Bacterial phylogeny is a work in progress.

In Chapter 23, we introduced molecular phylogenies, in which gene sequences are compared to enable us to draw conclusions about evolutionary relatedness among populations in nature. Gene sequencing made it possible to test traditional bacterial groupings based on form and physiology. Some traditionally defined groups—

Molecular sequence comparisons bring enormous new possibilities to the study of prokaryotic diversity and evolution, but they introduce new problems as well. One set of problems arises because major groups of Bacteria and Archaea separated from one another billions of years ago. Inherited sequence similarities can be masked by continuing molecular evolution within groups. That is, specific nucleotides in gene sequences may change not once but multiple times through a long evolutionary history, erasing molecular features that were once the same because of inheritance from a common ancestor. Also, in some groups rates of sequence evolution appear to be higher than in others. As a result, these groups have especially divergent sequences and so may misleadingly fall toward the bottoms of phylogenetic trees.

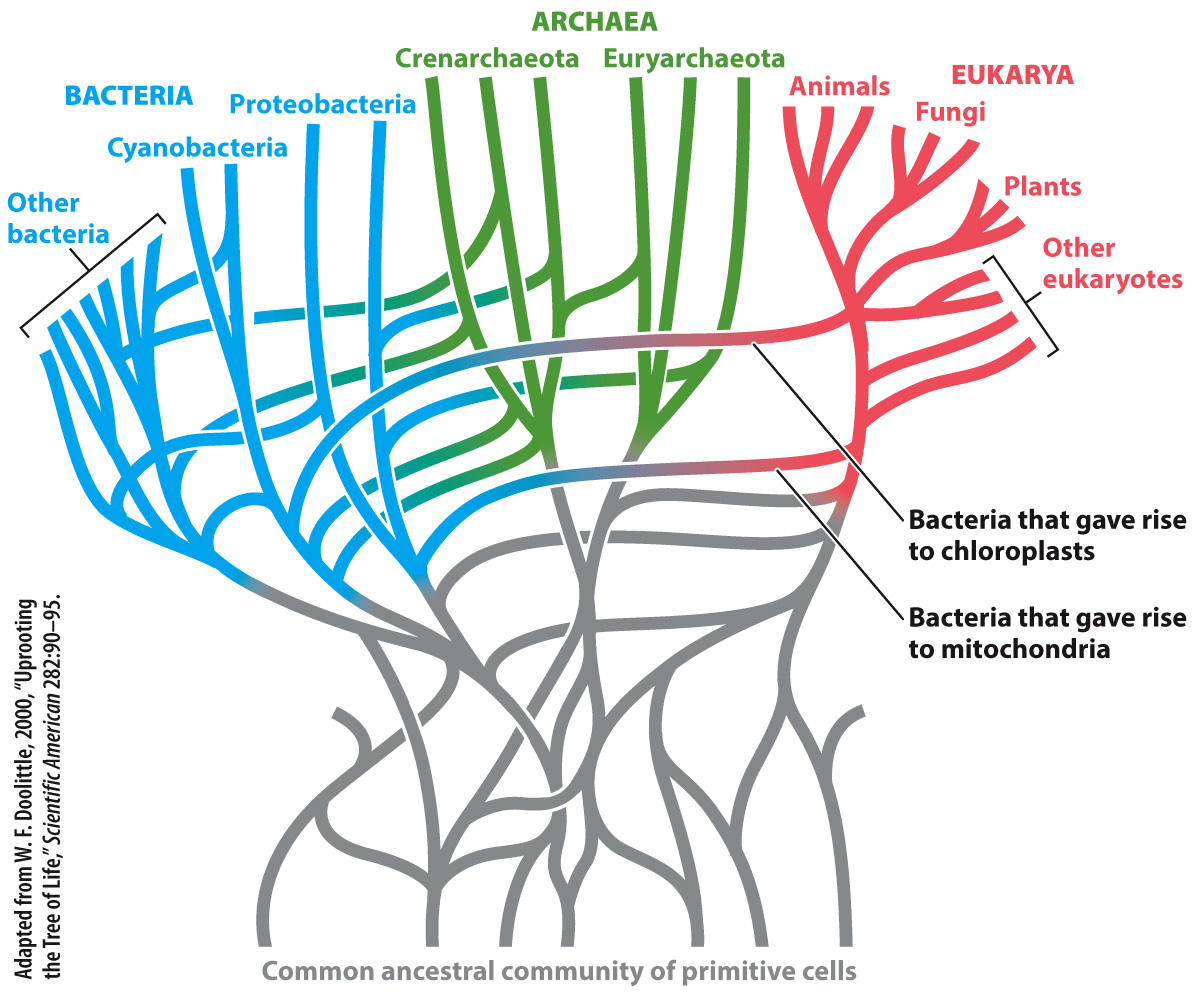

Another problem arises because of horizontal gene transfer. Phylogenies may falsely group distantly related bacteria because they contain genes passed on by conjugation, transformation, or transduction. Statistical analyses of complete bacterial genomes suggest that at least 85% of all genes in bacterial genomes have been transferred horizontally at least once. Such apparently rampant gene exchange might well doom attempts to build a bacterial tree of life, and some biologists argue that bacterial evolution is more properly depicted as a complex bush with many connecting branches (Fig. 26.14).

