7.8 Intensive agriculture can cause pollution and promote pesticide resistance

pesticide Generally a chemical substance used to kill destructive organisms, including insects (insecticide), fungi (fungicide), weeds (herbicide), and rodents (rodenticide).

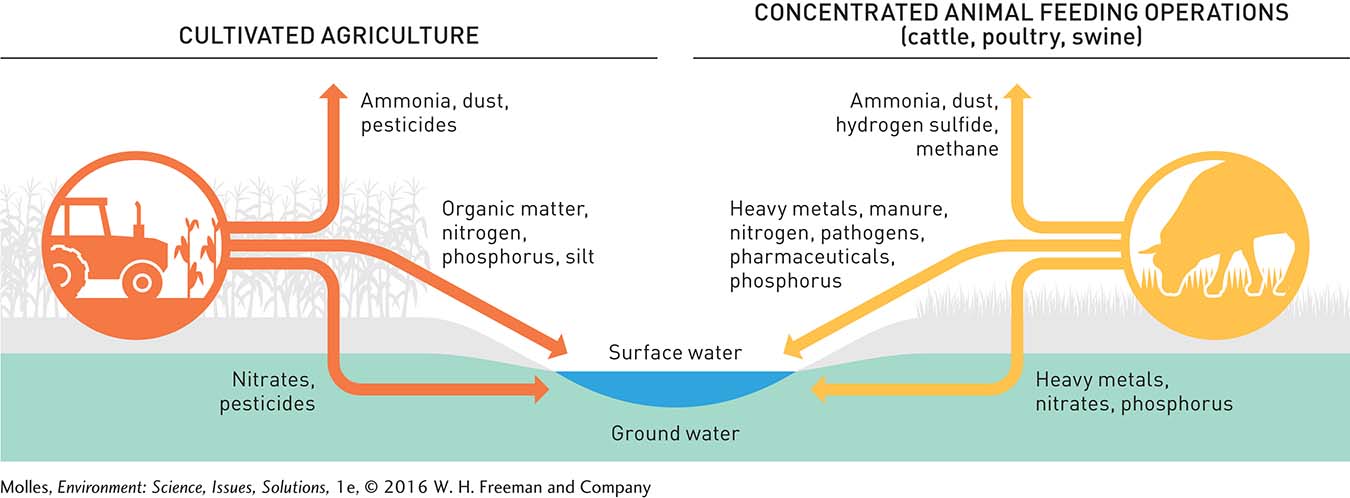

Many approaches to improving agricultural production, such as the addition of fertilizers and pesticides, can cause pollution (Figure 7.24). In Chapter 13, we examine the impacts of agricultural pollution, particularly pollution resulting from concentrated animal feeding operations and intensive agriculture, on aquatic ecosystems and populations; in Chapter 11, we examine them from environmental risk and human health perspectives. Here, we focus our attention on pollution by chemical pesticides and the evolution of pesticide-

Pest Control and Pollution

The leaf beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata is about the size of a pencil eraser and has a bright orange head with ten brown and yellow stripes along its back. It was largely unknown until 1859, when an outbreak occurred on potato fields near Omaha, Nebraska. As the leaf beetle population expanded across the United States and Canada to Europe and Asia, decimating crops in its wake, it earned its common name, the Colorado potato beetle. Since then, hundreds of chemicals have been tested and developed to fight this beetle, making it a key focus during the development of the modern pesticide industry.

