5.8–5.10 Solutions

How might cultural and ethical considerations help or hinder efforts to control population growth? Give specific examples.

A conversation about unsustainable population growth represents an opportunity to preserve the environment and improve people’s lives. Consider that in southern Somalia, young girls get married in their teenage years and start having children almost immediately. Across Africa, women have an average of six children. The lives of these women are almost entirely consumed by childbearing, cooking, cleaning, and water collection. That means there’s no time for education or entrepreneurship. There’s little chance to advance in their lives or to give their children more options than they themselves had.

Having a large family is, of course, a personal choice, which is one reason why population growth remains one of the most daunting and controversial environmental challenges of our day. Nevertheless, when countries design ethical policies to encourage population stability, everyone has a chance to benefit.

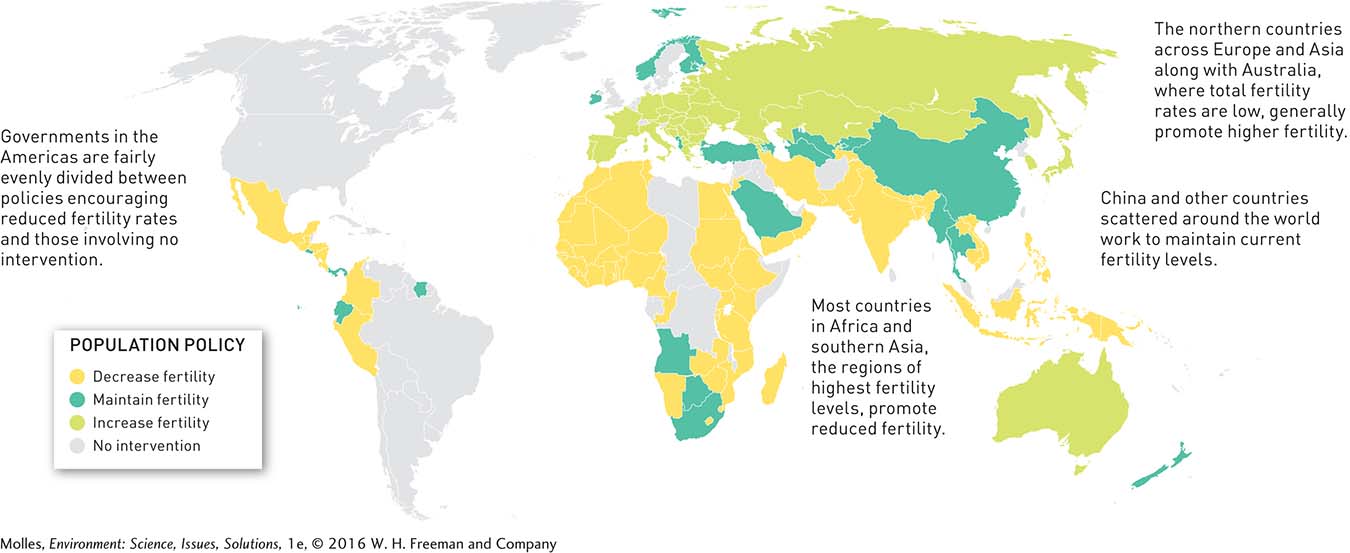

5.8 Most nations have national policies aimed at managing population growth

The problem of high fertility rates is not limited to sub-

The Historical Norm: High Fertility Rates

The lack of effective contraceptives in the past is one of the major reasons why family size has historically been so large. But there are also good reasons why people have wanted to have large families. Poor nutrition, sanitation, and health care meant that many children would die shortly after birth or at a very young age. Large families provide a hedge against loss of children to disease and accidents. As you probably know from growing up, children are a free source of labor to their parents. They can do chores such as tending crops and livestock, and they can help sell goods at the market. As parents and grandparents age, children can help take care of them.

