8.5 Dams and river regulation have decimated migratory fish populations

Building dams on rivers can stabilize water supply and protect people and infrastructure from flooding. However, dam construction can also displace human populations dependent on rich floodplain resources, forcing them to make a living in less productive environments. Dam construction has many benefits and costs, but here we focus on how river modification by dams threatens populations of commercially important migratory fish, especially salmon.

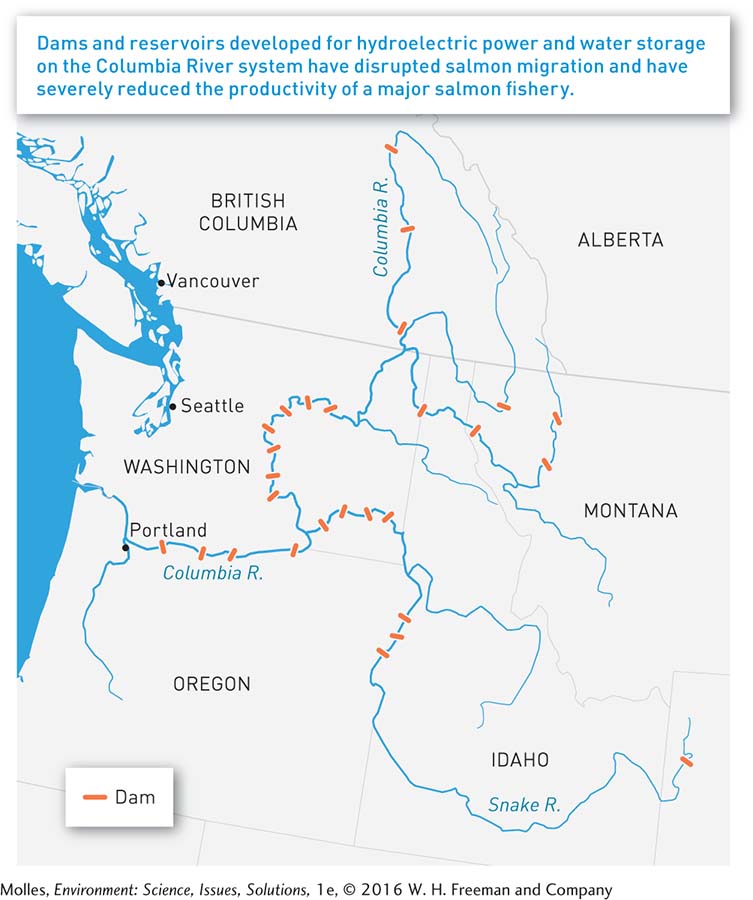

The Columbia River

How do you think we should weigh the relative environmental costs against the economic benefits of dams?

In the early 19th century, some 8 to 10 million adult salmon would swim up the Columbia River every year to spawn in the river and its tributaries. But the construction of over 100 large hydroelectric dams converted the once large, free-

The Klamath River

Another important salmon river, the Klamath, flows through northwest California and southeast Oregon (Figure 8.15). It was once the third most productive salmon river of the U.S. West Coast, with half a million fish returning to spawn each year. However, Copco 1, a hydroelectric dam built in 1918, made most of the upper Klamath River basin inaccessible to salmon and other migratory fish. Three additional hydroelectric dams, built on the Klamath from 1925 to 1962, prevented migratory salmon from reaching approximately 970 kilometers (600 miles) of spawning streams in the upper Klamath River system, reducing the potential of the river system to produce salmon.

These Klamath River dams have also had indirect impacts on salmon populations. Water diversions for agriculture have reduced flows in the river, and drainage from irrigated agricultural fields has introduced excess nutrients and organic contaminants such as pesticides into the river. Nutrients coming from upstream agricultural areas foster blooms of algae in the reservoirs and below them. Decomposing algae trigger oxygen depletion, which stresses salmon physiologically and leads to the spread of salmon diseases. In 2002, for instance, pathogens killed at least 33,000 adult salmon in the Klamath (Figure 8.16). In addition, water in the reservoirs behind the dams warms to temperatures unsuitable for salmon, which are a cold-

How are the collapse of the Klamath River salmon and the collapse of the cod fishery similar? How are they different?

As a result of the combined effects of reduced spawning area, low water quality, and the ravages of pathogens, salmon and steelhead runs in the Klamath River have been reduced by approximately 90%. The decline in these stocks led to the closure of 1,000 kilometers (700 miles) of the West Coast of the United States to commercial salmon fishing from 2008 to 2011.

Mekong River Dam

The Mekong River is one of the world’s longest rivers, flowing 2,700 miles from the Tibetan plateau through Southeast Asia and into the South China Sea. Fish from these waters provide much-

Think About It

Should China consider how dam construction in that country will affect river productivity in other downstream countries? Explain why or why not.

Although dams harm migratory fish populations, some nonmigratory species of lake fish benefit from dams. Is this a balanced tradeoff?