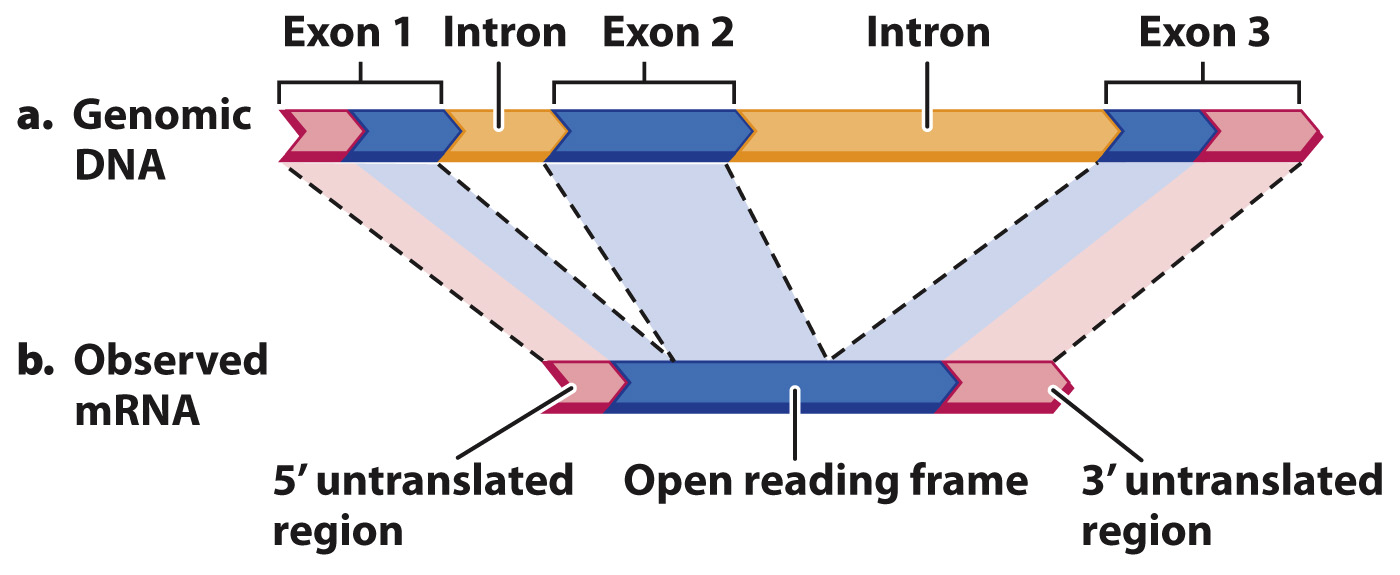

Comparison of genomic DNA with messenger RNA reveals the intron–exon structure of genes.

In annotating an entire genome, researchers typically make use of information outside the genome sequence itself. This information may include sequences of messenger RNA molecules that are isolated from various tissues or various stages of development of the organism. Recall from Chapter 3 that messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules undergo processing and are therefore usually simpler than the DNA sequences from which they are transcribed—

One aspect of genome annotation is the determination of which portions of the genome sequence correspond to sequences in mRNA transcripts. An example is shown in Fig. 13.5, which compares the DNA and mRNA for the beta (β) chain of hemoglobin, the oxygen-