7.10–7.13 Solutions

Providing adequate nutrition to human populations and sustaining the production of food and timber to our growing communities over the long term are perhaps the most fundamental issues we have dealt with since our origin as a species. In this section, we examine some successes in increasing agricultural production and sustaining the production of terrestrial ecosystems, while protecting the integrity of ecosystems and biodiversity.

7.10 Investing in local farmers, while increasing genetic and crop diversity, may be a sustainable approach to feeding our growing population

The most sustainable approach to combating malnutrition and undernourishment around the world may be to help local farmers produce adequate quantities of nutritious food. It may also be the most cost-

Supporting Local Farmers

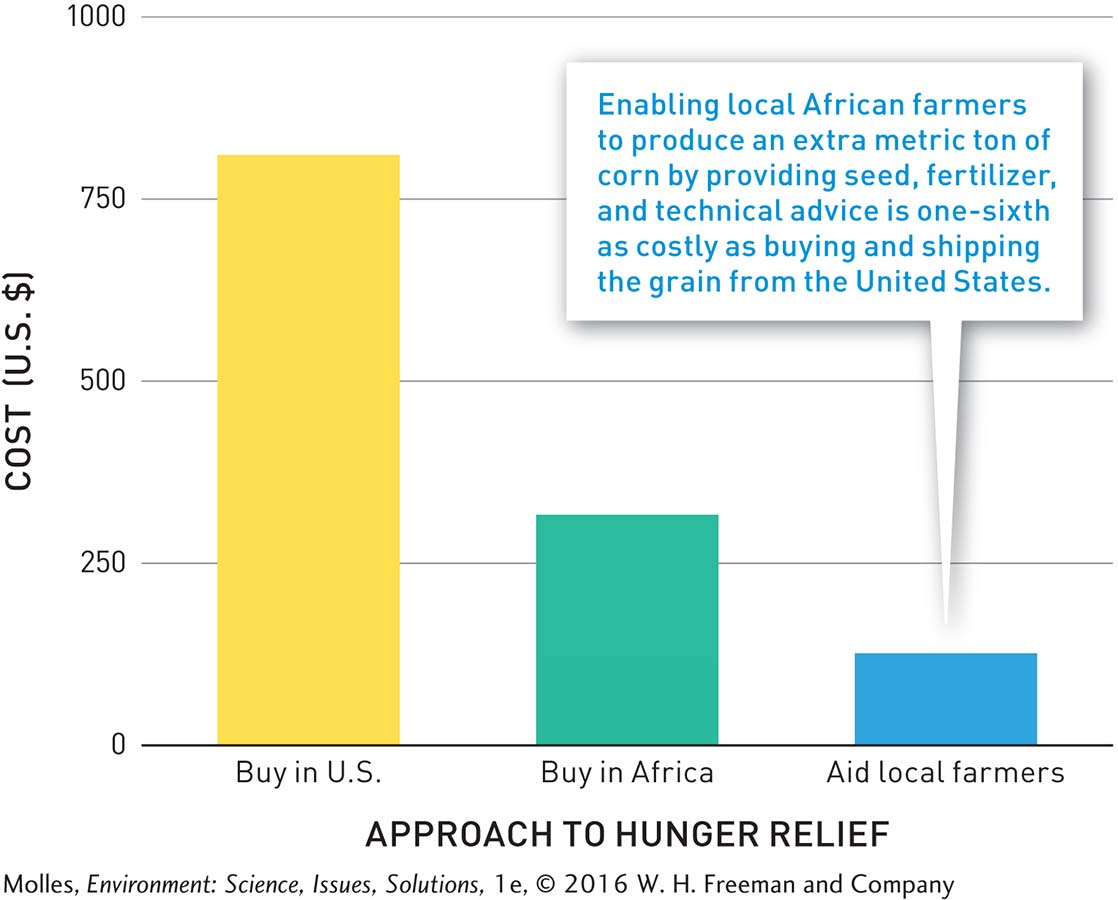

In a 2009 article in the journal Nature, Pedro Sanchez, Director of Tropical Agriculture at Columbia University, compared the cost of three approaches to providing hunger relief in Africa. His comparison was based on the cost of delivering 1 metric ton of corn. As shown in Figure 7.32, buying and shipping corn from the United States is the most expensive way to deliver food aid.

Buying corn in Africa and distributing it locally cost less than half what it would take to buy and ship from the United States. However, providing local farmers with the fertilizer, seed, and technical assistance to produce an extra ton of corn is only one-

Crop Diversity for Productivity and Sustainability

Intensive agriculture, which was at the center of the Green Revolution, focused on producing food through large-