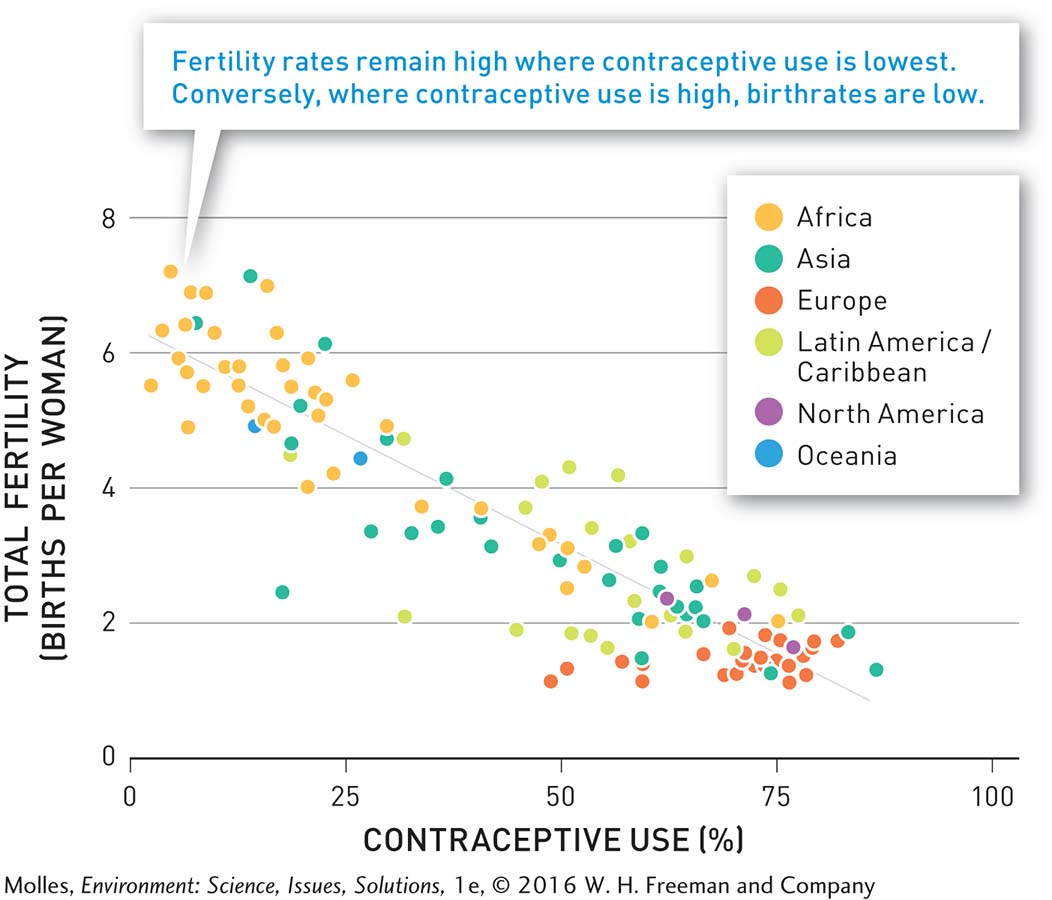

Access to Contraceptives and Birth Rates

Today, birth control pills, condoms, sterilization, and other forms of contraception are a key element in most national programs for reducing population growth. The United Nations encourages the use of contraceptives to reduce birthrates where population growth is rapid. Abortion of unwanted and dangerous pregnancies, though controversial, also plays a role in some programs. The UN has stated, “All couples and individuals have the basic right to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children and to have the information, education, and means to do so.” The United Nations recognizes the importance of controlling population growth in a manner that respects local laws and customs and encourages all countries to provide “universal access to a full range of safe and reliable family-

