Membranes define cells and spaces within cells.

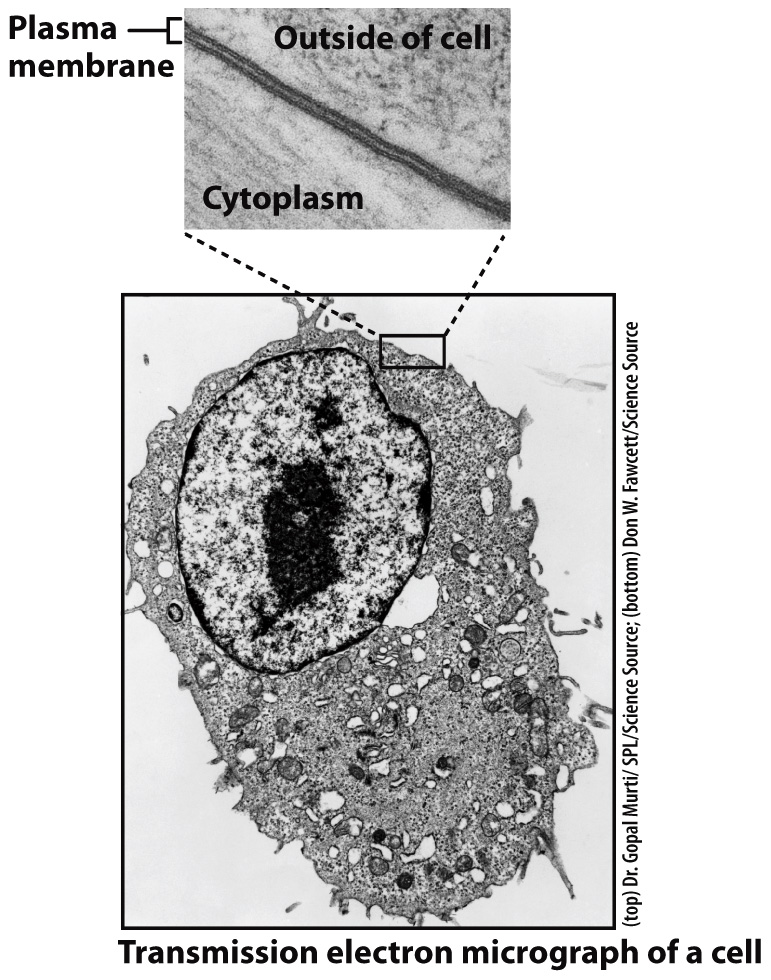

The second essential feature of all cells is a plasma membrane that separates the living material within the cell from the nonliving environment around it (Fig. 1.14). This boundary between inside and outside does not mean that cells are closed systems independent of the environment. On the contrary, there is an active and dynamic interplay between cells and their surroundings that is mediated by the plasma membrane. All cells require sustained contributions from their surroundings, both simple ions and the building blocks required to manufacture macromolecules. They also release waste products into the environment. As discussed more fully in Chapter 5, the plasma membrane controls the movement of materials into and out of the cell.

In addition to the plasma membrane, many cells have internal membranes that divide the cell into discrete compartments, each specialized for a particular function. A notable example is the nucleus, which houses the cell’s DNA. Like the plasma membrane, the nuclear membrane selectively controls movement of molecules into and out of it. As a result, the nucleus occupies a discrete space within the cell, separate from the space outside the nucleus, called the cytoplasm.

Not all cells have a nucleus. In fact, cells can be grouped into two broad classes depending on whether or not they have a nucleus. Cells without a nucleus are called prokaryotes, and cells with a nucleus are eukaryotes.

The first cells that emerged about 4 billion years ago were prokaryotic. Their descendants include the familiar bacteria, found today nearly everywhere that life can persist. Some prokaryotes live in peaceful coexistence with humans, inhabiting our gut and aiding digestion. Others cause disease—

Eukaryotes evolved much later, roughly 2 billion years ago, from prokaryotic ancestors. They include familiar groups such as animals, plants, and fungi, along with a wide diversity of single-

The terms “prokaryotes” and “eukaryotes” are useful in drawing attention to a fundamental distinction between these two groups of cells. However, today, biologists recognize three domains of life—