For individual nucleotides, mutation is a rare event.

We’ll see later in this chapter that there are several different types of mutation, but the most common mutation is the substitution of one nucleotide pair for a different nucleotide pair. Nucleotide-

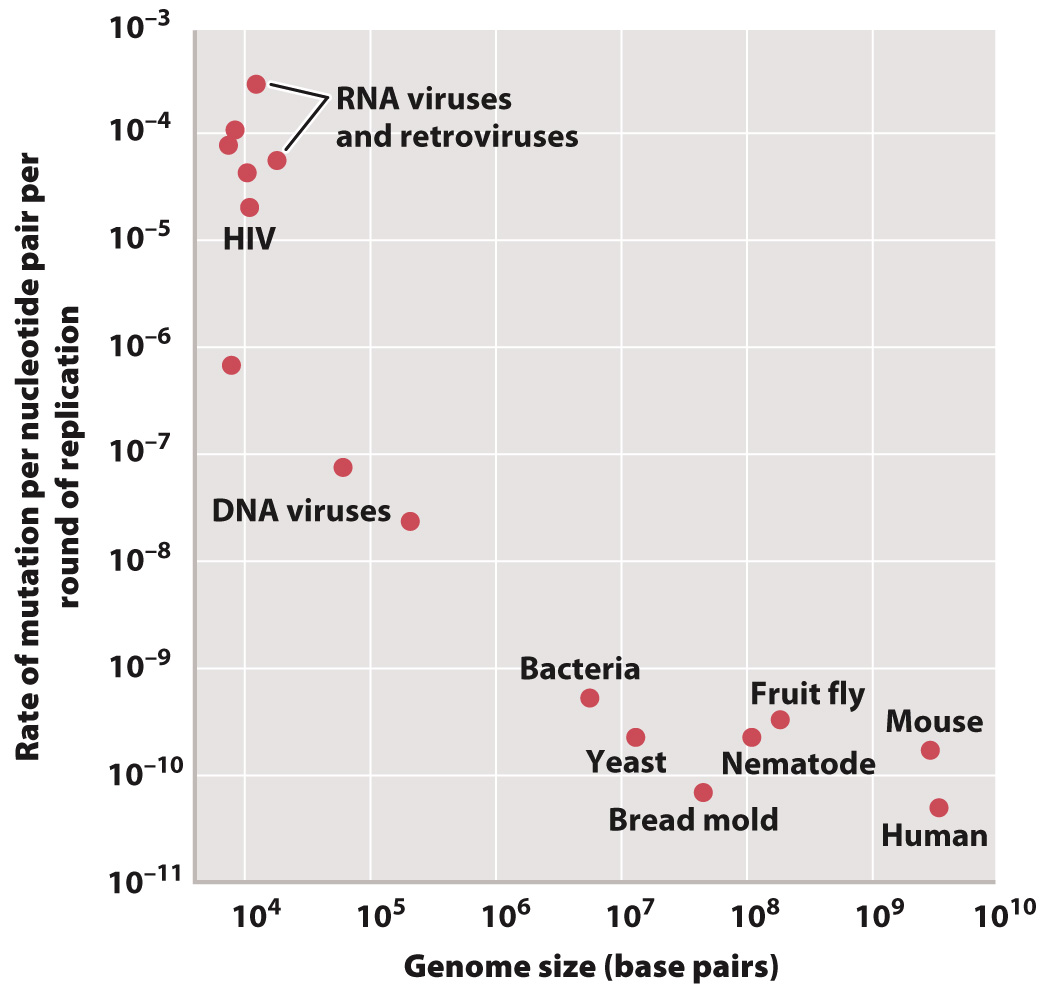

The highest rates of mutation per nucleotide per replication are found among RNA viruses and retroviruses, including HIV. Lower rates occur in DNA viruses, and even lower rates in unicellular organisms such as bacteria and yeast. The rates of mutation per nucleotide per DNA replication are nearly the same for all multicellular animals, including mice and humans.

Mutation rates vary over a large range for a number of reasons. RNA viruses and retroviruses have a relatively high rate of mutation because RNA is a less stable molecule than DNA, but more importantly because the replication of these genomes lacks a proofreading function. For the other genomes, the rate of mutation per nucleotide per DNA replication reflects differences in fidelity of replication and the efficiency of proofreading and other mechanisms of DNA repair.

For the cellular organisms plotted in Fig. 14.1, the average mutation rate is about 10–10, which means that, on average, only 1 nucleotide in every 10 billion is mistakenly substituted for another.

But averaging conceals many details. First, certain nucleotides are especially prone to mutation and can exhibit rates of mutation that are greater than the average by a factor of 10 or more. Sites in the genome that are especially mutable are called hotspots. Second, in some multicellular organisms, the rates of mutation differ between the sexes. In humans, for example, the rate of mutation is substantially greater in males than in females. Finally, the rates for the multicellular animals plotted in Fig. 14.1 depend on the type of cell: A distinction must be made between mutations that occur in germ cells (haploid gametes and the diploid cells that give rise to them) and mutations that occur in somatic cells (the other cells of the body). In mammals, the rate of mutation per nucleotide per replication is greater in somatic cells than in germ cells.