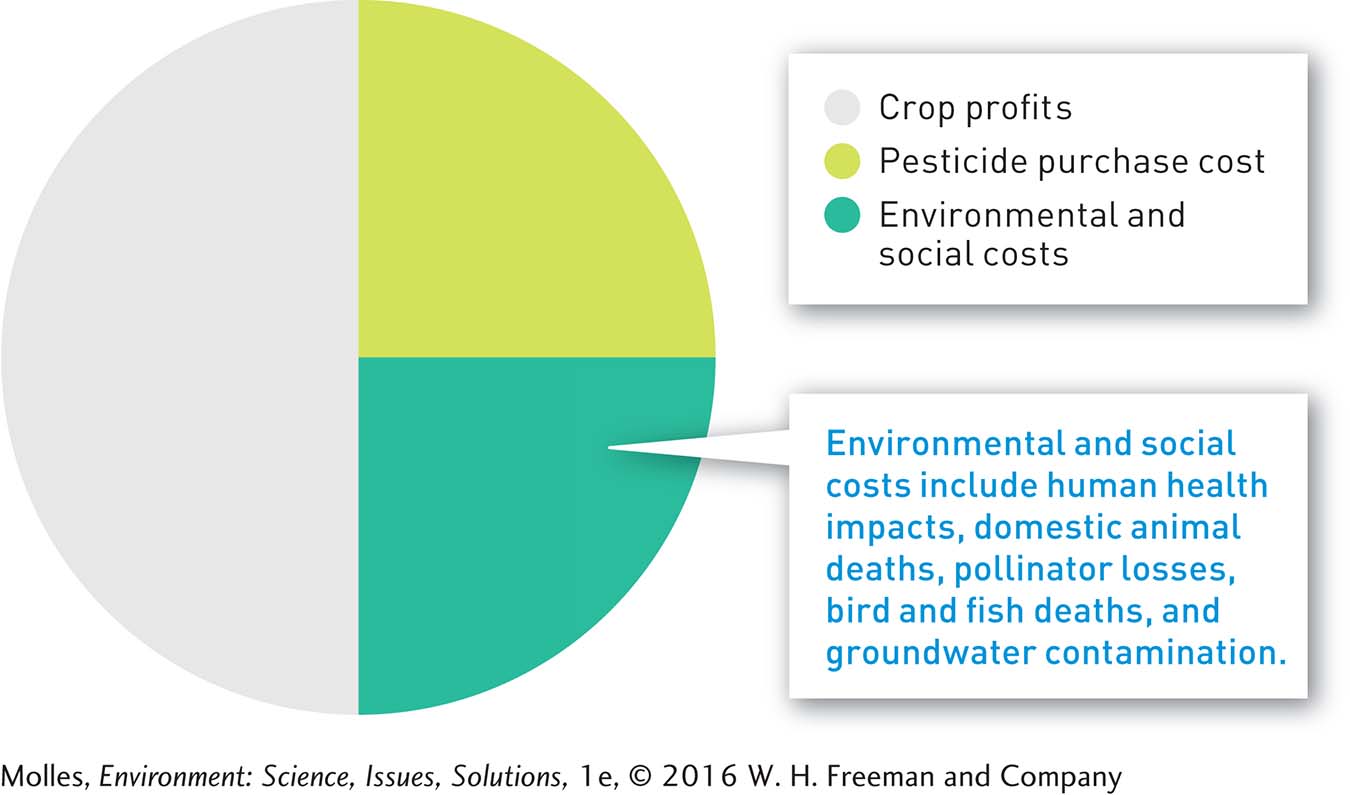

Today, U.S. farmers apply 500 million kilograms (1.1 billion pounds) of pesticides annually to protect crops valued at about $40 billion from pests, pathogens, and plant competitors. In spite of the application of massive quantities of pesticides, insects, pathogens, and weeds still reduce potential annual crop production in the United States by nearly 40% (Figure 7.25).

The benefits of pesticides in crop protection are accompanied by various costs, however. The annual price tag for pesticides in the early 2000s was approximately $10 billion. Additional environmental and social costs resulting from pesticide use totaled $10 billion, including the costs associated with the poisonings of domestic animals, wild birds, fish, and honeybees and other pollinators (Figure 7.26). Around the world, pesticide poisoning results in the hospitalization of approximately 3 million people and more than 200,000 deaths each year, the majority of which occur in developing countries. The estimated annual cost of human pesticide poisoning in the United States alone is over $1 billion.

