8.4–8.6 Issues

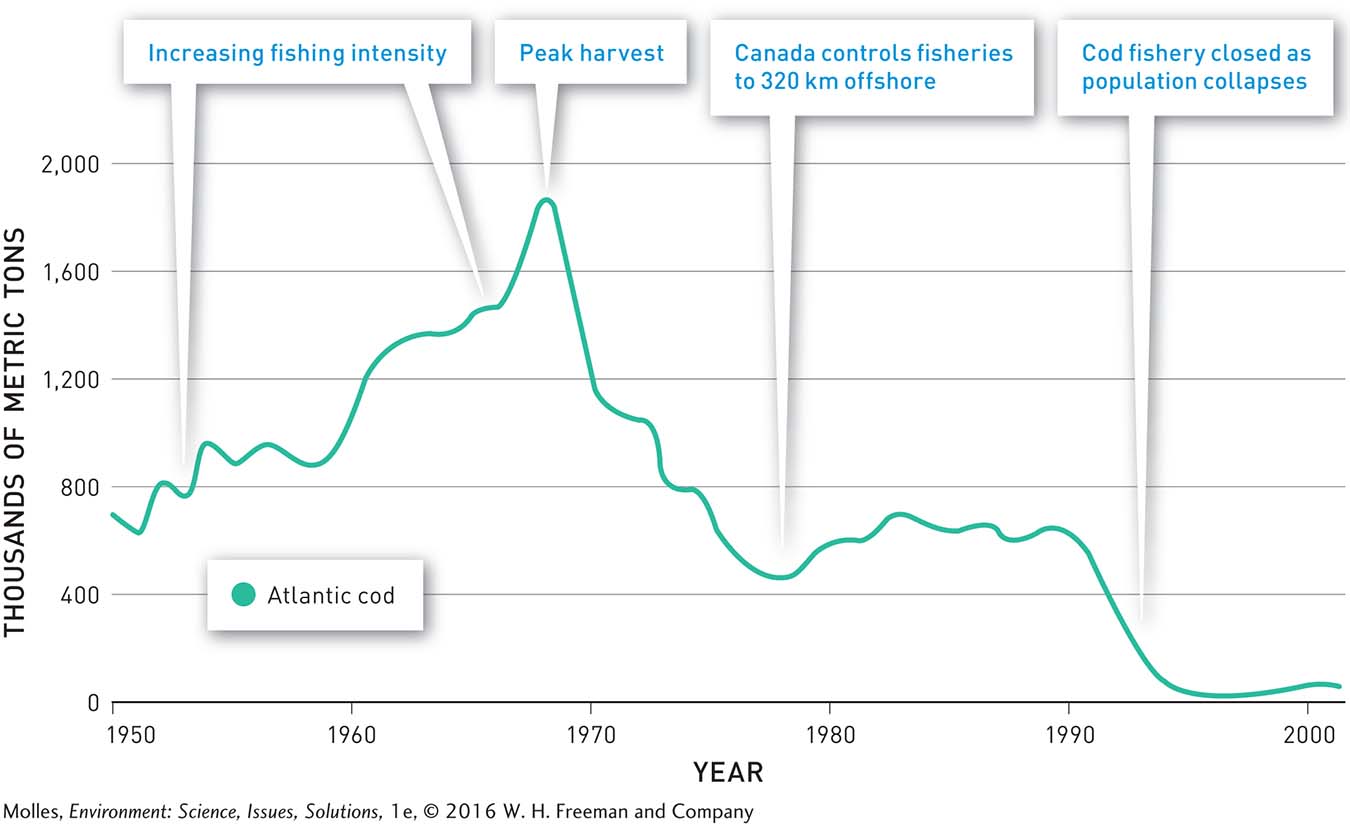

Peruvian anchovy populations crashed in the 1970s. Blue walleye went extinct in the Great Lakes in the 1980s. Atlantic cod collapsed in the 1990s. The dire state of all these commercial stocks demonstrated that we have the technical capacity to deplete what was once thought to be inexhaustible. Fish stocks around the world have been harmed not only by overharvesting, but by pollution, dams, and the changing climate.

8.4 Tragedy of the Commons: Intensive harvesting has resulted in overexploitation of many commercially important marine populations

Once humans were able to navigate the open waters of the entire planet and developed techniques for catching and processing massive harvests at sea, they soon had the means to decimate entire populations of marine organisms.

Depletion of Whale Populations

Humans have been hunting whales for more than 3,000 years—

For many years, the blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus, and the fin whale, B. physalus, remained beyond the reach of early whaling technology because they were too fast, too strong, and sank when killed. This changed with the invention of the harpoon gun, explosive harpoons, and steam-

The history of commercial whaling is a good example of how the Tragedy of the Commons leads to overexploitation of resources (see Chapter 2, page 49). During the time of peak commercial whaling, no international agreements or regulations limited harvest. Because whales mostly live in areas away from international borders, whalers were free to harvest as many whales as they could sell to meet commercial demand. Ultimately, the collapse of many whale populations and rising popular awareness of the overharvest of whales sparked international agreements to ban whaling in 1982. Those bans are still in place today, with a few notable and controversial exceptions.

