25.1 The Short-Term Carbon Cycle

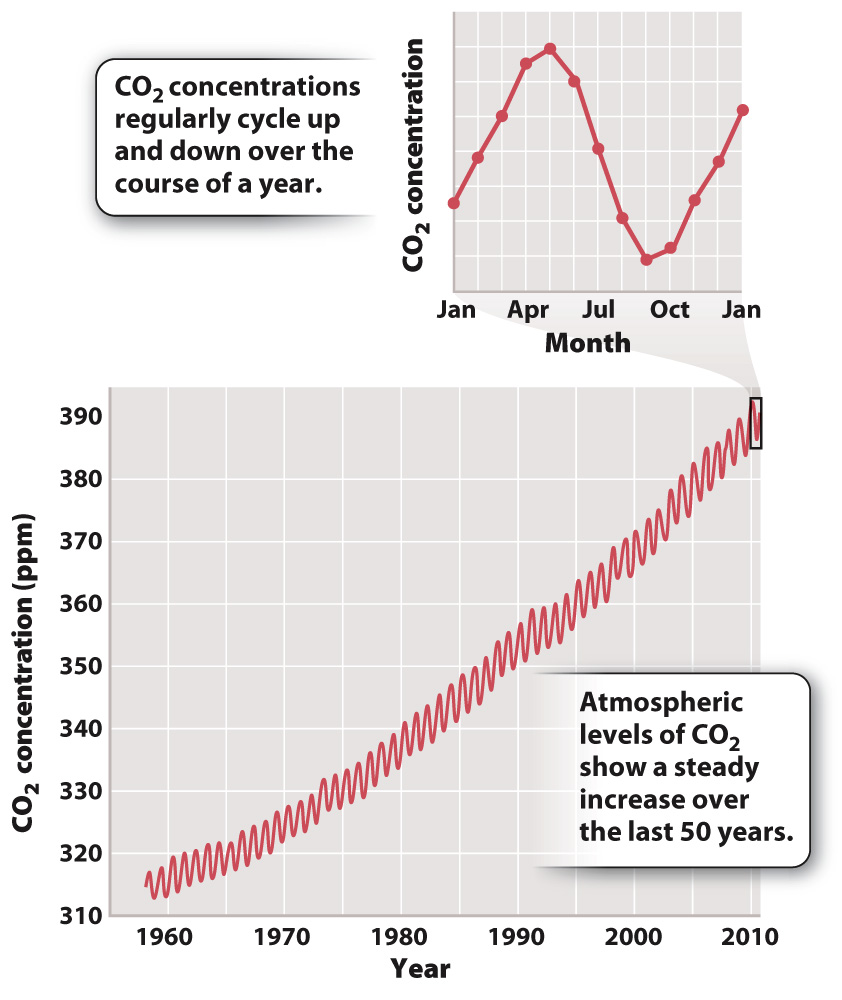

In 1958, American chemist Charles David Keeling began a novel program to monitor the atmosphere. At the time he began his study, scientists had only a vague notion of how carbon dioxide (CO2) behaves in air. Many thought that CO2 might vary unpredictably from time to time, and from place to place. Keeling decided to find out if in fact it did. From five towers set high on Mauna Loa in Hawaii, 3400 m above sea level, he sampled the atmosphere every hour and measured its composition with an infrared gas analyzer. Within the first few years of his project, a pattern of seasonal oscillation became apparent: CO2 concentration in the air reached its annual high point in spring and then declined by about 6 parts per million (ppm, by volume) to a minimum in early fall (Fig. 25.1). Such regular variation was unexpected: What could be causing it?

Perhaps the pattern was local. Airplane traffic to Hawaii peaked in winter, and maybe that was affecting the air around Mauna Loa. As measurements continued through a number of years, however, the pattern persisted, even as trends in air traffic changed. Moreover, monitoring stations in many other parts of the globe gave similar results. Knowing that the Mauna Loa measurements are representative of the atmosphere as a whole allows us to appreciate what an annual variation of 6 ppm really means. With calendar-

A second pattern is evident in Fig. 25.1. Summertime removal of CO2 from the atmosphere does not quite balance winter increase, with the result that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere on any given date is greater than it was a year earlier. Atmospheric CO2 levels have therefore increased steadily through the period of monitoring. For example, mean annual CO2 levels, about 315 ppm in 1958, reached 404 ppm by late April 2015. This is an increase of more than 25%, and there is no indication that the rise will slow or stop any time soon.

What causes atmospheric CO2 to vary through the year and over a timescale of decades? To answer this question, we need to ask what processes introduce CO2 into the atmosphere and what processes remove it. Carbon dioxide is added to the atmosphere by (1) geologic inputs, mainly from volcanoes and mid-