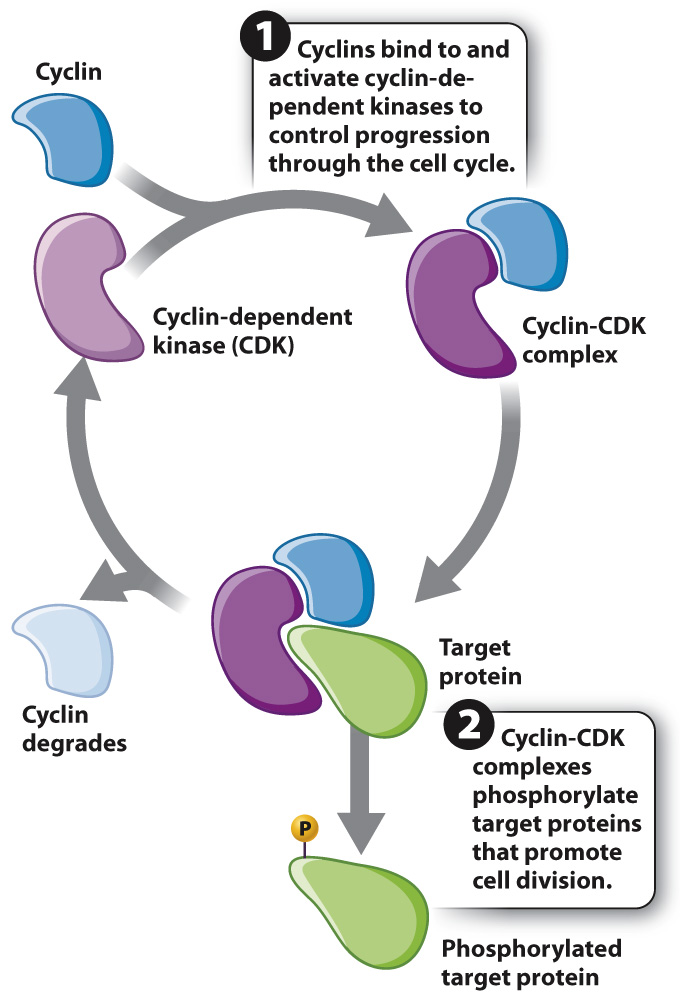

Protein phosphorylation controls passage through the cell cycle.

Early animal embryos, such as those of frogs and sea urchins, are useful models for studying cell cycle control because they are large and undergo many rapid mitotic cell divisions following fertilization. During these rapid cell divisions, mitosis and S phase alternate with virtually no G1 and G2 phases in between. Studies of animal embryos revealed two interesting patterns. First, as the cells undergo this rapid series of divisions, several proteins appear and disappear in a cyclical fashion. Researchers interpreted this observation to mean that these proteins might play a role in the control of the progression through the cell cycle. Second, several enzymes become active and inactive in cycles. These enzymes are kinases, proteins that phosphorylate other proteins (Chapter 9). The timing of kinase activity is delayed slightly relative to the appearance of the cyclical proteins.

These and many other observations led to the following view of cell cycle control: Proteins are synthesized that activate the kinases. These regulatory proteins are called cyclins because their levels rise and fall with each turn of the cell cycle. Once activated by cyclins, the kinases phosphorylate target proteins involved in promoting cell division (Fig. 11.14). These kinases, cyclin-

These cell cycle proteins, including cyclins and CDKs, are widely conserved across eukaryotes, reflecting their fundamental role in controlling cell cycle progression, and have been extensively studied in yeast, sea urchins, mice, and humans (Fig. 11.15).

HOW DO WE KNOW?