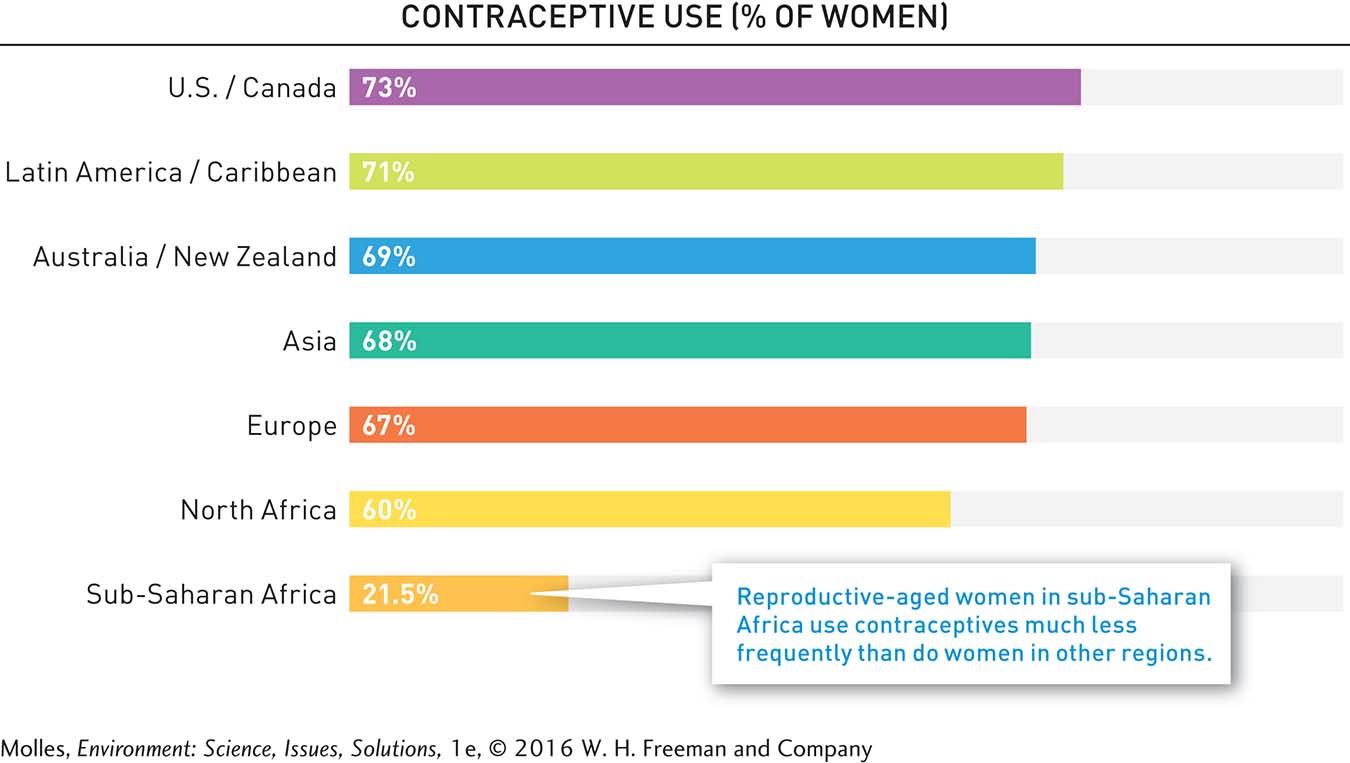

In a 2007 study, the United Nations found that contraceptive use varies little among most world regions (Figure 5.20). Worldwide, the range of contraceptive use by reproductive-

Let’s examine the history of two countries that have invested heavily in population planning. Two of the most prominent examples of national population policies are those of India and China, home to over 35% of the global population.

India: A Pioneer in Population Policy

Concerned that India’s economic development would be disrupted by the rapid growth of its population, India developed the world’s first national policy on population in 1952. Under India’s National Population Policy, the government provides all citizens with the information and means to make informed choices regarding childbearing. However, participation in any family-

Though available funds have been inadequate to entirely meet the goals of its population policy, India has made remarkable progress over the past half-

