Segregation of the sex chromosomes predicts a 1:1 ratio of females to males.

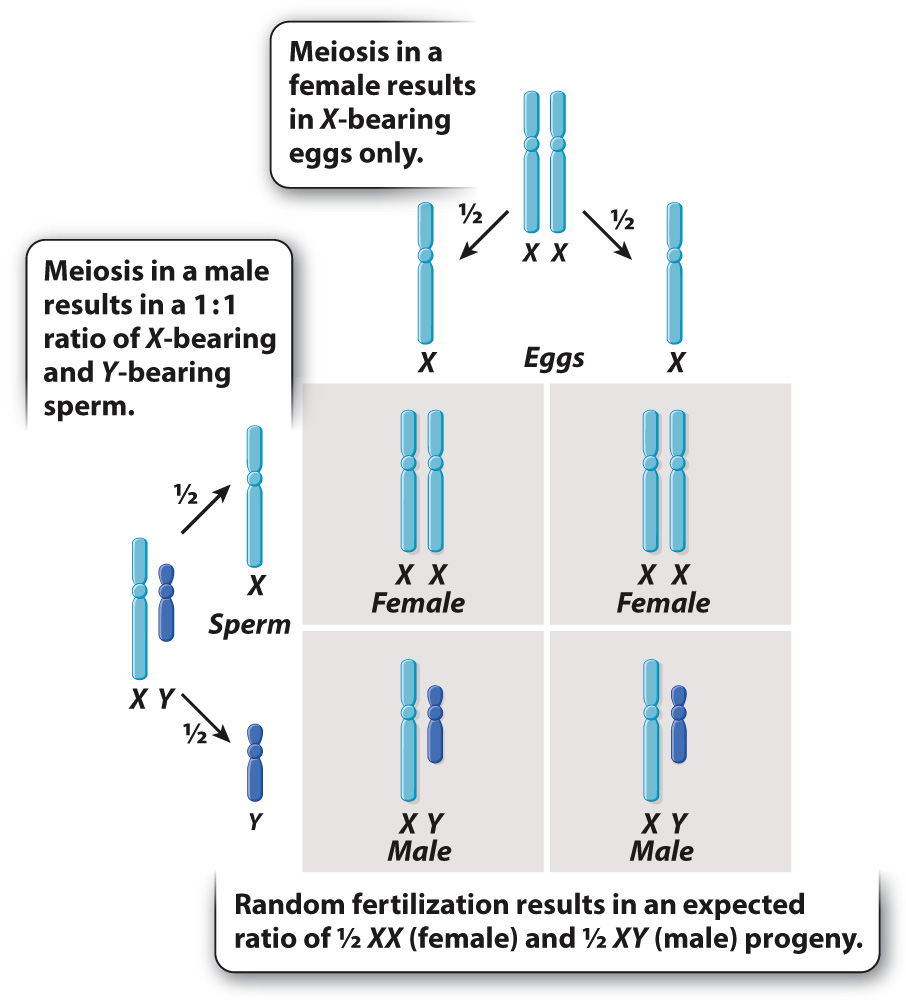

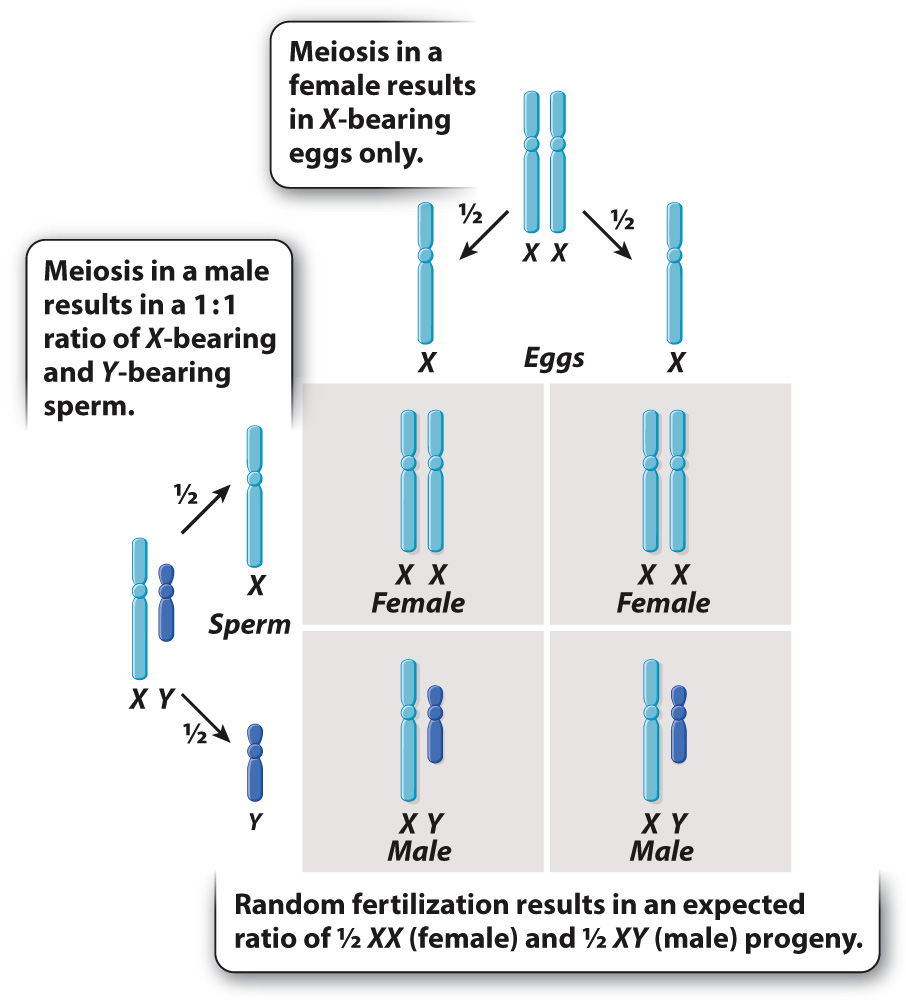

It is ironic that Mendel did not interpret sex as an inherited trait. If he had, he might have realized that sex itself provides one of the most convincing demonstrations of segregation. In human males, segregation of the X chromosome from the Y chromosome during anaphase I of meiosis results in half the sperm bearing an X chromosome and the other half bearing a Y chromosome (Fig. 17.2). Meiosis in human females results in eggs that each contains one X chromosome. With random fertilization, as shown in Fig. 17.2, half of the fertilized eggs are expected to be chromosomally XX (and therefore female) and half are expected to be chromosomally XY (and therefore male).

FIG. 17.2 Inheritance of the X and Y chromosomes. Segregation of the sex chromosomes in meiosis and random fertilization result in a 1:1 ratio of female:male embryos.

The expected ratio of 1:1 of females:males refers to the sex ratio at the time of conception. This is the primary sex ratio, and it is not easily observed because the earliest stages of human fertilization and development are inaccessible to large-scale study. What can be observed is the sex ratio at birth, called the secondary sex ratio, which differs among populations but usually shows a slight excess of males. In the United States, for example, the secondary sex ratio is approximately 100 females:105 males. The explanation seems to be that, for reasons that are not entirely understood, females are slightly less likely to survive from conception to birth. On the other hand, males are slightly less likely to survive from birth to reproductive maturity, and so, at the age of reproductive maturity, the sex ratio is very nearly 1:1. Male mortality continues to be greater than that of females throughout life, so that by age 85 and over, the sex ratio is about 100 females:50 males.

The sex of each birth appears to be random relative to previous births—that is, there do not seem to be tendencies for some families to have boys or for other ones to have girls. Many people are surprised by this fact, for they know of one or more large families consisting mostly of boys or mostly of girls. But the occasional family with children of predominantly one sex is expected simply by chance. When one occurs, its unusual sex distribution commands attention out of proportion to the actual numbers of such families. In short, families with unusual sex distributions are not more frequent than would be expected by chance.