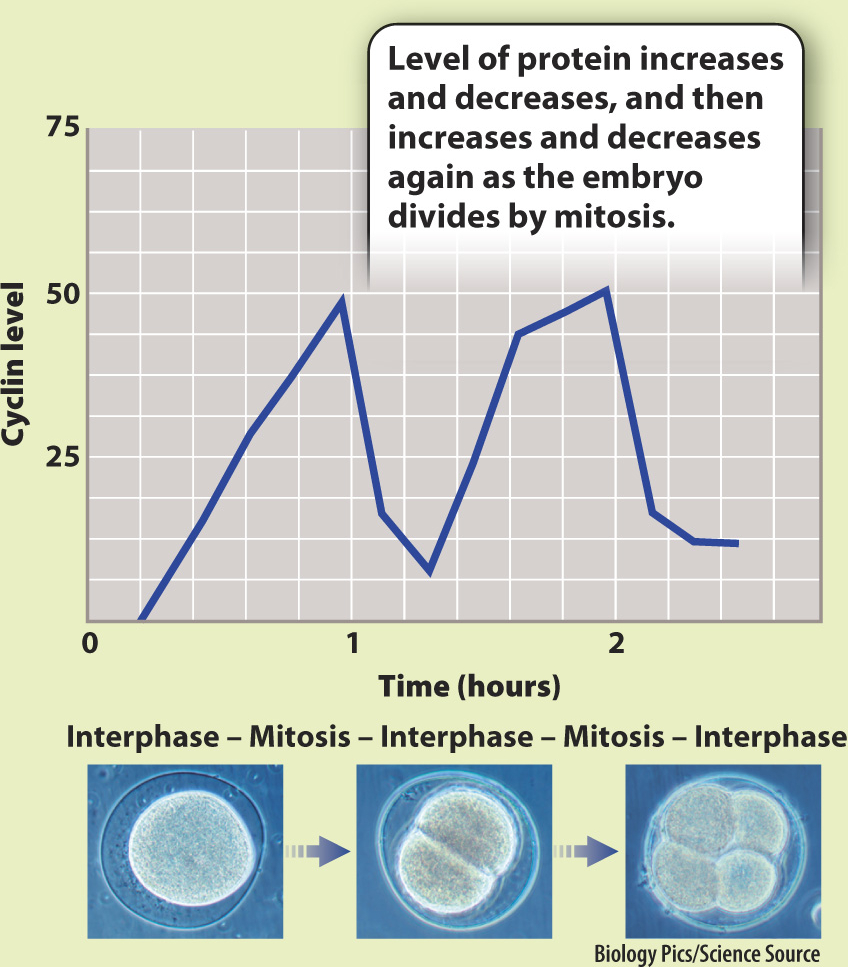

FIG. 11.15

How is progression through the cell cycle controlled?

BACKGROUND The cell cycle is characterized by cyclical changes in many components of the cell: Chromosomes condense and decondense, the mitotic spindle forms and breaks down, the nuclear envelope breaks down and re-

EXPERIMENT To better understand events in the cell cycle, English biochemist Tim Hunt and colleagues measured protein levels in sea urchin embryos as they divide rapidly by mitosis. He added radioactive methionine (an amino acid) to eggs, which became incorporated into any newly synthesized proteins. The eggs were then fertilized and allowed to develop. Samples of the rapidly dividing embryos were taken every 10 minutes and run on a gel to visualize the levels of different proteins.

RESULTS Most protein bands became darker as cell division proceeded, indicating more and more protein synthesis. However, the level of one protein band oscillated, increasing in intensity and then decreasing with each cell cycle, as shown in the graph.

CONCLUSION Hunt and colleagues called this new protein “cyclin.” Although they did not know its function, its fluctuating level suggested it might play a role in the control of the cell cycle. However, more work was needed to figure out if cyclins actually cause progression through the cell cycle or whether their levels oscillate in response to progression through the cell cycle.

FOLLOW-

SOURCE T. Evans et al. 1983. “Cyclin: A Protein Specified by Maternal mRNA in Sea Urchin Eggs That Is Destroyed at Each Cleavage Division.” Cell 33:389–