China’s One-Child Family Policy

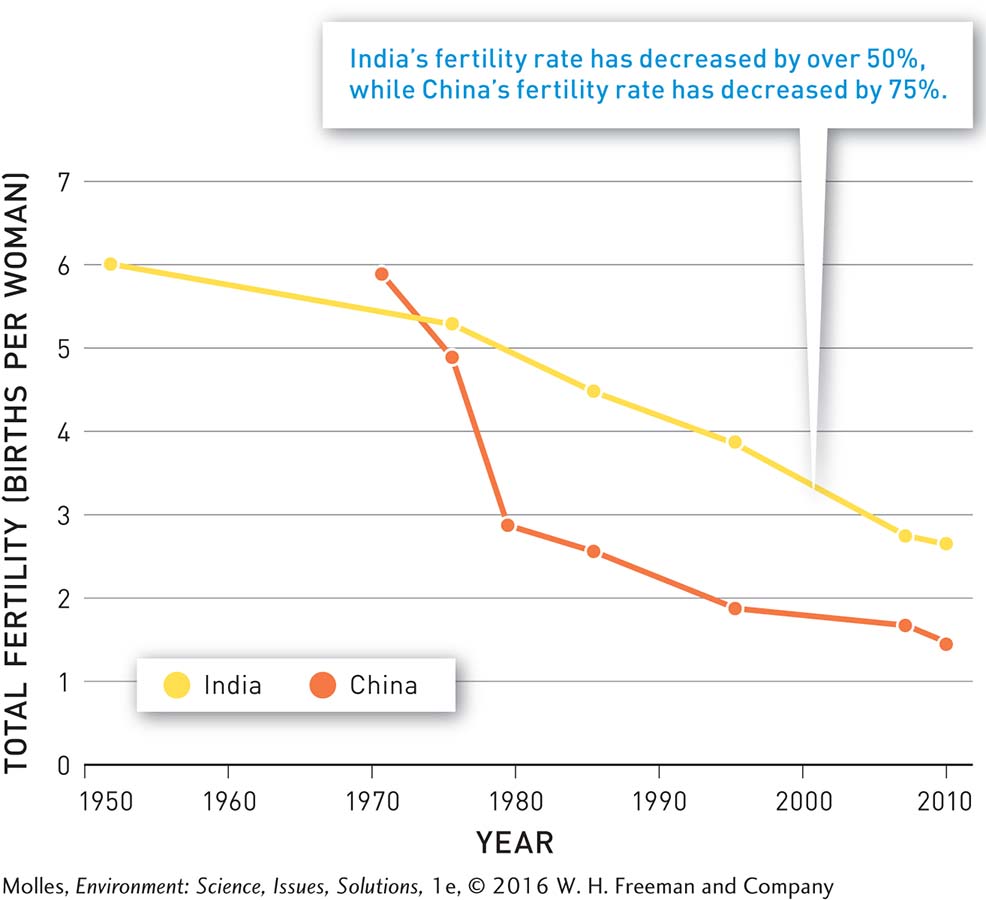

In 1970 the Chinese government introduced a voluntary program that simply encouraged smaller families. However, its population continued to swell, and by 1979 China was home to nearly one-

The one-

The program had dramatic impacts on China’s population dynamics (see Figure 5.23). The total fertility rate in China, which averaged 5.9 children per woman in 1970, fell to 2.9 during the period of voluntary family planning. However, following the establishment of the strict one-

