6.6 Managing water for human use threatens aquatic biodiversity

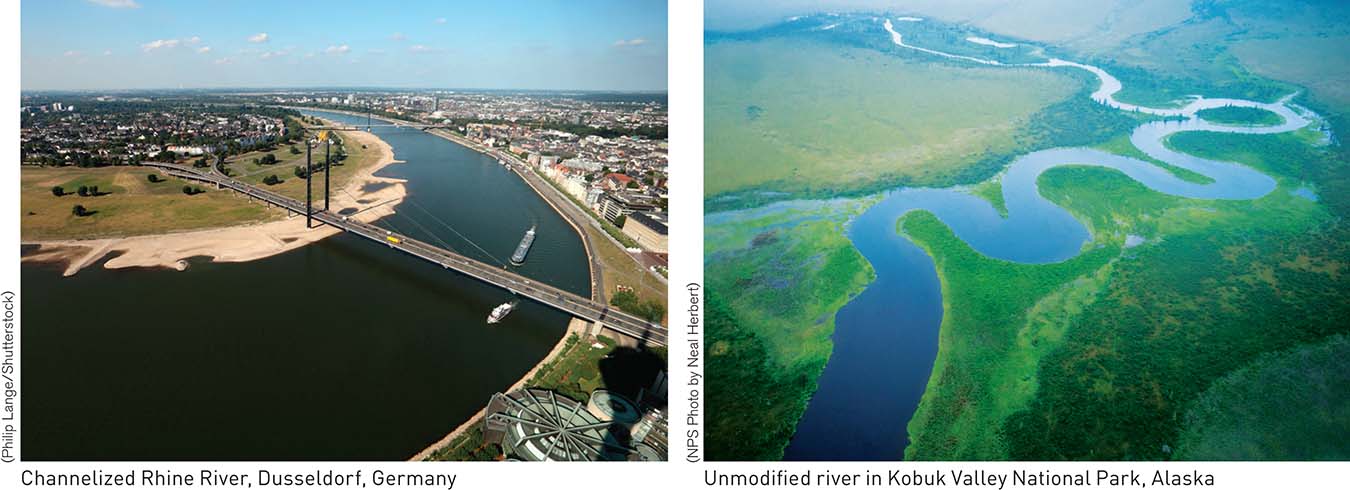

Building dams for irrigation, draining wetlands for agriculture, or filling a marsh to build an airport are obvious examples of how humans destroy aquatic ecosystems. Invasive species, such as Asian carp (see Figure 3.22, page 79), can compete with and displace native fish species. Straightening river channels to make them better suited for shipping has also reduced the diversity of aquatic habitats along approximately half a million kilometers of river channels around the world.

Dams and Aquatic Biodiversity

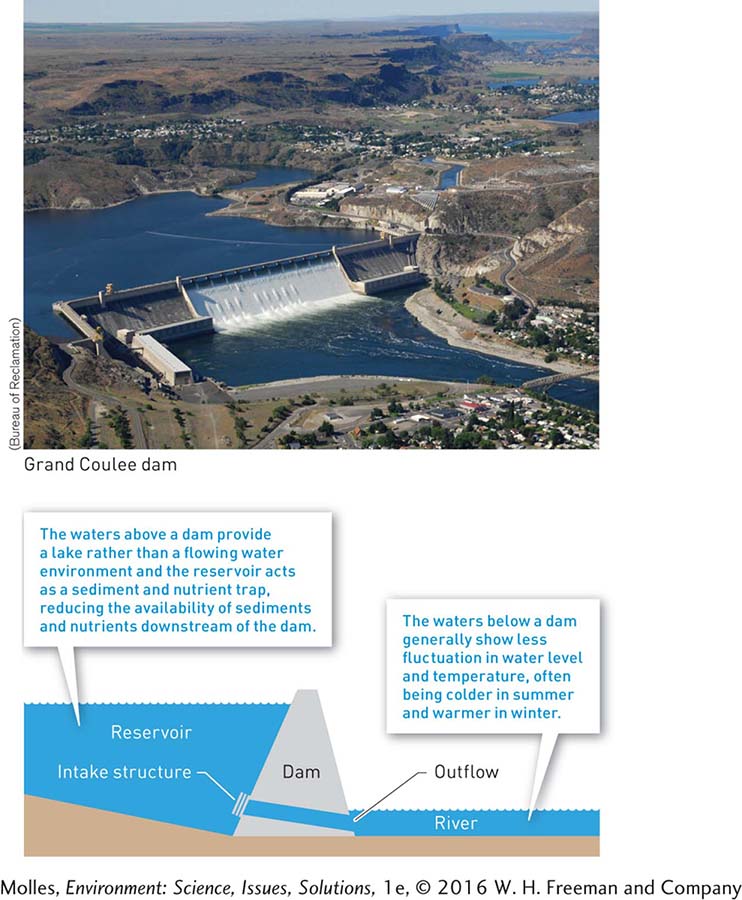

To manage water supplies, we have built dams on rivers the world over. While dams help solve problems of variable water supplies and can protect against flood damage, they change the environment in many ways and often threaten biodiversity (Figure 6.17). During periods of drought, dammed rivers may dry up entirely. Even where water continues to flow below a dam, the river environment is never the same. Because reservoirs trap sediments and nutrients, they reduce the amount available to the river below the reservoir.