Pesticide Resistance and Loss of Insect Predators

pesticide resistance

An evolved tolerance to a pesticide by a pest population as a result of repeated exposure to a pesticide, ultimately rendering the chemical ineffective.

Pesticides have not proved to be a silver bullet in saving crops from insect damage. In 1952 farmers noticed that the widely used pesticide dichloro-

natural enemies Predators and pathogens that attack herbivorous insects and other pest organisms.

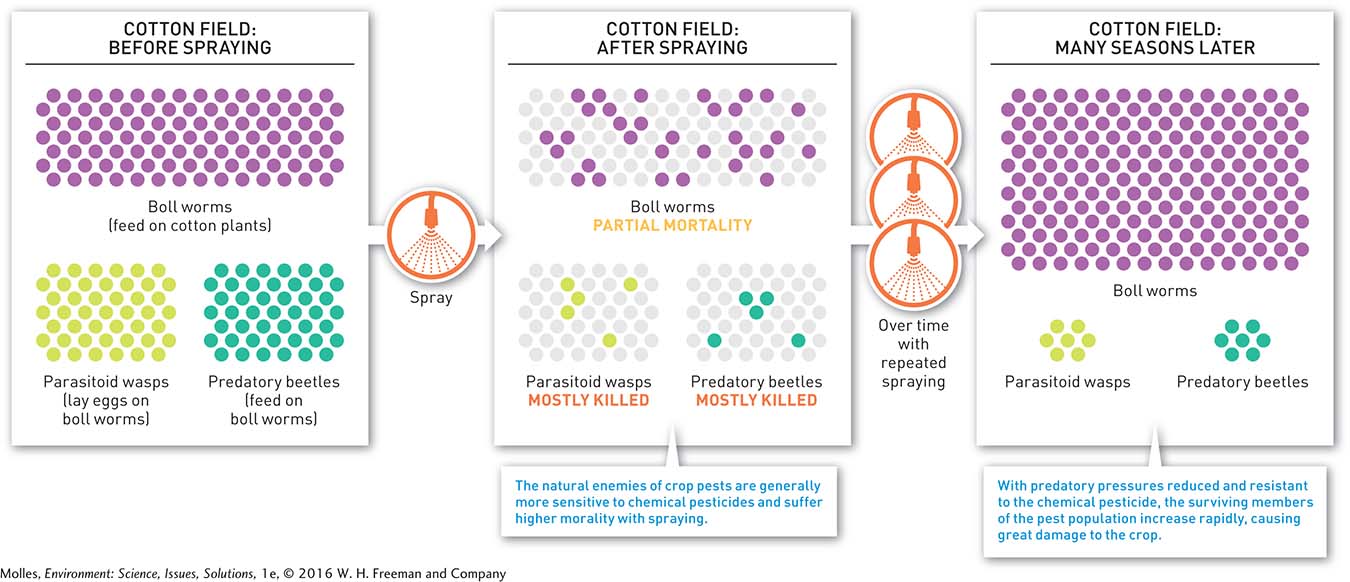

For instance, growing potatoes or other crops in extensive monocultures creates an attractive target for pests and pathogens. A large crop field is an easy target for insect pests to find, colonize, and multiply their population. Also, the physical homogeneity of monocultures reduces the amount of habitat available to support the natural enemies, the predators and pathogens that attack herbivorous insects and other pest organisms. Then, as we apply pesticides, we kill not only pests, but also the spiders and predaceous insects that help control them.

In a final irony, applying chemical pesticides exerts strong natural selection for the evolution of resistance to those same pesticides—

Think About It

According to Figure 7.26, how much of the value of crops protected by pesticides is profit, once the costs of pesticides have been paid?

How might research on alternatives to chemical pesticides be affected if farmers and the chemical industry paid all costs, including environmental and social costs, of pesticide use?

What role does the intensity of pesticide application likely play in the evolution of pesticide resistance among agricultural pest populations?