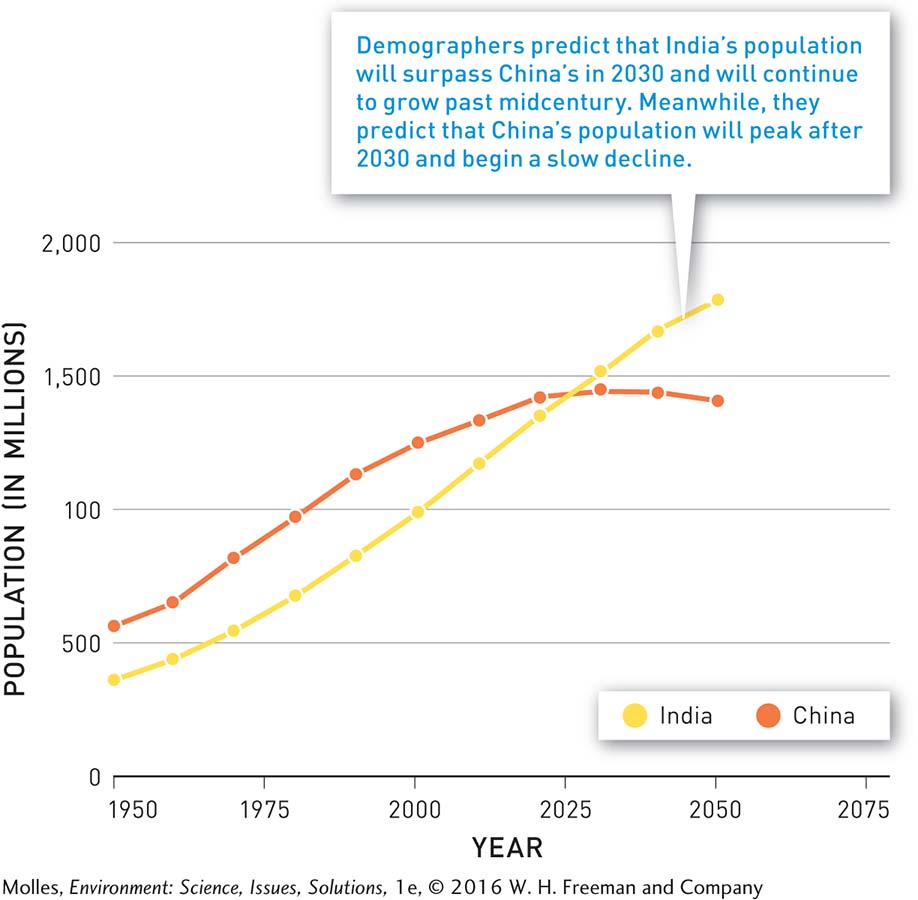

Demographers predict that China’s population will peak sometime after 2030 and begin declining thereafter. In contrast, India’s population is projected to continue growing past mid-

China has been gradually loosening its infamous policy. In 2013 it began allowing a second child when one of the parents was an only child. Previously, both parents had to be an only child in order to qualify. Then, in late 2015, it adopted a blanket two-

The Missing Daughters

sex ratio at birth The ratio of male to female newborns.

The natural sex ratio at birth of human populations, defined as the ratio of male to female newborns, is about 103 to 107 male births for every 100 female births. In other words, there are 3% to 7% more male births than female births. This imbalance evens out with age to a ratio of approximately 100 males to 100 females in the population. That’s because males at all ages are more likely to die from disease and accidents. Recently, however, sex ratios at birth have become highly biased toward males in a number of Asian populations.

The prejudice among parents in North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia is that sons are more valuable than daughters. People in these regions believe that sons are better able to do agricultural work and are more capable of supporting aged parents. They are also, by custom or law, the inheritors of family property and can continue the family line. Today, even as the historical justifications for this bias have faded, families continue to prefer sons, a quest that has been assisted through sex-

How would you react if your government attempted to restrict your reproductive rights?

An imbalance in the proportions of males and females may be one of the unforeseen outcomes of China’s one-

Countries across Asia have become alarmed about unbalanced sex ratios. Young men in China, concerned by their limited marriage prospects, sometimes take organized tours to neighboring countries, such as Vietnam, in search of a mate. Policy makers fear that populations with millions of single males with no prospects for marriage and family may lead to more violence and social instability. In response, several Asian countries, including India and China, have outlawed prenatal sex screening and sex-

How might male-

In addition, China has produced public awareness campaigns aimed at warning of the social dangers of an imbalanced sex ratio and extolling the inherent value of a child of either sex (Figure 5.25). Public attitudes appear to be changing in China, where recent surveys have indicated that 37% of women expressed no preference for a son or daughter, and equal numbers, about 6%, preferred either a single daughter or a single son. The remainder of those surveyed said that their ideal family would include one son and one daughter. In India, similar campaigns have begun to reduce sex-

