FIG. 48.14 Representative marine biomes.

Intertidal

The part of the neritic (shallow-

Coral reefs

Coral reefs form another neritic biome, indeed, the most diverse biome in the oceans. The best-

Pelagic realm

The pelagic realm—

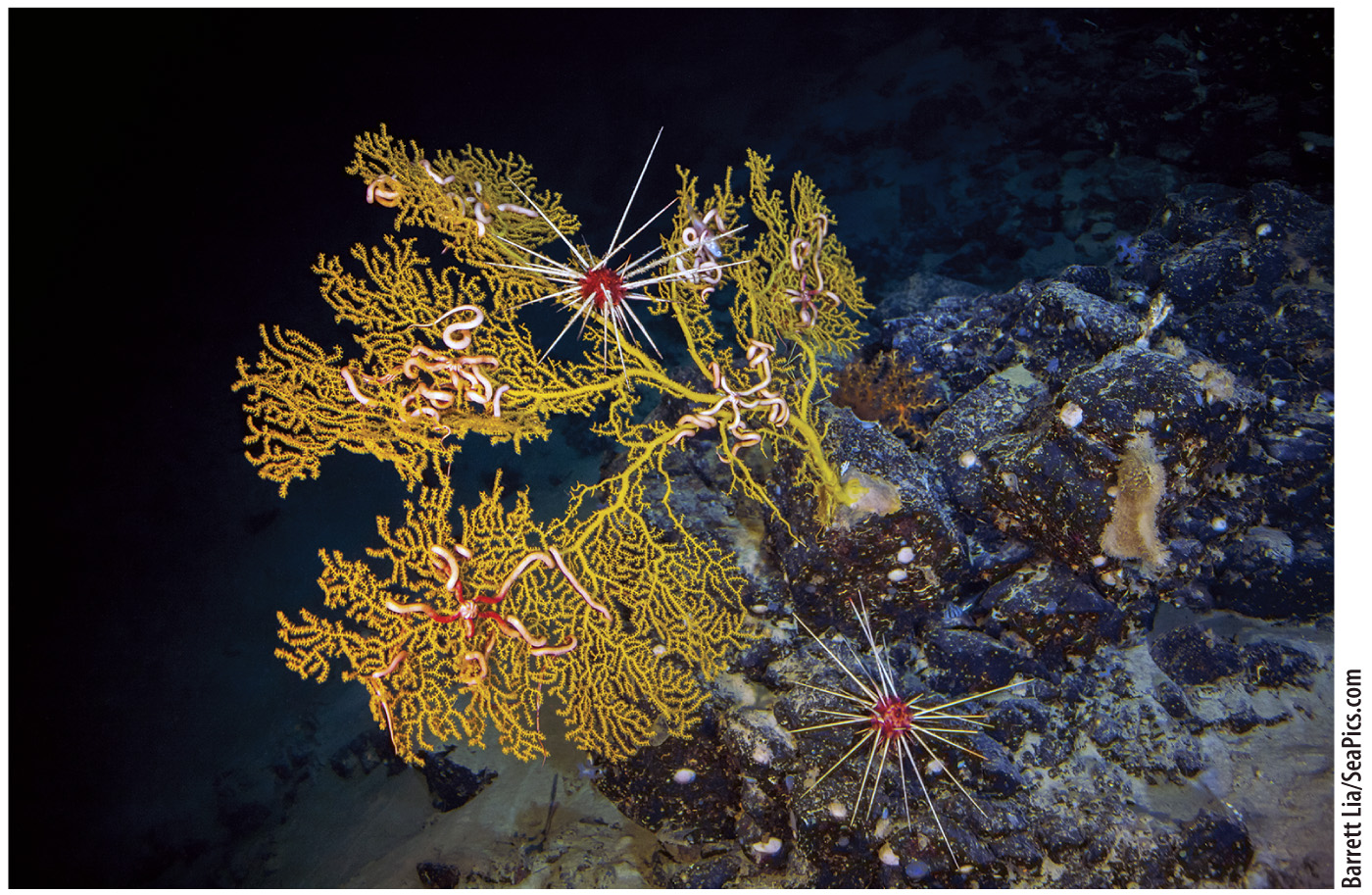

Deep Sea

Kilometers below the surface, deep seawaters are cold and dark, but they are not sterile. Sinking detritus supports sparse populations of animal consumers, as well as bacteria and archaeons that feed on organic particles. Despite their limited biomass, deep-