X-linked inheritance was discovered through studies of male fruit flies with white eyes.

Morgan’s discovery of X-linked genes began when he noticed a white-eyed male in a bottle of fruit flies in which all the others had normal, or wild-type, red eyes. (The most common phenotype in a population is often called the wild type.) This was the first mutant he discovered, and finding it was a lucky break. As we saw in Chapter 16, most mutations are recessive, which means that when they occur their effect on the organism (the phenotype) is not observed because of the presence of the nonmutant gene in the homologous chromosome. Recall that the nonmutant form of a recessive mutant gene is dominant, and that the different forms of the gene are alleles.

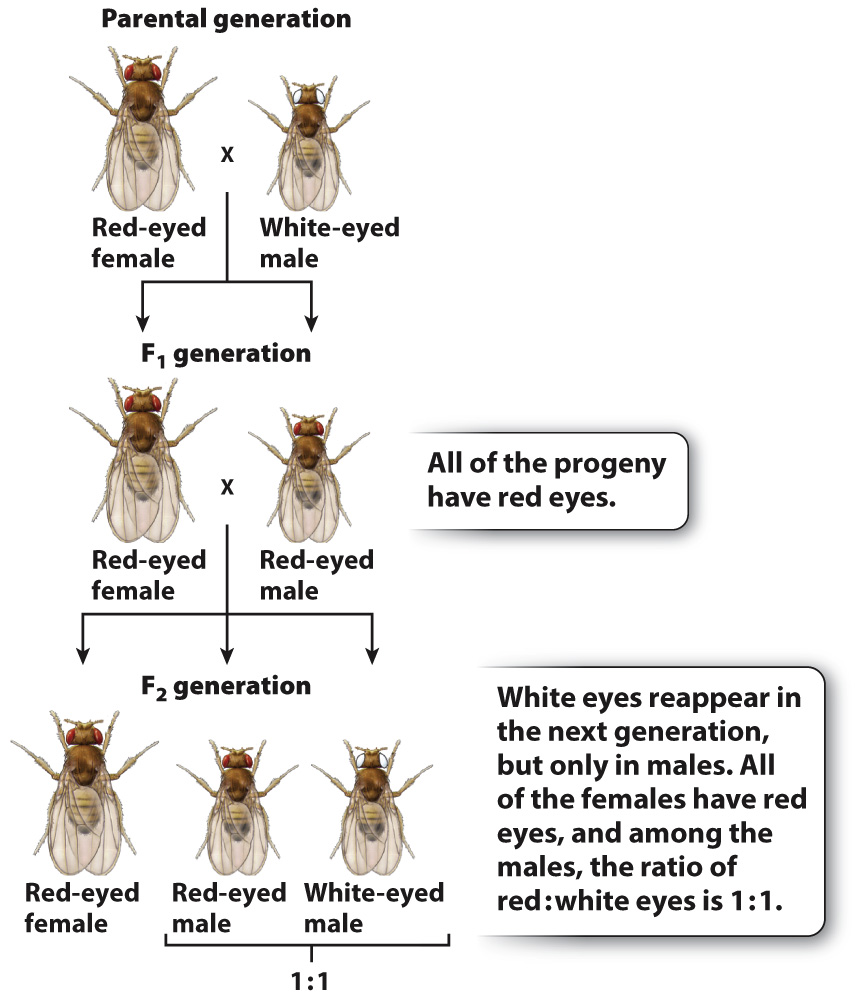

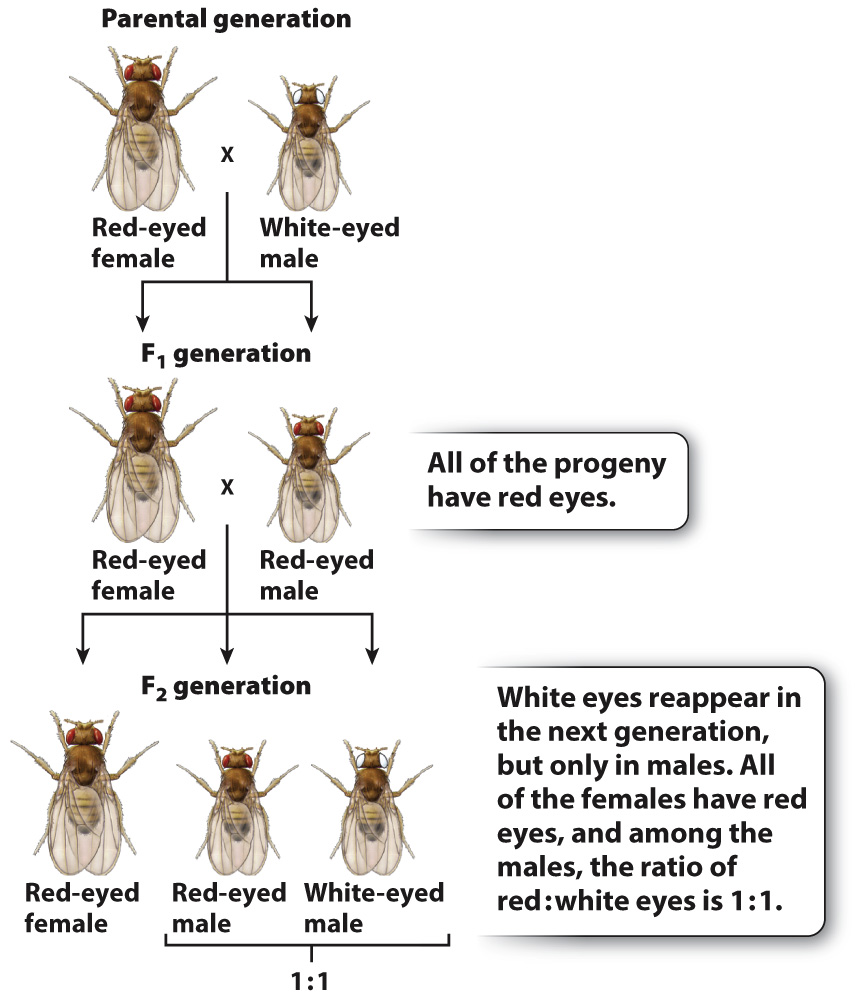

Morgan’s initial crosses are outlined in Fig. 17.3. In the first generation, he crossed the mutant white-eyed male with a wild-type red-eyed female. All of the progeny (F1) fruit flies had red eyes, as you would expect from a cross with any recessive mutation. Morgan then carried out matings between brothers and sisters among the F1 generation, and he found that the phenotype of white eyes reappeared among the progeny. This result, too, was expected. However, there was a surprise: Morgan observed that the white-eye phenotype was associated with the sex of the fly. In the F2 generation, all the white-eyed fruit flies were male, and the white-eyed males appeared along with red-eyed males in a ratio of 1:1. No females with white eyes were observed; all the females had red eyes.

FIG. 17.3 Morgan’s white-eyed fly. Morgan’s discovery of X-linked genes derived from his crosses of a white-eyed male in 1910.