Global Trends in Fertility

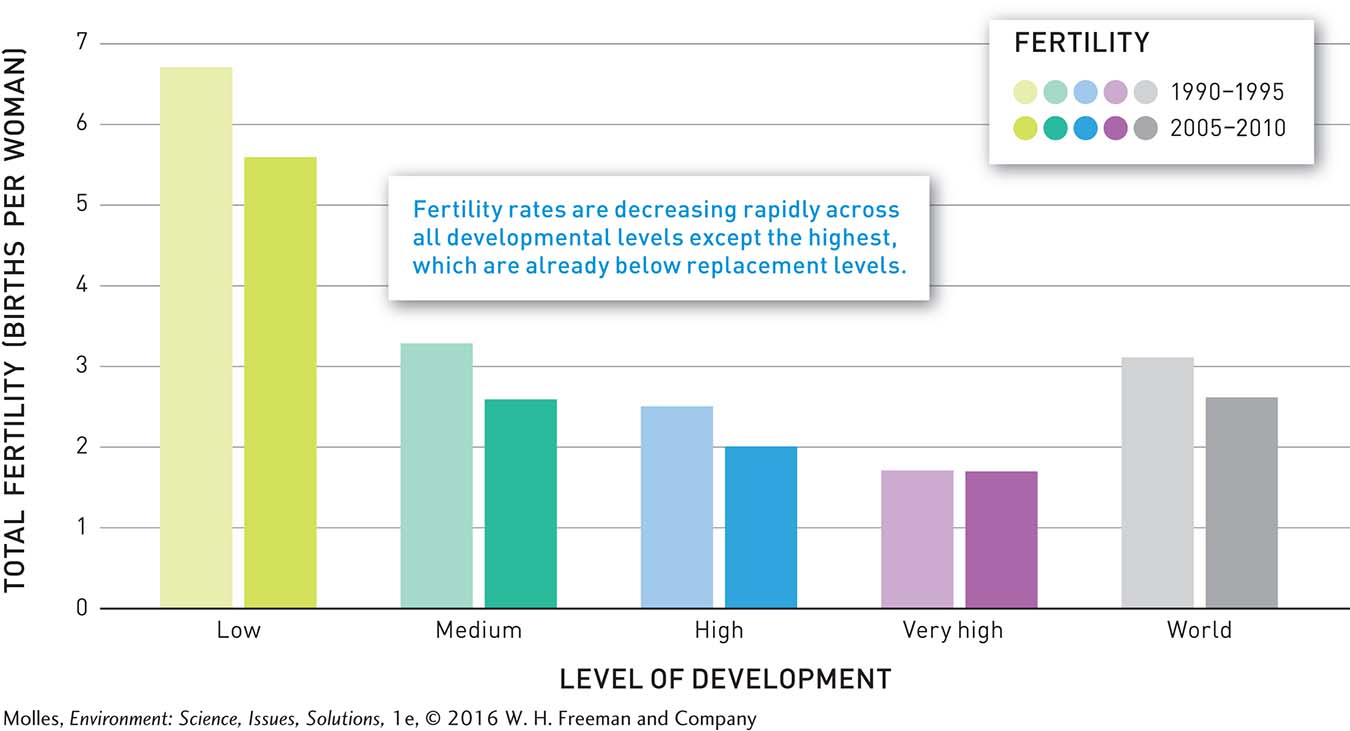

As in India and China, total fertility rates are falling rapidly the world over due to a “reproductive revolution” caused by national policies, education, and contraception. As shown in Figure 5.26, between 1990 and 2010, total fertility rates fell significantly in countries at virtually all levels of development. The richest countries showed no change, in part, because fertility rates were already at 1.7 births per woman, well below replacement levels. At the global level, these declines translate into a decrease in fertility from 3.1 to 2.6 births in just two decades. Demographers predict that total fertility for the world will decline to the replacement level of 2.1 sometime before 2050.

What are some of the serious social and economic costs of having a population with fewer young than older members? What are some ways to reduce those costs without creating other problems?

Think About It

When the least developed nations wish to provide family-

planning services and contraceptives for their people but lack the funds to do so, should the most developed countries provide the necessary funding? At what point do international campaigns for population control interfere with the rights of nations to manage their own internal affairs?