An Ecosystem Upturned: Atlantic Cod

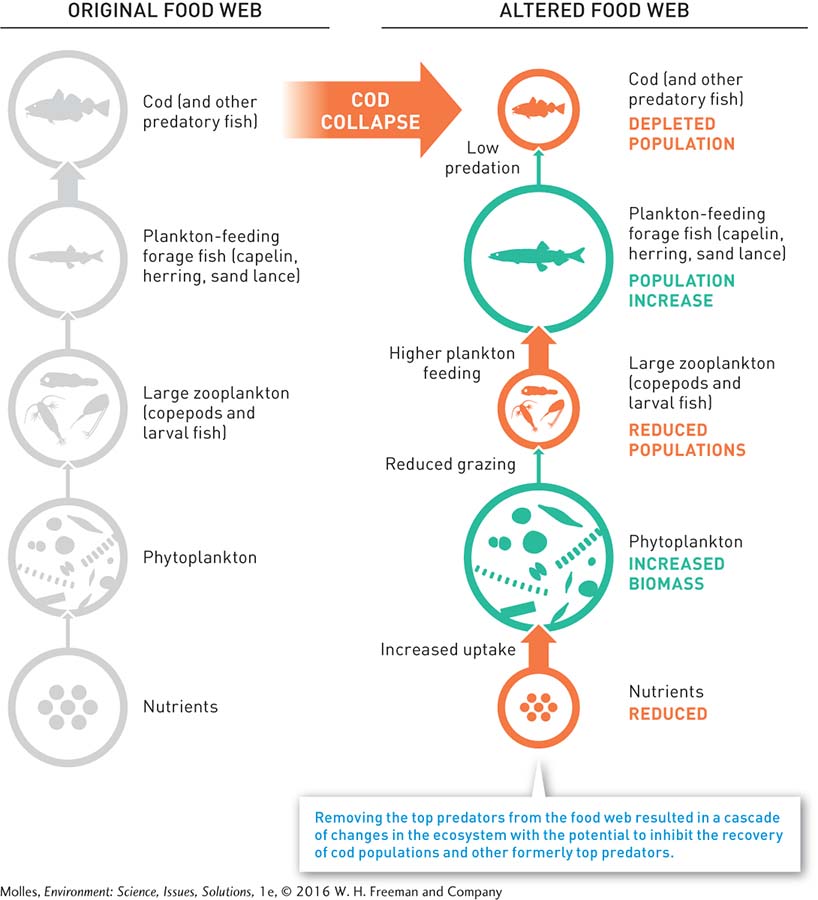

As the cod fishery in the northwest Atlantic collapsed (Figure 8.11), marine scientists discovered that other species, such as hake, haddock, and pollock, were also in trouble. All these fish were historically dominant predators, and their absence due to overharvest transformed the ocean ecosystem in many ways (Figure 8.12). Bottom-

Fisheries Collapse: A Global Problem

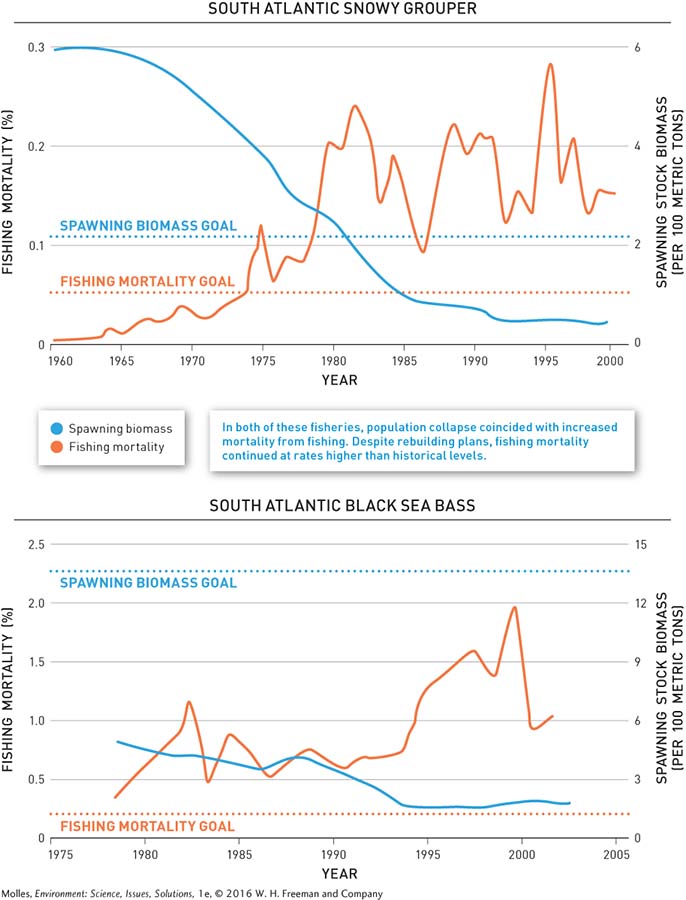

Similar to the history of whaling, the collapse of the cod fishery off Canada and New England is a sobering example of a Tragedy of the Commons (see page 49). But many other exploited fish populations have also collapsed, including the sardine fishery off California and the blue tuna fishery in the Atlantic. Recent estimates indicate that more than 25% of commercially important fish stocks have suffered declines in numbers sufficient to be classified as a “collapse” in the fishery. Figure 8.13 shows the patterns of population decline under exploitation for two of these fish stocks: the South Atlantic snowy grouper and the South Atlantic black sea bass.

One factor in these declines has been the over-

Remaining Uncertainty

While our understanding of the status and biology of commercially important fish populations grows rapidly, significant gaps in our understanding remain. In 2013, of the 230 stocks of commercially important marine fish under U.S. jurisdiction, the status of 23% was uncertain or undetermined. Meanwhile, significant percentages of commercially important fish stocks off northwest Europe and New Zealand also had uncertain or undetermined status. Clearly, increased information on the status of these stocks would help with their management, especially in regard to regulating fishing pressure.

Think About It

How did technological development influence the overharvesting of whale and fish populations?

In what ways does the collapse of the commercial whaling industry or the northwest Atlantic cod fishery represent a Tragedy of the Commons?