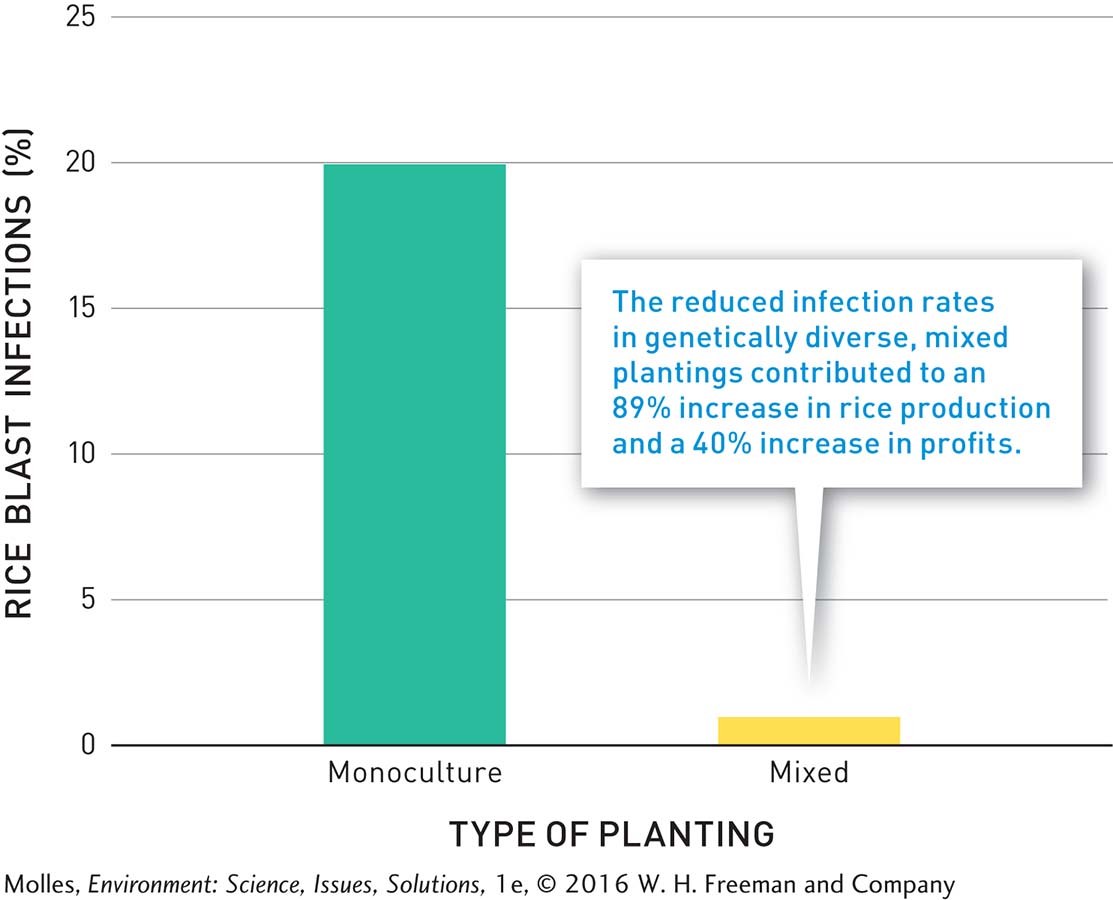

Genetic diversity, one of the basic components of biodiversity (see Chapter 3, page 62), has proved a powerful tool for increasing rice yields in China, echoing the results of Tilman’s study, covered earlier in the chapter. Youyong Zhu of Kunming University in southwestern China led a team that investigated the potential for reducing the loss of rice production—

What are the potential costs of planting two or more varieties of a crop in close proximity?

The reduction in rice blast infection in these mixed fields was dramatic. The rate of infection in monocultures of the sticky rice was 20% compared with 1% in the mixed plantings (Figure 7.33). The increased distance between susceptible plants and modification of temperatures, humidity, and light were likely responsible for creating conditions less favorable for the pathogen than those in monocultures of sticky rice. Furthermore, it was not necessary to spray fungicidal chemicals to control rice blast in the mixed field, thus saving money. Reducing rice blast infections resulted in an 89% increase in yield of the valuable sticky rice varieties and a 40% higher gross economic return per hectare.

Rice farmers across China took notice. In Yunnan and 10 other Chinese provinces, the area in mixed plantings increased to 1.57 million hectares between 2000 and 2004. Across this vast area, rice yields increased by an average of 675 kilograms (1,488 pounds) per hectare, and $259 million were gained either through increased income or reduced costs. Agricultural scientists have demonstrated similar boosts in yield resulting from higher genetic diversity in other crops.

Some of the benefits of biodiversity to crop production can be realized by growing different crops sequentially on the same field generally over a period of three to five years, a practice called crop rotation. For example, a farmer might plant corn in one field, and then plant a different crop in that same field the next year, and the year after. The benefits of crop rotation include increased yields, and lower insect and disease infestations. Crop rotation can also improve soil aeration when deep-

intercropping Growing two or more crops in the same field.

Biodiversity can be incorporated into agricultural systems by growing two or more crops in the same field, a technique called intercropping. Intercropping has been practiced for centuries. For example, Native Americans developed a traditional intercropping system in which they grew corn, beans, and squash together, a combination of crops commonly referred to as “the three sisters” (Figure 7.34).

In this system, beans enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen, the corn provides a surface for attachment by the climbing bean plants, and the squash shades the soil, thereby reducing temperature fluctuations and water loss. The three crops also provide complementary sources of nutrition: Combining the amino acids of beans, corn delivers all the essential amino acids required by humans, while squash provides a rich source of vitamin A.

Modern researchers and farmers are rediscovering the benefits of intercropping. Faced with the daunting task of feeding its 1.3 billion people on limited agricultural lands, China has been investing heavily in agricultural research. The ultimate prize in such research would be the development of low-

Think About It

Aside from monetary costs, what is the difference in relieving hunger by buying and shipping food from developed countries versus helping local farmers improve their farm production?

What are the benefits of crop genetic diversity? Besides rice, do you know of any other crops threatened by a lack of diversity? Cite examples.

Why does intercropping or crop rotation generally give a bigger boost to crop production when one of the crops involved is a legume, such as soybeans or alfalfa?