Dams also alter the temperature of rivers. When frigid water is released from gates at the bottom of a reservoir during the summer, the river temperature downstream can drop by several degrees. Many species require floods or low flows to complete their life cycles and are thus harmed when dams prevent those conditions. River ecologists estimate that dams and water diversions have altered more than 75% of the 139 largest rivers in the Northern Hemisphere. Within the United States alone, there are more than 75,000 dams.

Dams usually prevent fish from moving up and down the length of the river, which is especially harmful to migratory fish such as salmon (see Chapter 8). Nonmigratory species might also decline as a result of dam building. For instance, many of the native fish populations of the Colorado River, including the Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius), declined as the river was modified for water management. The Colorado pikeminnow was more monster than minnow, weighing up to 80 pounds and reaching lengths of 5 feet. This fish had evolved into the top predator in the Colorado River over a period of millions of years but was brought to the brink of extinction in less than a century by dam building. The dams impact the pikeminnow in several ways: They create the lake-

The pikeminnow is just one example of how humans have harmed aquatic organisms through their activities (Figure 6.18). Approximately 20% of the freshwater fishes of the world are threatened with extinction or are already extinct. Within the United States, nearly half of the federally listed endangered vertebrate and invertebrate animals are freshwater species.

Water Management and Wetland Biodiversity

oxbow lake A crescent-

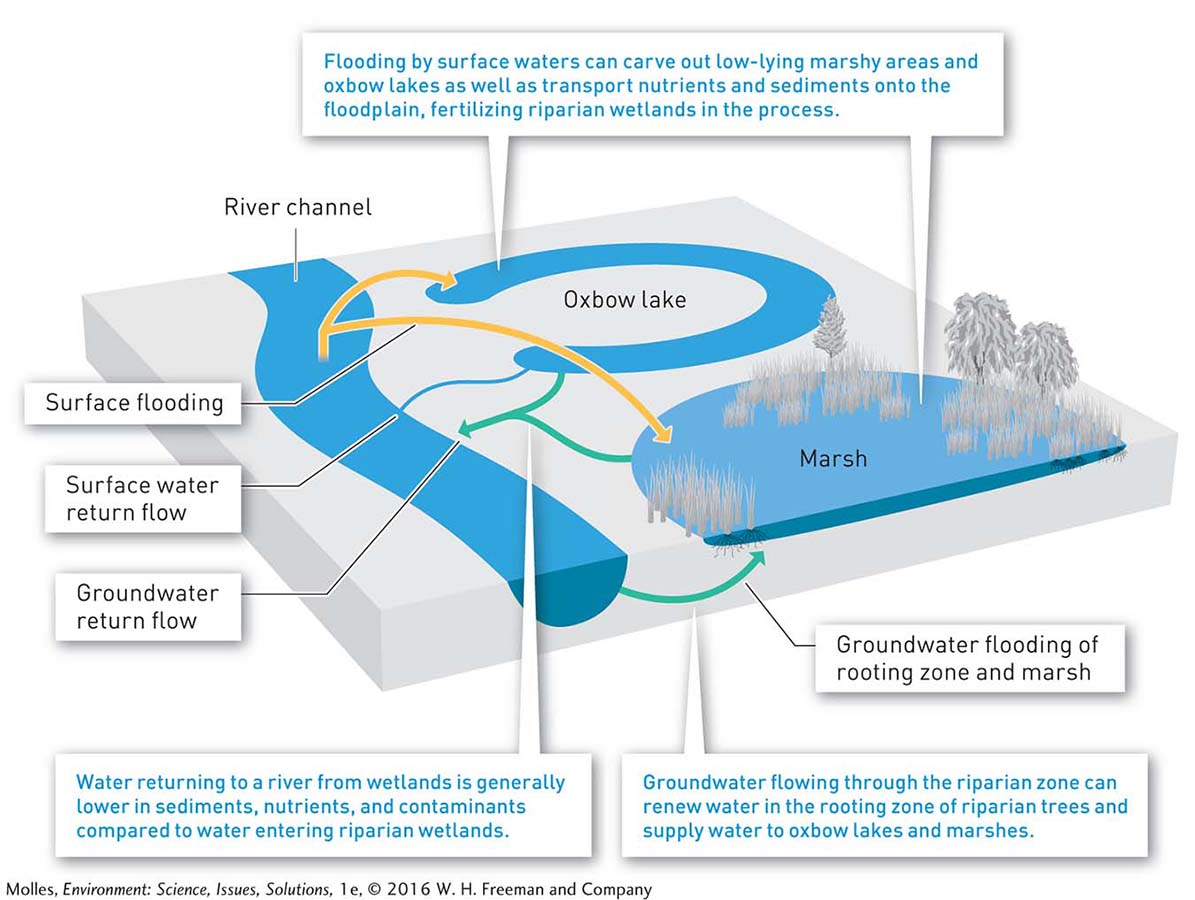

When rivers flood their banks, water spills out onto the floodplain. While floods may harm crops and destroy houses and other structures on a floodplain, they are essential to the health of wetlands. Floods disperse valuable nutrients into the soils of the floodplain and rearrange the landscape; for example, they isolate old river channels, forming riverside habitats called oxbow lakes. Likewise, wetland ecosystems act as natural water purifiers capable of removing or reducing the concentrations of various contaminants (Figure 6.19).

channelize To engineer a change to the natural form of a stream or river, including straightening, deepening, or widening the channel.

