HOW DO WE KNOW?

FIG. 15.12

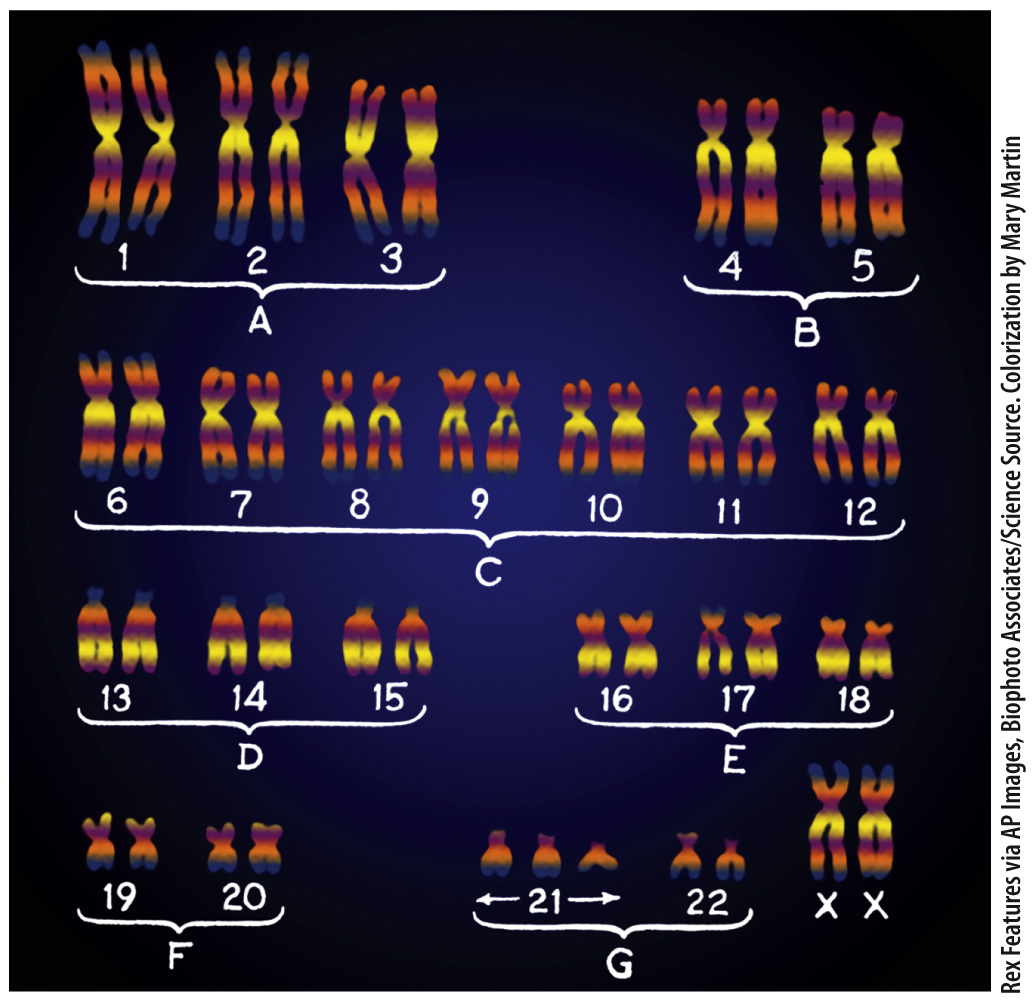

What is the genetic basis of Down syndrome?

BACKGROUND The detailed images of cells and chromosomes available today are produced by microscopic and imaging techniques not available during most of the history of genetics and cell biology. Techniques for observing human chromosomes were originally so unreliable that the correct number of human chromosomes was firmly established only in the mid-

HYPOTHESIS Down syndrome is associated with extra or missing chromosomes.

EXPERIMENT The chromosomes of five boys and four girls with Down syndrome were studied. A small patch of skin was taken from each child and placed in growth medium. In this medium, fibroblast cells, which synthesize the extracellular matrix that provides the structural framework of the skin, readily undergo DNA synthesis and divide. After allowing cellular growth and division, the fibroblast cells were prepared in a way that allowed the researchers to count the number of chromosomes under a microscope.

RESULTS Chromosomes were counted in 103 cells, yielding counts of 46 chromosomes (10 cells), 47 chromosomes (84 cells), and 48 chromosomes (9 cells). For each cell examined, the researchers noted whether the count was “doubtful” or “absolutely certain.” The researchers marked cells as “doubtful” if the chromosomes or nuclei were not well separated from one another. They encountered 57 cells of which they felt “absolutely certain,” and in each of these they counted 47 chromosomes. The extra chromosome was always one of the smallest chromosomes in the set.

CONCLUSION The researchers concluded that Down syndrome is the result of a chromosomal abnormality, an extra copy of one of the smallest chromosomes. The discovery helped resolve many of the questions surrounding the genetics of Down syndrome.

FOLLOW-

SOURCE J. Lejeune, Gautier, M., and Turpin, R. 1959. “Premier exemple d’aberration autosomique humaine.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Sciences. 248:1721–