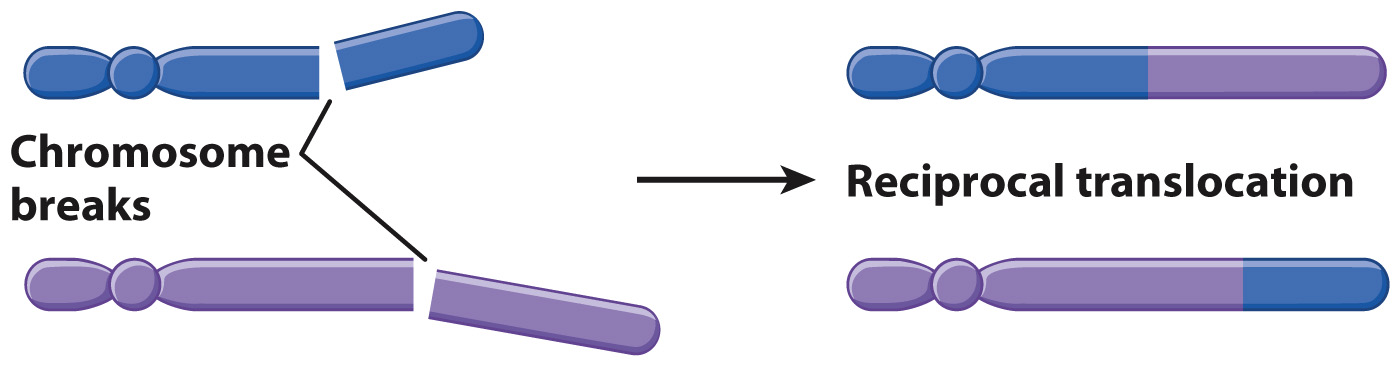

A reciprocal translocation joins segments from nonhomologous chromosomes.

A reciprocal translocation (Fig. 14.15) occurs when two different (nonhomologous) chromosomes undergo an exchange of parts. In the formation of a reciprocal translocation, both chromosomes are broken and the terminal segments are exchanged before the breaks are repaired. In large genomes, the breaks are likely to occur in noncoding DNA, so the breaks themselves do not usually disrupt gene function.

Since reciprocal translocations change only the arrangement of genes and not their number, most reciprocal translocations do not affect the survival of organisms. Proper gene dosage requires the presence of both parts of the reciprocal translocation, however, as well as one copy of each of the normal homologous chromosomes. Problems can arise in meiosis because both chromosomes involved in the reciprocal translocation may not move together into the same daughter cells, resulting in gametes with only one part of the reciprocal translocation. This inequality does upset gene dosage, because these gametes have extra copies of genes in one of the chromosomes and are missing copies of genes in the other. In the next chapter, we will see that such abnormalities are observed in a significant number of human embryos.