Other microbiologists are more optimistic. Small-

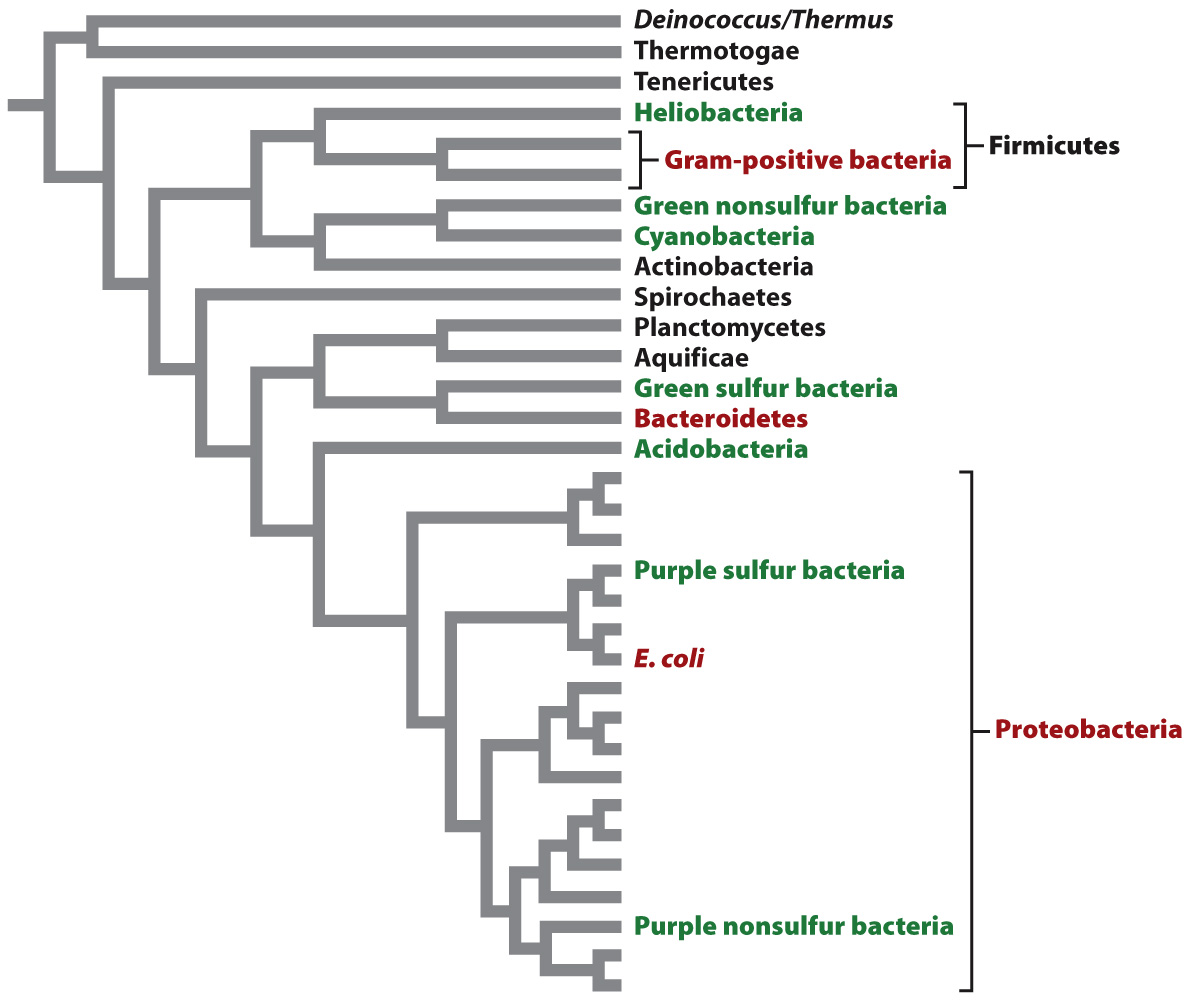

At present, molecular signatures have been extremely useful in identifying major groups of bacteria, but less clear in establishing branching order among these groups. About 50 major groups of bacteria (each one very roughly equivalent to a eukaryotic phylum) have been recognized. Nearly half of these groups cannot be cultured, but have been identified only by the cloning of genes from environmental samples. To support our discussion of bacterial diversity, we present a phylogeny based on comparisons of whole genomes in Fig. 26.15. As you examine this figure, remember that microbiologists continue to debate branching order on the bacterial tree.