8.7–8.10 Solutions

Is it possible to reverse the damage caused by decades of overfishing? In its 2013 Status of Stocks report to the U.S. Congress, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that seven stocks had been removed from the overfishing list and four stocks were removed from the overfished list. On top of that, two stocks—

8.7 Saving global fish stocks requires careful management and strong incentives

Recognizing the impact of unchecked fisheries harvest on wild populations, regulators have experimented with a variety of methods for restoring and managing populations. Establishing sustainable fisheries depends on having sound fisheries science, rational regulations, and appropriate enforcement for violators.

Moratorium on Whaling

The most dramatic measure used to regulate a fishery is a total shutdown. In 1982 the International Whaling Commission declared a “pause” in commercial whaling, although some whales had been protected for much longer. For example, the gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus, has been protected from commercial whaling since 1946. How have whale populations responded to this global protection? Many populations are growing very rapidly, including the right whales of the southern oceans, whose population has been increasing at rates of 7% to 8% annually (Figure 8.21).

Some populations of whales have even recovered to numbers not seen since before commercial whaling. For example, the gray whale population in the eastern Pacific Ocean has rebounded to about 20,000 individuals, which is the estimated historical population size; these whales have been removed from the endangered species list. Scientists also estimate that the humpback whales in the western Atlantic have also recovered to pre-

This success has been accompanied by criticism of whaling nations such as Iceland and Japan. Throughout the moratorium, these countries have continued to engage in whaling under the auspices of “scientific” data collection, which has angered animal rights activists and conservationists and has revealed the limits of international treaties. Commercial whaling in Iceland officially resumed in 2006 with the harvest of 7 fin whales and 1 minke whale. Currently, the country sets a harvest quota of 40 minke whales each year. Although scientists believe that sustainable harvests are feasible, many people would like to keep the moratorium in place for ethical reasons because whales are such charismatic and intelligent creatures.

Fishing Restrictions

How does the white seabass fishery situation demonstrate why bycatch is an important consideration in sustainable fishery management?

Regulators have a variety of other, less severe methods to ensure sustainable fishing harvests. For instance, lobstermen in Maine can harvest only lobsters with a body shell between 8.3 and 12.7 centimeters (3.25 and 5 inches) long. They are also required to mark and throw back any female lobsters with eggs. Regulators may also limit the length of the fishing season to avoid the breeding season, as well as the number of days fishers can spend at sea. In the United States, fishers who break these rules can be liable for tens of thousands of dollars in fines or even the loss of their commercial fishing license.

One of the most important ways in which regulators restrict fishing and reduce bycatch is by limiting the type of gear that can be used, including the size of the mesh in nets or the type of nets. Bycatch often kills or injures many nontarget organisms that are caught in fishing gear, and the loss of those organisms affects aquatic food webs. Fishers in the Southern California Bight, an area off the coast of southern California that includes the Channel Islands, used to set gillnets vertically in the water to catch white seabass. However, these nets also captured many other kinds of fish, leading to severe population declines in nontarget species that were important components of the marine food web. After the state of California banned the nets, the populations of four large predatory fish species—

What indirect positive effects on management may result from involving local communities in scientific studies?

One of the most effective ways to encourage fishers to follow management guidelines and adhere to management goals is to involve them in the gathering of scientific information and in the fishery management decision-

Catch Shares

individual transferable quota (ITQ) (catch shares) A guaranteed right to a certain portion (quota) of the catch in a fishery or exclusive rights to certain fishing grounds; may also be granted to a fisheries cooperative or community.

Another approach to managing fisheries is to replace the competitive “race-

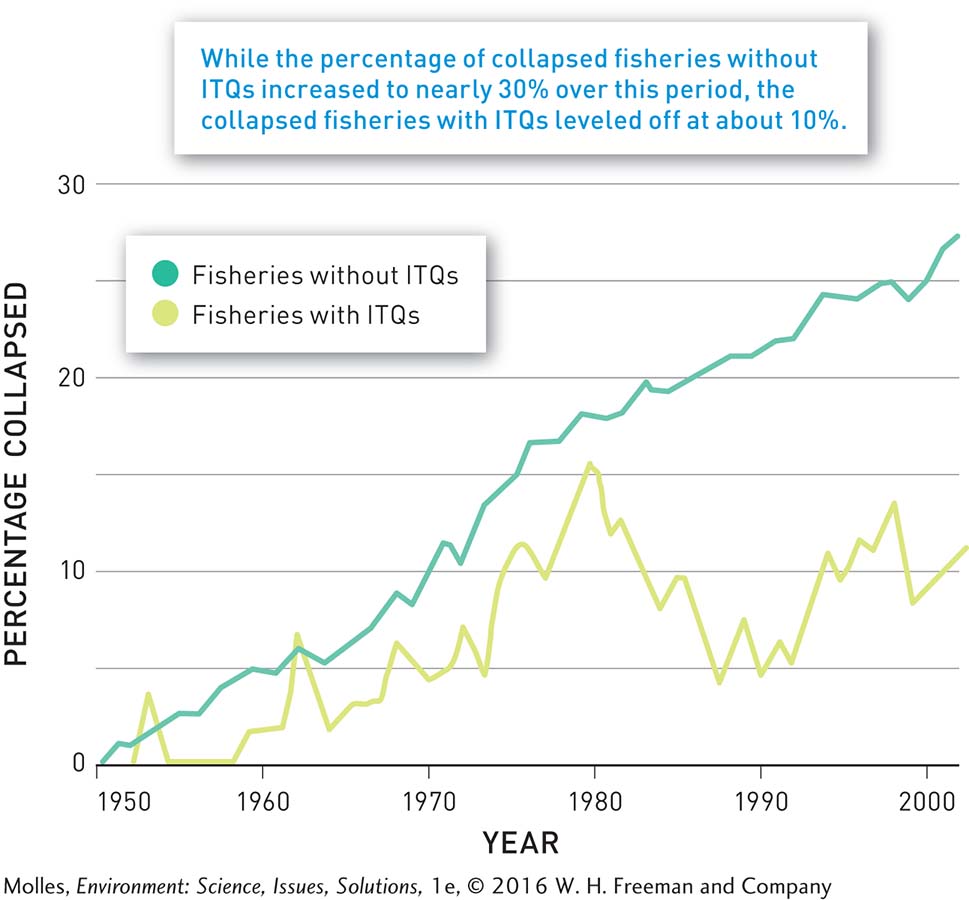

Catch shares have now been implemented in a number of U.S. fisheries, including groundfish, such as cod in the Northeast. A study of more than 11,000 fisheries showed that implementation of fishing quotas halts, and may even reverse, the global trend toward fisheries collapse (Figure 8.24).

An indirect benefit of rights-

Atlantic Cod Recovery

Twenty years after the collapse of the cod fishery in New England and eastern Canada, the stock has still not recovered. But there are signs that the ecosystem is returning to a more stable state. The plankton-

Think About It

What are the implications of the observation that collapsed fish or whale populations have commonly recovered after harvest has been reduced or eliminated, whereas others have failed to recover?

Establishing individual transferable quotas (ITQs) has seemed to put many fisheries on a path to sustainability. Why?