During control efforts, do we have an obligation to treat invasive species, especially vertebrate animals, ethically?

Does the use of militaristic terminology (e.g., battle, eradicate, overrun, and kill) to frame relationships with invasive species foster an adversarial relationship with nature rather than a sustainable one?

4.6–4.8 Issues: Summary

Habitat fragmentation, which transforms continuous ecosystems into smaller, isolated habitat patches, results in significantly reduced biodiversity. Increased wind or reduced moisture on the edges of ecosystem patches gives them a smaller effective size than they appear on a map. Ecological economists estimate that the total value of goods and services provided by natural ecosystems, including maintenance of biodiversity, may be $125 trillion, or nearly twice the total global annual gross product. Many ecosystem services are threatened by habitat destruction and the spread of infectious diseases, such as white nose syndrome in bats. These services are not only valuable, but they can also save human lives by reducing coastal storm surges, reducing forest fires, and providing clean water. Invasive species can also harm ecosystems by altering hydrologic and fire regimes. The economic impacts of invasive species, which amount to hundreds of billions of dollars annually, result from control costs and reduced ecological services.