Building dams and regulating river flow directly harm these wetlands by preventing natural floods. A common manipulation of rivers is to channelize them, an engineered change to the natural form of a stream or river, including straightening, deepening, or widening the channel. While a channelized river may make navigation easier, it disrupts the natural connection between a river and its floodplain (Figure 6.20). In addition, the sediment-

riparian The transition zone between a river or stream and the terrestrial environment, generally inhabited by a biological community distinctive from adjacent aquatic and upland communities. Riparian zones naturally flood periodically and usually have shallow water tables.

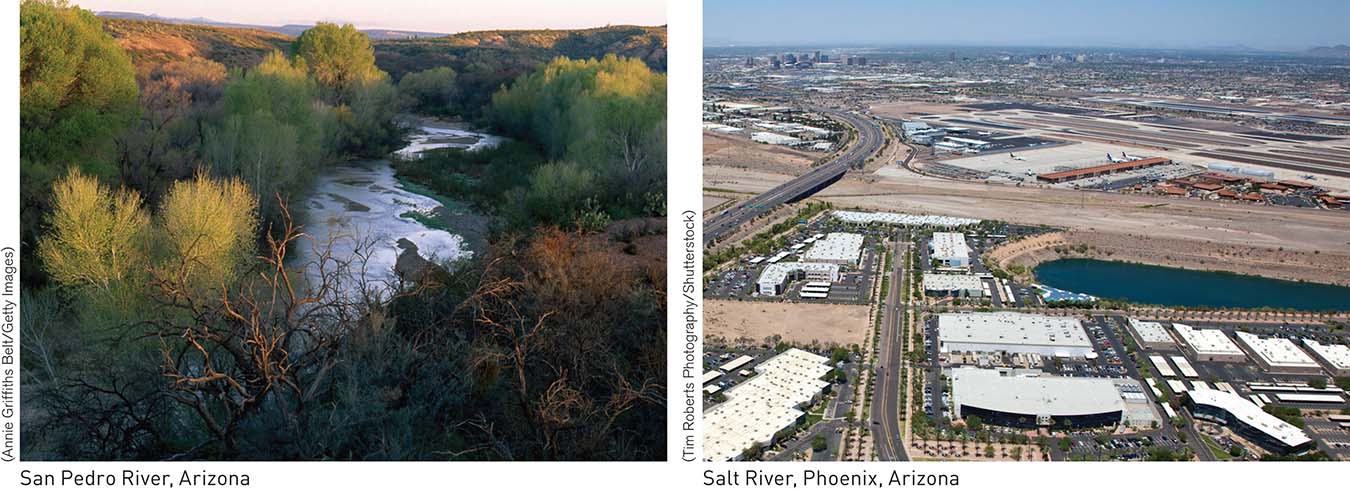

Riparian areas, which form the transition zone between a river or stream and the terrestrial environment, have been heavily impacted by dam building and flow regulation. These areas usually have shallow water tables and depend on regular floods in order to support a biological community distinctive from adjacent aquatic and upland communities. Connections between rivers and wetlands are especially critical in arid climates, where riparian wetlands support unusually high levels of biodiversity, compared with the surrounding landscape. However, dams and channels in those areas have reduced the frequency and intensity of flooding. Where the demand for water to supply municipalities and agriculture has been especially great, water diversions have commonly dried river channels entirely (Figure 6.21). Concerns about such impacts on biodiversity and productivity have stimulated efforts at riparian and wetland restoration (see Solutions, page 181).

Many wetlands were drained to reduce the incidence of mosquito-

Think About It

Should the value of ecosystem services lost as a consequence of water management be considered as part of the price of water delivered to consumers? Explain.

Municipalities and landowners generally have a legal right to use a certain amount of water per year. Should there be legislation limiting human water use and requiring minimum river flows to protect endangered species?

In the event of dwindling water supplies, what type of use should be given higher priority and which should be given lower priority? Why?

6.3–6.6 Issues: Summary

Approximately 2.6 billion people around the world lack access to enough water to meet their basic needs. Continued population growth, coupled with natural variation in water supplies, will intensify the potential for conflict among water users, especially in arid regions. Only about one-

Alteration of freshwater environments around the world threatens many aquatic species, ranging from mollusks to fish. Dams, built to store water and control floods, change river ecosystems in many ways, including blocking the passage of migrating fish, altering historical patterns of flow, changing water temperatures, and reducing the availability of nutrients and sediments in river sections below dams. By reducing flooding, dams also decrease the connection between rivers and riverside wetlands and forests, which make particularly valuable contributions to biodiversity and primary production in arid and semi-